Reading Projects [21]: Seeing Triple

The Art of the Trilogy

The world is very much with us these days. Prepping these posts is a labor of love for me (also of brain-cell retention) . . . but even more, now, an oasis from the appalling state of the body politic. As I’ve said before and will keep saying: I promise not to waste your time. Thanks for sticking around. I hope you’ll find new intel about lesser-known books in every post, as well as an encouragement to read off the beaten path.

Special Request: Small-Press Titles

It’s time to update a a post from last year: I asked you to name a few fiction titles from small/indie presses you really liked and think the rest of us should know. We were a smaller number then; the response was thinnish. Our numbers are more robust now and I think we can come up a good new list. Leave a note in the comments, or email me [fallboy52@hotmail.com].

On the Nature of Trilogies

1. Revisiting:

It’s tempting to revisit your characters. They’re yours. Some you love, some you miss, even grieve over. They may be sealed in amber for readers, but they’ve kept living in you. And, on top of all else, returning to them means not having to re-invent the wheel.

But, right away, a conundrum. Whether your novel started with a plot idea (around which, like crystals collecting on a string in sugar water, your “bright, human image” came to be)—or whether the bright, human image was already in you, begging for a drama to act in, the story you wrote, the one already out in the world, depicts the most consequential episode in your character’s life—otherwise why write it?

2. Lesser, Later, Before

If what I just said is true, returning to your character means writing about:

a less-consequential episode . . .

later events in that life . . .

or what led up to the first book—its backstory/pre-story, in detail.

We can ditch lesser right off the bat.

So, later and earlier.

3. The Exemption

Here’s where we get to the main difference between a trilogy and a series.

The writer of a series gives the players a kind of eternal present to occupy. I say “kind of” because in crime or spy novels or the like, the character exists in a zone of time that can expand to hold as many unrelated “cases” or “adventures” or “affairs” as the writer has the will or energy to write.1 Sometimes there’s a passing reference to a past one, and over the arc of many books a character may age, or (less often) suffer some serious change of circumstance. But, essentially, these books = known quantity in new drama. If they catch on with readers they become a brand, a franchise. Writers promise to produce new iterations, readers promise to keep buying them. The contract’s fine print says the character can evolve, but the essential nature of the stories must remain. And so we have Miss Marple, Katniss Everdeen, George Smiley, Philip Marlow, Easy Rawlins, Jack Reacher, Jason Bourne, Nancy Drew, Ethan Hunt, Stephanie Plum, Jack Aubrey, Lisbeth Salander, James Bond, and their multitudinous cohort.

Today’s post isn’t about them.

4. Trilology

We’re looking specifically at trilogies and they do occur in time.

We began with the “you’ve already written the most important thing about someone’s life” problem. What follows, below, is a look at the strategies trilogy writers (trilologists?) have used to circumvent it.

But first, how this dilemma surfaced for me:

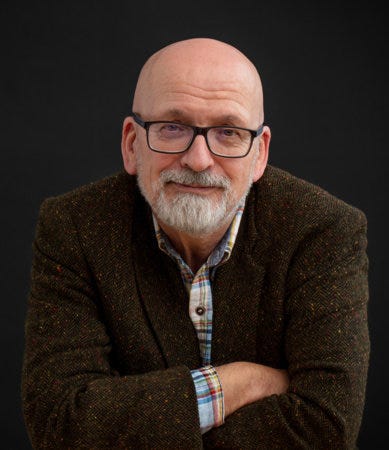

After grad school I converted from poet to fiction writer, planned on sticking with short stories . . . but suddenly had a two-book deal that included a novel—an entirely hypothetical novel I need to point out. Over the next two years, I somehow wrote The Falling Boy2—about the four Stavros sisters and their father Nick who owned the Vagabond Cafe in Sperry, Montana. I considered it a one-off.

I was still (in my mid-forties) trying to figure out who I was as a writer, what I actually believed about this odd calling. I realized that making each project a fresh aesthetic experiment was one of my tenets. So I left the Stavros sisters behind—especially the one I’d fallen in love with, the oldest, Linny—and moved on.

Twenty years went by.

