New subscribers/followers: Thanks for signing up—I promise not to waste your time!

Older subscribers/followers: You too!

Reminder:

David’s Lists 2.0 does lists. I think ought to look like lists, so I don’t gum them up with backstory, bibliographica, personal history, dollops of wry commentary—all of which I save for the Notes.

Skipping the notes is1 . . .

A well-known writer got collared by a university student who asked, “Do you think I could be a writer?”

“Well,” the writer said, “I don’t know. . . . Do you like sentences?”

The writer could see the student’s amazement. Sentences? Do I like sentences? I am twenty years old and do I like sentences? If he had liked sentences, of course, he could begin, like a joyful painter I knew. I asked him how he came to be a painter. He said, “I liked the smell of paint.”

[Annie Dillard, The Writing Life]

Read about consciousness, and you’ll find this fiercely succinct statement:

Mind is what brain does.

To which, let’s add: Sentences are what writers do.

A human utterance. Then another, another, another.

But, also: a thing, a construction, an artifact with size and shape and duration and density and color/mood/tone. Some are show-offs, peacocks, some worker bees. Some come at us like big happy dogs, wet tongues awag. Some eye us slantwise, some tapdance, some minuet.

Today’s post is a little cache of sentences I admire, along with a few thoughts on how/why they work. [Some you may recognize from prior posts.]

1.

My first dose of Denis Johnson was the story “Work,” published in The New Yorker.2 Its severely hung-over narrator helps a friend salvage copper wire from a flood-ruined house. I felt weak, he tells us. Then:

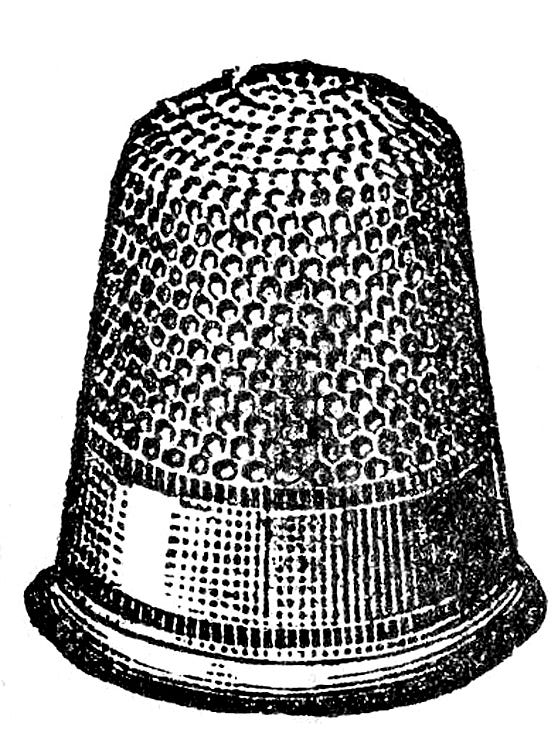

I had to vomit in the corner—just a thimbleful of gray bile.

The story (indeed, the book) is chock-a-block with voicey, dead-on sentences. Often (as here) the mundane is coupled with an out-of-the-blue word3 that manages not to feel labored. Consider how the moment plays without the last phrase: ordinary, vaguely squalid. Notice how deliciously out of place thimbleful is, the tension between it and bile. And yet, it’s exactly the correct unit of measurement under the circumstances, and this last detail is what shakes loose our empathy—who hasn’t found oneself in such a state?

2.

I’m a huge fan of stuff, the world’s physicality.4 Here are three clips I love for their accuracy, their noun-iness, their homely beauty:

Mrs. Antoinette Heft is at the Home Restaurant, placing frozen meat patties on waxed paper, pausing at times to clamp her fingers under her arms and press the sting from them.5

With oven mitts he delivers the pots to Leron, who dumps them steaming into the gurgling InSinkErator.6

He VisQueens off the doorway to the big room, begins dismantling the upstairs kitchen and groaty laminate-walled bath, then goes at the kitchen walls with sledge hammer, pry bar, and Sawzall. The old plaster is stone-hard and comes off the lath in lethal chunks, the frozen dribbles of undercoat clattering back inside the wall.7

3.

It’s easy to find caches of great opening sentences,8 so we’ll skip that. Once in a while, though, a work’s first line miraculously distills the entire story into a single statement.9

Here’s my favorite, from Ian McEwan’s 2007 novel, On Chesil Beach:

They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.

