Birth Year Project:

You supply your birth year, I respond with a short list of books published that year—the popular/well-known titles first, then some books I'd recommend. If your year's already been done, I'll do an update. So far, we’ve done 17 years altogether, between 1944 and 1989.

Extra credit: You read one of the books (ideally one you're unfamiliar with), then tell me what you thought. If we get enough of these, I'll aggregate and post.

A note on 1944:

The Birth Year Project is mainly concerned with literary fiction, plus a few genre titles and nonfiction works that impact/reflect our culture/history/attitudes.

I skip over most mysteries, thrillers, straight horror, potboilers, books with Fabio on the cover (or unicorns), and so on. That said, as we know, some writers achieve excellence via genre pathways, often sci-fi/speculative lit—Ursula K. le Guin, Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, Octavia Butler, Emily St. John Mandel, Nnedi Okorafor, and a slew of younger writers.1

Of the twenty books in Birth Year Project 1944, only Anna Seghers’ Transit (drawn from her own experience) and John Hersey’s A Bell for Adano deal directly with WWII. Which leads to two thoughts: First, reading about Seghers, I’m still taken aback (though I shouldn’t be) at how many significant European writers (not to mention South American, African, Middle-Eastern, etc.) I’ve never so much as heard of. Why is this? Simple cultural myopia, the love of the new, the overwhelming volume of the world’s writing, the unrelenting power of time to suck everything into the oubliette? All of the above? OK, too big a subject for here.

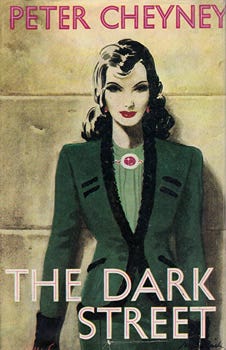

But the other (less inscrutable) thought: While the war would generate a tidal wave of literature (or waves—they’re still coming), most literary works took time and less fraught circumstances to be written.2 3 It’s the genre writing from the war years that depicts the war. The (irresistible) book cover atop today’s post is from a mystery. A few others: Rex Stout’s Not Quite Dead Enough, Cecil Street’s Death Invades the Meeting, Christianna Brand’s Green For Danger . . .

Best-Sellers/Well-Known Books:

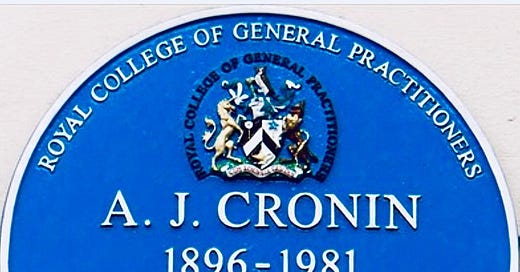

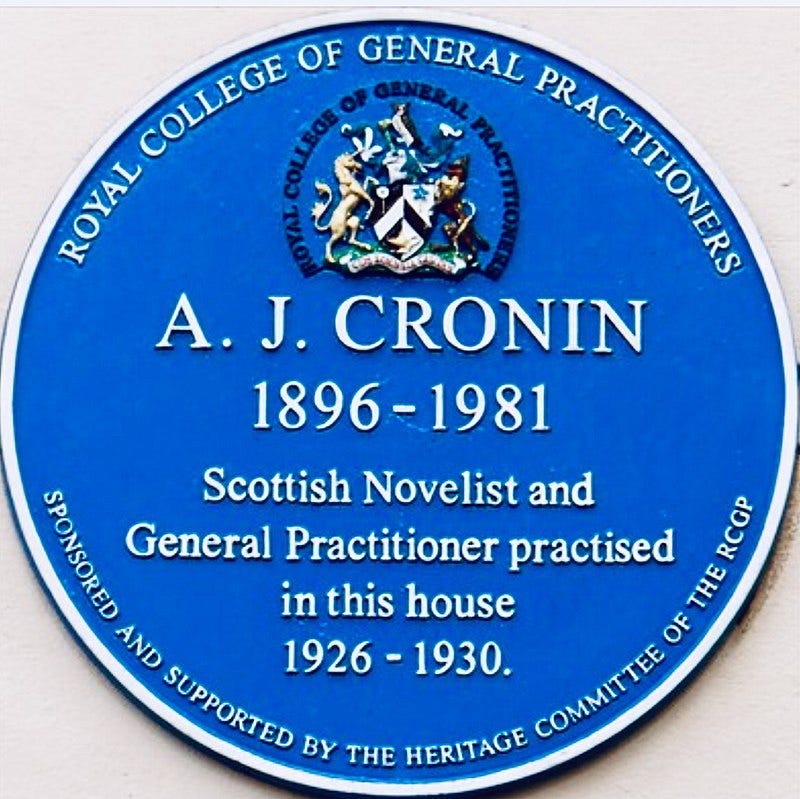

The Green Years, A. J. Cronin4

A Bell for Adano, John Hersey5

The Razor's Edge, W. Somerset Maugham

Strange Fruit, Lillian Smith6

Forever Amber, Kathleen Winsor7

Five Works of World Literature:

Balyakalasakhi, Vaikom Muhammad Basheer8 [India]

Ficciones, Jorge Luis Borges 9 [Argentina]

Gigi, Colette10 [France]

The Dwarf, Pär Lagerkvist11 [Sweden]

Transit, Anna Seghers12 [Germany]

Three Plays:

Harvey, Mary Chase13

No Exit, Jean-Paul Sartre

The Glass Menagerie, Tennessee Williams

Special Mention:

The Shrimp and the Anemone, L.P. Hartley14

The Lost Weekend, Charles R. Jackson15

Anna and the King of Siam, Margaret Landon16

The Case of Mrs. Wingate, Oscar Micheaux 17

My List:

The Horse’s Mouth, Joyce Cary (1944)18

The Razor’s Edge, W. Somerset Maugham (1944)19

Winter Wheat, Mildred Walker (1944)20

Interesting that these are all women writers. The other Birth Year Project I did this week (1959) was overwhelmingly male; 1944 is a bit less lopsided: 7 women, 13 men.

These days, my own reading skews female—last year (2023): 30 women, 23 men; the year before: 39 women, 36 men. Literary writing has always had strong female voices, even before the time of the Brontës, Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot, Lousia May Alcott (and many less-familiar names), there were Jane Austen and Mary Shelley, and their contemporaries, such as Maria Edgeworth [check out Castle Rackrent (1800)], and before them a cadre of Gothic writers (Ann Radcliffe, Eliza Parsons), the wildly popular Fanny Burney [Evelina (1778), Cecilia (1782)], and Charlotte Lennox [The Female Quixote (1752)], and before them Margaret Cavendish [The Blazing World (1666), Aphra Behn, and others.

What’s my point—or points? That despite the machinery of publication and the machinery of canon-making, women writing in English were not completely locked out. But that it’s only lately that the mid-20th century obsession with the Big Masculine Novel has waned as women have surged into the book business, become agents, editors, publishers, booksellers, reviewers and critics, and so on. That in a year as recent as 1959 (I know, ancient history for you, but the year I turned eleven), I ended up with Shirley Jackson and 34 men, because the books women published that year were virtually all mysteries or pulps or weaker novels by more literary writers.

Norman Mailer’s, The Naked and the Dead (1948), is usually cited as the first novel by a participant/soldier in the war—but this may mean “in English.”

Just as The Depression, the dominant subject of 1930s, still occupied some 1940s writers. But the war brought a radical change of national mood. Writing centered on poverty, class struggle, socialism, etc. was suddenly out of favor with American publishers, which crippled the prospects of some writers.

Cronin: Scottish doctor and novelist, best known for The Citadel (1937), which helped to establish Britain’s National Health Service (and won the American National Book Award). Published several dozen other novels and story collections, including The Green Years, which spent seventeen weeks on the NYT Bestseller List.

A Bell for Adano: Hersey’s third book [preceding the indelible, Hiroshima (1946)]. Awarded the 1945 Pulitzer.

From Wiki:

“ . . . tells the story of an Italian-American officer in Sicily during World War II who wins the respect and admiration of the people of the town of Adano by helping them find a replacement for the town bell that the Fascists had melted down for rifle barrels.”

Strange Fruit: [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lillian_Smith_(author)]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strange_Fruit_(novel)Amber:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forever_Amber_(novel) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathleen_WinsorBasheer (aka Beypore Sulthan): India is one nation but (like many others*) has multiple language streams. Basheer wrote in Malayalam, one of India’s classical languages, spoken in the Southwestern state of Kerala.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balyakalasakhi

*Example, from Spain: Eva Baltasar [Permafrost (2018)] writes in Catalan; Kirmen Uribe [Bilbao–New York–Bilbao (2009)] writes in Basque.

Borges: Astute followers of this Substack will recall that this collection was cited in Birth Year Project 1956, and are perhaps thinking, Hey, what gives—? Wiki explains:

“In 1941, Borges's second collection of fiction, El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan (English: The Garden of Forking Paths) was published. It contained eight stories. In 1944, a new section labeled Artificios ("Artifices"), containing six stories, was added to the eight of The Garden of Forking Paths. These were given the collective title Ficciones. Borges added three more stories to the Artifices section in the 1956 edition.”