One day, at loose (or wits’) ends, I opened a new file and named it Linny, Later, then tried to see what had befallen my characters. I’d love to report that all went swimming-ly at this reunion. It did not. But that’s a tale for another day.3 I bring it up here just to say a writer’s connection to past work can simmer away, out of sight, and because, while most multi-book projects are designed before the writing begins, some aren’t. Some prior stories wage a stealth campaign for your attention until—years later, maybe—the need to say more about the people in the first book becomes irrepressible.

5. The Fine Print:

Look up “favorite trilogies” and you find: The First Law Trilogy (Joe Abercrombie), The Hunger Games (Suzanne Collins), Fifty Shades of Grey (E. L. James), The Broken Earth Trilogy (N.K. Jemisin), The Poppy War Trilogy (R.F. Kuang), His Dark Materials (Philip Pullman), Divergent (Veronica Roth), The Lord of the Rings (J.R.R. Tolkein). None are in today’s post. Nor the four hundred others Goodreads readers list, by writers whose names ring no bell (for me). This speaks to the gulf between readers of literature and readers of pure genre fiction.

There are writers whose work straddles both camps, of course; loyal followers of this Substack know I have a soft spot for speculative/slipstream/alt-world stuff (a few of these are in today’s post).

THE STRATEGIES

1. It’s all one story:

Some trilogies read like three chunks of one story. All the material might’ve fit in a single volume . . . except:

it would’ve been a doorstop, physically off-putting for publisher and reader—

separate books have room for fine detail, fuller scenes, more players—

you saw that your one big story has a natural three-part structure—

or maybe the later events have yet to play out fully, or your thoughts on what they mean are incomplete/fuzzy; breaking the one big story into separate volumes buys you time, and, if you’re lucky, builds an audience for books two and three.

Sometimes the “one big story” is simply: “What I did in my life”—or, a certain period within it. Example:

THE ROSY CRUCIFIXION, Henry Miller

Sexus (1949)

Plexus (1953)

Nexus (1959)

A garrulous and unfettered first-person account of six years in the life of his alter ego. Today, we’d consider this auto-fiction.

Miller was among the ex-pats in Paris in the 20s, but nearly a generation older than the likes of Hemingway and Fitzgerald. He led a long and storied life.4

Many trilogies enact some version of Miller’s scheme—contiguous segments of a single life.

In other cases, the One Big Story, while still focused on a central figure/figures, is encased in a historical context that needs the space to fully unfold, and a structure that breaks the whole into manageable segments, as in Hilary Mantel’s masterful Wolf Hall Trilogy [aka The Thomas Cromwell Series]:

Wolf Hall (2009)

Bring Up the Bodies (2012)

The Mirror & the Light (2020)

The Trilogy immerses us in an epochal era of British history, the combustion of Henry VIII’s ego and its legacy. Wolf Hall won the 2009 Booker, among other awards. Some historians carped about Mantel’s overly sympathetic depiction of Cromwell,5 but the books were wildly popular. Only recently, I discovered she’d accomplished this massive project while suffering from chronic pain.6

Mantel focused on the royal court, on the makers of history; often writers take the opposite approach, showing us “ordinary people” impacted by the machinations of those in power. In Olivia Manning’s BALKAN TRILOGY, for example, we follow a young English couple, the Pringles, just married and living in Bucharest on the eve of Hitler’s Third Reich. More in the note.7

The Great Fortune (1960)

The Spoilt City (1962)

Friends and Heroes (1965)

2. It’s about a community:

Faulkner wrote what’s known as The Snopes Trilogy:

The Hamlet (1940)

The Town (1957)

The Mansion (1959)

But his lesson for me came from his earlier novels and stories. He wrote about a place, Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi. I never much bothered with how faithful it was to the actual Mississippi. It felt real—saturated with history/character/ incident. From Faulkner I learned to draw a circle around a tract of fictional geography (Sperry County, Montana). Sperry was inspired by the place I lived, but I owned it and could change it at will. Outside that circle, I left things as they were, the names, the facts of history (mostly).

Yoknapatawpha belonged to Faulkner; he populated it, he knew the intersecting back stories of his players—they were, for me, like the denizens of Lake Woebegone; it mattered not whether I could keep them all straight, nor how tightly they resembled real-world Minnesotans. I bought Keillor’s characters for the same reason I’d bought Faulkner’s—because I trusted the source, because the testimony felt intimately known, unimpeachable.