4.

There are great last sentences, too. The exit lines of The Sun Also Rises10, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn11, The Great Gatsby12, and a cadre of others are famous . . . but this morning I want to return to an observation from an earlier point, that a work’s smaller structures have their own beginning/middle/end, and use the same dramatic strategy of withholding the key image/thought/word until the last instant.

In the first example (from E. B. White’s essay, “Once More to the Lake”13), the narrator revisits, with his own son, the lake where he was brought as a boy. The piece is infused with time’s passage, the turnover of generations. It ends:

When the others went swimming, my son said he was going in, too. He pulled his dripping trunks from the line where they had hung all through the shower and wrung them out. Languidly, and with no thought of going in, I watched him, his hard little body, skinny and bare, saw him wince slightly as he pulled up around his vitals the small, soggy, icy garment. As he buckled the swollen belt, suddenly my groin felt the chill of death.

The other ends a John Updike short story, “Deaths of Distant Friends” (the friends are a gaudily attired ex-golf partner, a Back Bay doyenne who befriended the narrator and his wife when they were freshly married, and a golden retriever named Canute). It’s a passage only Updike could’ve written—especially the last sentence’s rhythm, its meticulous punctuation:

In truth—how terrible to acknowledge—all three of these deaths make me happy, in a way. Witnesses to my disgrace are being removed. The world is growing lighter. Eventually there will be none to remember me as I was in those embarrassing, disarrayed years when I scuttled without a shell, between houses and wives, a snake between skins, a monster of selfishness, my grotesque needs naked and pink, my social presence beggarly and vulnerable. The deaths of others carry us off bit by bit, until there will be nothing left; and this, too, will be, in a way, a mercy.14

5.

A few novels come at us like avalanches—Lucy Ellman’s Ducks, Newburyport (2019), for instance15 . . . big breathless artifacts.16 But, instead, let’s consider big sentences in otherwise “regular” fiction. [You’ll find a wealth of them here.17]

What are they for, how do they do what they do?

They often gain their mass by listing things, which amps up a passage’s mood of expansiveness or variety or exuberance, even greed or insistence or overload—this, this, this, this, this— They have the space to be rhythmic, to do patterns-with-variations, using repeated phrases/images.

They’re a kind of showing off—unless you’re a rare bird, a whole book’s worth of showing off is exceedingly tiresome. Instead, think of them as solos, sudden eruptions of over-the-top-ness, a bit o’ the old razzle-dazzle. For aminute or two, you get to be David Gilmour.

Here’s one that erupted in Philip Roth’s American Pastoral (1997)18 [this one is actually made of several sentences]:

From over the door of the house, the pediment was gone, ripped out; the cornices had been ripped out too, carefully stolen and taken away to be sold in some New York antiques store. All over Newark, the oldest buildings were missing ornamental stone cornices—cornices from as high up as four stories plucked off in broad daylight with a cherry picker, with a hundred-thousand-dollar piece of equipment; but the cop is asleep or paid off and nobody stops whoever it is, from whatever agency that has a cherry picker, who is making a little cash on the side. The turkey frieze that ran around the old Essex produce market on Washington and Linden, the frieze with the terra-cotta turkeys and the huge cornucopias overflowing with fruit—stolen. . . . Aluminum drainpipes even from occupied buildings, from standing buildings—stolen. Gutters, leaders, drainpipes—stolen. Everything was gone that anybody could get to. Just reach up and take it. Copper tubing in boarded-up factories, pull it out and sell it. Anyplace where the windows are gone and boarded up tells people immediately, “Come in and strip it. Whatever’s left, strip it, steal it, sell it.” Stripping stuff—that’s the food chain.19

6.

No extra words, I used to tell students.

Good advice . . . but it involves two separate aspects of writing. The first, line editing, is a skill you acquire (for starters, you have to learn which words are the extra ones). For me, it’s by far the easiest part of writing well. [More on this here.20]

The other is voice—the way the mind of the story expresses itself. Some voices ramble, side-trip, gush, share profusely or rattle on to the point of pathology. Some are the other way, squeaky tight. Maybe they’re more reserved by nature, or fearful of disclosing too much, or prefer sticking to the point—or whatever.