Gigi: Here’s the Wiki on the original by Collete:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gigi_(novella)

I haven’t read it, haven’t seen the 1958 film with Leslie Caron, Maurice Chevalier and Louis Jourdan, nor the 1973 Lerner and Lowe Broadway musical, nor its 2015 revival with Vanessa Hudgins. However: do yourself a big favor (if you can access the Times) and read Charles Isherwood’s review from 2015, especially the comments section. A wonderful display of opinion re: political correctness, sanitizing/infantilizing sexual material . . . including a brisk back and forth about whether Maurice Chevalier’s character is or is not a pedophile.

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/09/theater/vanessa-hudgens-in-a-squeaky-clean-gigi-on-broadway.htmlLagerkvist: Milan, the Renaissance, fictionalized Leonardo da Vinci, narrated (via a diary) by a misanthropic assassin. From Wiki:

“. . . a searching, ironic tale about evil, was the first to bring him positive international attention outside of the Nordic countries.”

Most-famous work is probably Barabbas (1950). Lagerkvist was the 1951 Nobel Laureate.

Harvey: Invisible Rabbit? Jimmy Stewart? That one.

[Except the bunny is actually a púca (Irish for spirit/ghost), puca (Old English for goblin) pwca, pooka, phouka, puck . . . from Celtic, English, and Channel Islands folklore.]

https://www.historymatterscelebratingwomensplaysofthepast.org/playwrights/view/Mary-ChaseHartley: From a post @ Goodreads:

Oh, L.P. Hartley, why are you forgotten?

And from another: I haven't come across a depiction of childhood as tender and nuanced as this since, well, David Copperfield or Great Expectations. Hartley does here what Dickens does so well—he captures the voice and perspective of a boy in an adult world.

Hartley’s most widely known novel is The Go-Between (1953)—source of the film of the same name (1971)—Alan Bates, Julie Christie, screenplay by Harold Pinter.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L._P._HartleyLost Weekend:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lost_Weekend_(novel)Anna and the King of Siam: Anna Harriette Leonowens was an Indian-born British writer, teacher, and social activist whose memoir, The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870) Landon fictionalized [she and her husband taught in Thailand (1927-1937)]. The novel was eventually a million seller; the musical rights were sold to Rogers and Hammerstein.

Michaeux: I can’t find out much about this novel, but I’m including it here so you learn about Micheaux. He published seven books, but is known primarily as a pioneer of Black film, producing forty-some “race movies,” as they were called, straddling the silent and talkie eras. Read about his life and work here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_MicheauxCary: Another favorite novel of mine—third of a trilogy [with Herself Surprised (1941) and To Be a Pilgrim (1942)]. Dark humor, the fate of Gulley Jimson, painter with a grandiose vision, scoundrel, chronically underfunded. My introduction to Jimson was via Alec Guinness in the movie of the same name (1958). You haven’t seen it? Really? Do!

But back to the novel: Here’s a taste of Gulley’s voice as narrator:

No one in the bar but Coker. “Is it Willy again?” I asked her. Willy was Coker’s young man. A warehouse clerk shaped like a soda water bottle. Face like a bird. All eyes and beak. Bass in the choir. Glider club. Sporty boy. A sparrowhawk. Terror to the girls. Coker was church, teetotal and no smoke. Willy her only weakness.

Maugham:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Razor%27s_EdgeWalker: Treasured by many Montana writers [along with Black Cherries by Grace Stone Coates (1931)], one of her 13 novels.

Six Degrees of Separation Department: Mildred was married to cardiologist Ferdinand Schemm; their daughter Ripley Schemm became a respected teacher and writer in her own right; in mid-life, Ripley married Northwest poet Richard Hugo; she and Dick were central figures in Missoula’s literary life when I was a stripling [Dick, along with Bill Kittredge, were my principal mentors].

Mildred Walkers Winter Wheat is a treasure. Discovered it in the 90s.

I have read all of Mildred Walker and was fortunate to interview her during the time her books were being reprinted, one after the other, by Univ. of Nebraska Press (Bison Books). I'm pretty sure I haven't ever read Cary's The Horse's Mouth but the short excerpt you gave us made me laugh, and makes me think I need to get hold of a copy. I have read several of the "well-known" books, one of the international titles (Ficciones) and I've seen some version of each of the three plays plus two from the "special mention" list. I guess most of these titles (published almost 80 years ago, now) are no longer showing up on college syllabi but I hope some of them remain familiar titles to those of us who read a lot? It has to be a good sign that my local library has a copy of The Horse's Mouth. Of course who knows? I might be the first person to check it out in 20 years....