And so another strategy is to write about the inhabitants of a place on Earth, a region, town, valley—or some smaller containing unit, a school or hospital factory . . .8

Elizabeth Strout’s fiction has this in common with Faulkner. She’s published a trilogy of Lucy Barton novels9:

My Name is Lucy Barton (2016)

Anything Is Possible (2017)

Oh William! (2021)

Lucy has since re-appeared in another novel (I’m still calling the first three a trilogy). My bigger point is that trilogies are commonly grounded in geography. Strout’s characters come from (or move to) small-town Maine; some overlap—starring in some novels, taking supporting roles in others. Often these novels have the collective memory of a place to work with—reputation, rumor, differing accounts. Everyone knows everyone else—or so it seems, as in Lake Woebegone. Even when characters don’t overlap, novels in this species of trilogy feel bonded with each other, saturated by the particular localness of the place.

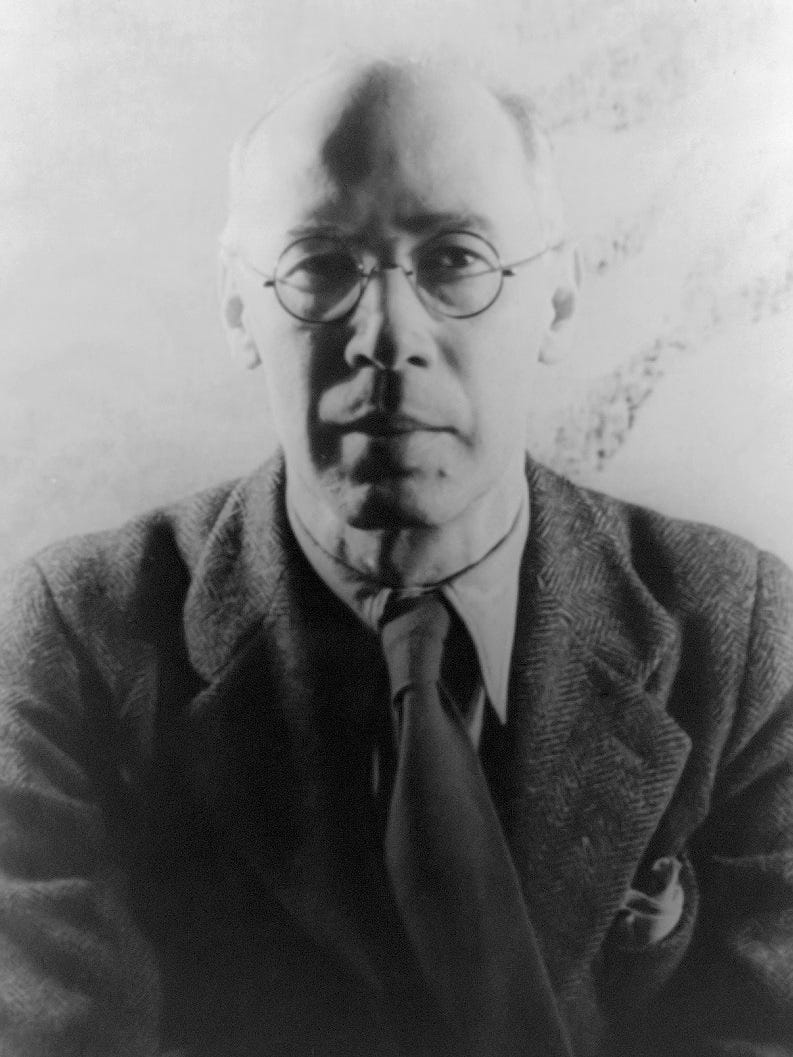

Similarly, Naguib Mahfouz’s, THE CAIRO TRILOGY, is rooted in the Cairo of the past century, but here the story is filtered (as in One Hundred Years of Solitude), through generations of one family.

Wiki’s intro:

The trilogy follows the life of the Cairene patriarch . . . and his family across three generations, from 1919 (the year of Egyptian Revolution against the British colonizers ruling Egypt) to almost the end of the Second World War in 1944. The three novels represent three eras of Cairene socio-political life, a microcosm of early 20th century Egypt, through the life of one well-off Cairo merchant, his children and his grandchildren.

More on Mahfouz.10

THE CAIRO TRILOGY:

Palace Walk (1956)

Palace of Desire, (1957)

Sugar Street (1957)

3. Connected by Status/History/Theme:

There are trilogies with no characters in common, no common neighborhood, no common pursuit/workplace/bailiwick/condition/etc., and yet still form a set within the body of a writer’s work.