In Birth Year Project: 1944 (note 18), I cited Joyce Cary’s novel, The Horse’s Mouth. Gully’s an aging artist/scoundrel in pre-war London—we meet him as he’s emerging from the slammer, returning to his ramshackle boat on the Thames. Here’s that sample of Gully’s narration, again:

No one in the bar but Coker. “Is it Willy again?” I asked her. Willy was Coker’s young man. A warehouse clerk shaped like a soda water bottle. Face like a bird. All eyes and beak. Bass in the choir. Glider club. Sporty boy. A sparrowhawk. Terror to the girls. Coker was church, teetotal and no smoke. Willy her only weakness.

No patience for the formality of proper sentences. Twitchy. Fragmentary. Quick.

Another writer known for this is James Ellroy, Over the years, his style has grown more and more this way—staccato, telegraphic, tough-guy prose. I’ve read only one of his, American Tabloid, (1995). [You can read about Ellroy and his prose style all over the internet21.]

In examples like those, the whole work embodies the voice.

But sometimes you find an especially terse/compact sentence in a passage that otherwise reads “straight.” It hits you the way “Jesus wept” does. Especially useful after a really long sentence.

Anyway, I now have the pleasure of showing you one from W. G. Sebald’s travelogue/novel/meditation on mortality, The Rings of Saturn (1995). The book begins with a look at the life of Thomas Browne [1605-1682, physician, author of Urn Burial]. For Browne, Sebald writes, there was no antidote . . . against the opium of time. Unfolding this idea, a few sentences later, he says:

Indeed, old families last not three oaks.

The sleek dive from the high board, no splash. Hall of Fame.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rings_of_Saturn

Notes: Hey, good to see you down here!

If you read these posts at Substack (as opposed to via your email) and (ideally) read them on your laptop, the notes will pop up when you hover the cursor—no scrolling up and down. But, either way, my fond encouragement: Grant yourself time for the notes.

"Work”: The New Yorker (November 14, 1988), then in the collection/novel, Jesus’ Son (1992).

Out-of-the-blue word: A comment by Sting I heard the other day: If I don’t hear something that surprises me in the first eight seconds,I stop listening.

"Stuff”: This was the title of a piece I wrote for Poets and Writers Magazine (September/October 2002), later reprinted in The Practical Writer, Therese Eiben and Mary Gannon, eds. (2004).

Mrs. Antoinette Heft: From the title story of Ron Hansen’s collection, Nebraska (1989). [You should also read “Wickedness” from that book.]

InSinkErator: Last Night at the Lobster, Stewart O’Nan (2007).

VisQueen: This is mine, from the story “Zebras” in Crazy Horse (lit mag), Fall 2015.

Opening sentences: In her eminently useful handbooks, Book Lust and More Book Lust, Seattle librarian Nancy Pearl cites some of her faves, including this lovely tease from Rhian Ellis’s novel, After Life (2000):

First I had to get his body into the boat.

[Can I tell you about Rhian? She arrived at an insight many of never quite do: that, for her, writing books wasn’t (as we say at my house) couping the moutarde; she went back to school and became a psychiatric nurse. Brava!]

Single statement: You can think of this as a distillate or reduction (in the cooking sense) to its most concentrated/essential state. Yet, you can also picture this from the opposite end, as an ur-particle—the universe a nano-second before the Big Bang.

Classical art theory holds that great works have claritas [brightness, clarity], veritas [truthfulness], and unitas [unity, wholeness]. When I said, a few posts ago, Wherever you look in Picasso’s Guernica, you find Picasso’s Guernica], I meant that every bit of it comes from the same source, Guernica’s ur-particle exploded into being . . . and, to follow this metaphor out another beat: as with the Big Bang, this new entity doesn’t fill out existing space, but creates space as it comes [hard to picture, I know, but think of Sharpie dots on a flaccid balloon—when you blow it up they get farther apart because the space between them was created]. Anyway, this is how I conceptualize the quality of unitas in art.

You don’t need to get into theory, of course—you just need to be engaged with the writing so that it doesn’t just rush past you. Anyway, after you’ve read a book, go back and look at its first sentence and ask the question, Why this sentence first?

The Sun Also Rises (1926):

“Yes,” I said. “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885):

But I reckon I got to light out for the Territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she’s going to adopt me and sivilize me and I can’t stand it. I been there before.