A great example is J. G. Farrell’s, THE EMPIRE TRILOGY:

Troubles (1970)

The Siege of Krishnapur (1973)

The Singapore Grip (1978)

A few weeks ago, I finally knocked off the last of these, and was reminded what a fine writer Farrell was . . . and wished he hadn’t died young (at age 44, he left London for County Cork, Ireland, where he fell into the sea while fishing from a rocky outcrop). "There is no question that he would today be one of the really major novelists of the English language,” Salman Rushdie later wrote. “The three novels that he did leave are all in their different way extraordinary."

As the title says, they focus on British Colonies: Troubles (The Irish War of Independence, 1919-1921), The Siege of Krishnapur (India, The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857), The Singapore Grip (the weeks leading to the Japanese capture of the Malay Peninsula in early 1942, as experienced by barons of the rubber export business, their families, assorted military bigwigs, and a miscellany of others.

The novels are often called satire—of the British Empire’s view of their world—but they’re also rich in historical fact and are satisfying reads. Several times in my posts I’ve quoted lines from the Indian book to show how jarringly effective a deadpan delivery can be. The Singapore Grip is rife with them as well.11

8. Not Even Theme

Learned a new term today: poioumenon. Coined by critic, Alastair Fowler, it refers to to metafiction where the story is about creating the story. He applied it to Samuel Beckett’s trilogy:

Molloy (1951)

Malone Dies (1951)

The Unnamable (1953)

Despite being a native English speaker, Beckett switched to French midlife, preferring the clarity and simplicity of French, he said—it let him write "without style.” He (sometimes with a collaborator) later translated the plays and novels into English.

He never called these three a trilogy (he disliked the term for some reason) but they’ve always been seen as linked.12

They’re not an easy read—each a little harder to hang onto than the one before. Gradually, he stripped away the elements of conventional storytelling. By The Unnamable all that’s left is bare consciousness locked in paradox.13

TEN OTHER TRILOGIES

THE OUTLINE TRILOGY, Rachel Cusk14

Outline (2014)

Transit (2016)

Kudos (2018)

THE PASSAGE TRILOGY, Justin Cronin15

The Passage (2010)

The Twelve (2012)

The City of Mirrors (2016)

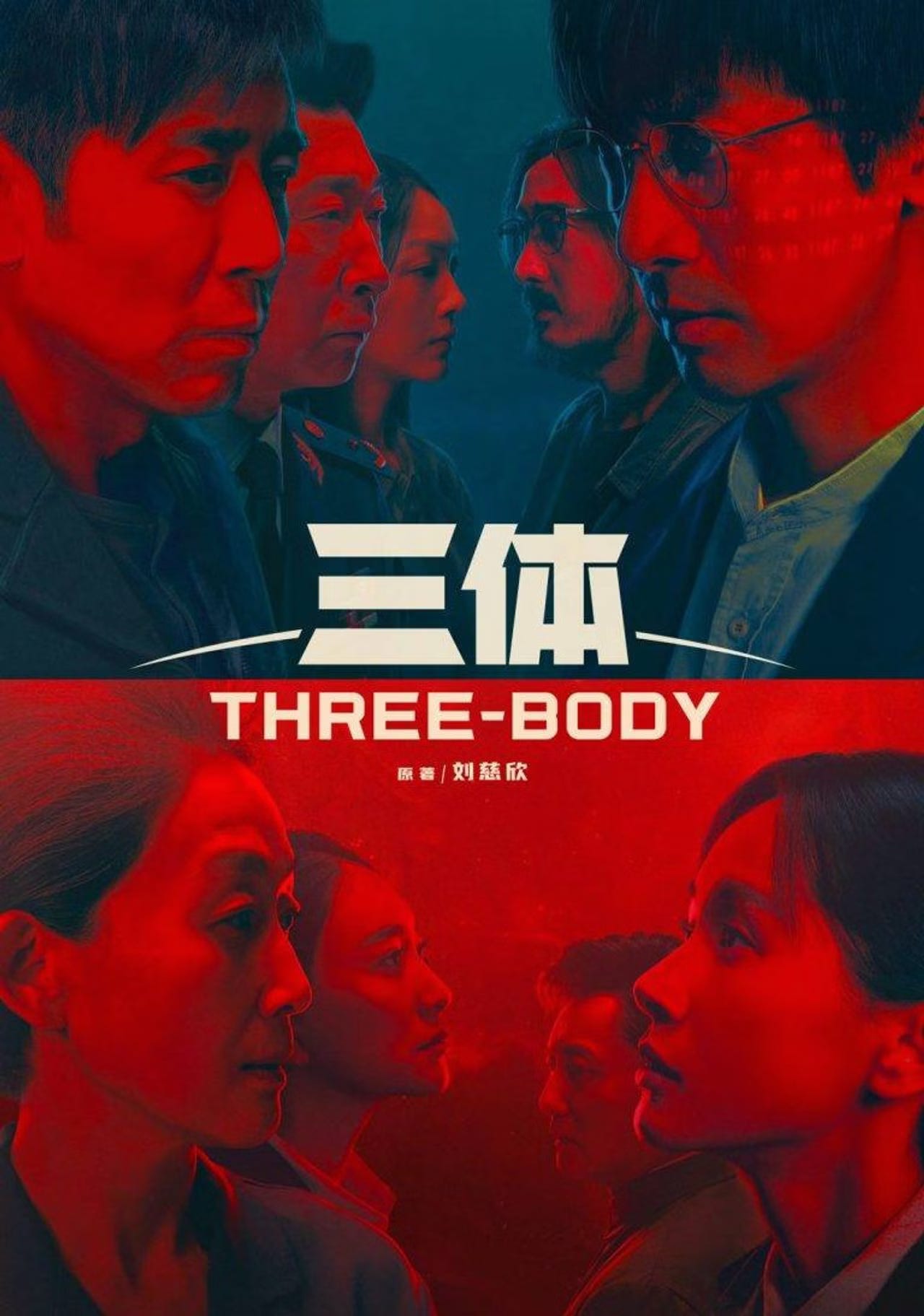

REMEMBRANCE OF EARTH’S PAST TRILOGY, Liu Cixin16

The Three-Body Problem (2006)

The Dark Forest (2008)

Death’s End (2010

THE BORDER TRILOGY, Cormac McCarthy17

All the Pretty Horses (1992)

The Crossing (1994)

The Cities of the Plain (1998)

THE BARRYTOWN TRILOGY, Roddy Doyle18

The Commitments (1987)

The Snapper (1990)

The Van (1991)

THE NEW YORK TRILOGY, Paul Auster19

City of Glass (1985)

Ghosts (1986)

The Locked Room (1986)

THE REGENERATION TRILOGY, Pat Barker20

Regeneration (1991)

The Eye in the Door (1993)

The Ghost Road (1995)

THE COPENHAGEN TRILOGY, Tove Ditlevsen21 (1967-1971)

Childhood

Youth

Dependency

THE AFRICAN TRILOGY, Chinua Achebe22

Things Fall Apart (1958)

No Longer at Ease (1960)

Arrow of God (1964)

THE FIRST TRILOGY, Joyce Cary

Herself Surprised (1941)

To Be a Pilgrim (1942)

The Horse’s Mouth (1944)

THE U.S.A. TRILOGY, John Dos Passos23:

The 42nd Parallel (1930)

Nineteen Nineteen (1932)

The Big Money (1936)

10. The Reading Project:

a) Read the first book of a trilogy—one from today’s post, or from your own sleuthing, preferably one you know little about.

b) Once you’re done, write a paragraph about why the first book makes you want to/want not to read the others. It can also touch on why you favor (or not) trilogies in general, as an art form.

c) Pick a different trilogy and read the books back to back to back, within this calendar year.

Extra credit: If you’re a novelist, explain why you’ve never written a trilogy . . . unless you have, in which case, write about that.

Will or energy: As we know, the hero of the biggest-selling genre novels often survive the passing of their creator—the Millenium Series (aka the Dragon Tattoo/Lisbeth Salander novels) were continued by David Lagerkrantz, then Karin Smirnoff after Stig Larsson’s sudden death in 2004. In other cases, the books are ghostwritten from outlines/ideas from the writer named on the cover (I first learned about this years ago when a friend in Missoula wrote Don Pendleton pulps for a flat fee—inside, on the copyright page, he’d be thanked for his “help” or “contribution”); later I came to see how widespread a practice it is.