The Great Gatsby (1925):

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

"Once More to the Lake”: Published in Harper’s Magazine (1941) and in Essays of E. B. White (1977). White was a superb observer of life and craftsman of sentences, a long-time New Yorker editor, and writer of kid-lit classics, Charlotte’s Web (1952) and others.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._B._White

We have a slew of great essayists these days, especially women—Leslie Jamison, Meghan Daum, Maggie Nelson, Roxane Gay, and a host of others. We often read fiction from White’s era, but much less often, I think, nonfiction, personal essay. When I was a young writer I found White’s essays a terrific model. Try some, OK?

Oh, and while I’m at it: You may know one of White’s contemporaries at The New Yorker, Joseph Mitchell—Up in the Old Hotel (1992) and the slim volume, Old Mr. Flood (1948), which I treasure beyond words [I have a somewhat bedraggled first edition a friend gave my father in days of yore]. But I want you to know another of their contemporaries, Berton Roueché, whose NYer pieces [“Annals of Medicine”] are in several collections, the one I love being Eleven Blue Men (1953). Why were the men blue? You’ll have to go see.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleven_Blue_Men

https://archive.org/details/oldmrflood0000jose/page/n7/mode/2up

“Deaths . . .”: In Trust Me: Short Stories (1987).

Ducks: From Wiki:

The novel is written in the stream of consciousness narrative style, and consists of a single long sentence, with brief clauses that start with the phrase "the fact that" more than 19,000 times. The book runs over 1000 pages. It won the 2019 Goldsmiths Prize and was shortlisted for the 2019 Booker Prize..

Big, breathless:

https://theglocalexperience.wordpress.com/2018/07/15/awe-inspiring-one-sentence-novels-you-never-knew-existed/#:~:text=Awe%2DInspiring%20One%2DSentence%20Novels%20You%20Never%20Knew%20Existed,The%20Last%20Wolf%20by%20L%C3%A1szl%C3%B3%20Krasznahorkai%20(2009)%2C

Cache of long sentences:

https://thejohnfox.com/2021/08/65-long-sentences-in-literature/

Roth: I have really mixed feelings about Roth. I wish he’d written fewer novels; I wish he’d been less Borscht-Belty [not to mention misogynistic] . . . because when he was on, he was a real heavyweight. My favorite is The Plot Against America (2004) . . . Lindbergh beats FDR in 1940; anti-semitism, America-First-ism overtake the country—partially autobiographical. I also like his slender late novels. [Admission: I’ve never actually read Portnoy’s Complaint (1969).]

American Pastoral: Don’t have a copy in front of me . . . I seem to remember cutting some where the ellipsis is—thus, it was even longer.

Three other terrific examples I lack space for here:

The opening of Stuart Dybek’s short story, “We Didn’t” [in I Sailed With Magellan (2003)—a young couple’s serio-comic lament about thwarted sex.

The bravura 237-word opening paragraph of Patrick Süskind’s novel, Perfume (1976)—cataloging the pervasive stench of 18th-C. French life—study it for the power of listing and the repeating a key word throughout.

The opening of Faulkner’s story, “Golden Land."

Which words: An exercise I performed several times at the request of editors: Shorten a story by X-number of words/pages. In a full-length story, I found you can cut 1-2 pages (painlessly, in one sitting) by cutting however many words it takes to shrink each paragraph by a line. After that, it’s a matter of throwing stuff (words, phrases) overboard until the boat’s seaworthy. Your mindset does a one-eighty: OK, don’t really need this, or this, or this . . . oh and I can say this a lot faster . . . and so on.

Once I was asked to make a 32-page story a 22-page story; only after getting it down to maybe 26 pp. did I have to lose truly vital tissue. It was published, in a magazine, at 24 pp.; the version I later put in a book had a few bigger chunks restored, but was otherwise the 26-page iteration—in other words, it hadn’t really been a 32-page story, but a 26-page story wearing a fat suit.

Elroy:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Ellroy

http://therapsheet.blogspot.com/2016/01/my-ellrovian-journey.html

Oh, to love the fragrance of sentences! The vivid accuracy of Denis Johnson’s thimble.

Your idea that a great sentence “shakes loose our empathy,” is so spot on. Also that a story can go ahead and be a peacock for a moment with sentences that are vibrant and shimmery, and then drop back to the ground where the dirt and lost coins are. Thanks for another rich and lively post, DL!

Great post! So many examples! Thank you, David.