[As a kid it had never occurred to me that “Franklin W. Dixon” was actually a cadre of faceless scribes cranking out the Hardy Boys mysteries. Ditto Carolyn Keene/Nancy Drew.]

The Falling Boy: Scribner, 1997.

Linny, Later: Maybe all fiction writers have imaginary books like this one. I’m not sure describing this project’s crash would be all that illuminating—anyway, that’s not why I brought it up.

The Rosy Crucifixion:

Miller had already established his bona fides with The Tropic of Capricorn (1931) and The Tropic of Cancer (1934). These two and the Trilogy were banned for obscenity; his publisher, Grove Press, eventually (1964) succeeded in challenging the laws.

He’s a complex figure—you should get an overview of his life:

And of the Trilogy:

It’s been years since I’ve read him; I have no good sense of how my much-older self would respond. When I was young, I was hot to know all the writers who wrote outside the box, who ignored norms, who feasted on life. With Kerouac, I championed books like Dharma Bums (1958), but he became a sad figure in the end, and some of his writing is barely readable. Miller would fare poorly in the era of #MeToo/cancellation, I think.

I think I said, in an earlier post, that as a young guy I’d loved his memoir, The Colossus of Maroussi, about his move to Greece as WWII approached. In the 90s, I tried rereading it and gave up. Would I feel the same about the Tropic books, the Trilogy? Dunno, maybe. But he’s not a writer who should be forgotten.

Cromwell: Historian Sir Simon Schama wrote that Cromwell “was, in fact, a detestably self-serving, bullying monster who perfected state terror in England, cooked the evidence, and extracted confessions by torture."

Pain:

https://womanmagazine.co.nz/author-hilary-mantel-on-losing-her-religion-living-with-chronic-pain-and-the-monarchy/

Manning: I’d heard the name, that’s about it. Turns out she’s one of a cadre of early to mid-20th C. women writers whose fiction has—despite its indisputable worth—dropped from sight. We still read Marguerite Duras, Patricia Highsmith, Shirley Jackson, Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, Muriel Spark; a few others have been rediscovered—Zora Neale Hurston (Their Eyes Were Watching God, 1937), and Dawn Powell—The Library of America has issued nine of her novels in two volumes, including my favorites, The Locusts Have No King (1948) and The Wicked Pavilion (1954).

But this leaves a slew of estimable women novelists we don’t read. Some I’ve worked into earlier posts: Harriet Arnow, Barbara Comyns, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Jetta Carlson, Ellen Glasgow, Theodora Keogh, Jean Stafford, Grace Stratton-Porter, Rosemary Tonks . . .

Anyway, working on this post, I discovered The Balkan Trilogy, and have been sucked into the first volume’s world this week—had one of those, Oh, she can really write moments.

Manning followed this triplet with a second one, The Levant Trilogy: The Danger Tree (1977), The Battle Lost and Won (1978), and The Sum of Things (1980). The two trilogies have since been published together under the title Fortunes of War.

Community: A post from a year ago: Ship of Fools: Novels About Communities.

Elizabeth Strout: Her novel third novel, Olive Kittredge, won the 2009 Pulitzer; others have been long- and short-listed for the Booker. She also has a law degree.

Mahfouz: Americans don’t read much writing translated from Arabic, thus, despite being a Nobel Laureate (1988), Mahfouz is under-read in English. Check out the Cairo Trilogy here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cairo_Trilogy

The English translations appeared as follows:

Palace Walk [trans. by William M. Hutchins and Olive Kenny (1990)]

Palace of Desire [trans. by William Hutchins, Olive Kenny, and Lorne Kenny (1991)]

Sugar Street [trans. by William Hutchins, Olive Kenny, and Angele Botros Samaan (1992)

In 2016, Everyman’s Library published the trilogy in one volume.

Singapore Grip: The black humor continues throughout, but the way the reality of the invasion finally becomes real for everyone is quite effective—dramatic, full of human insight and insider detail. And: one of the young men, new to town, keeps trying to learn what “The Singapore Grip” actually is—Farrell makes him (and us) wait until p. 498.

Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable: Beckett has been studied, written/argued about extensively. He had a remarkable life, really—besides his writing/theatre life, he met James Joyce in Paris in the 1920s, was mentored by him and was, for a time, his secretary/researcher. When France fell to the Nazis, he was active in the French underground. He lived until 1989. The Net is rife with links to Beckett stuff—start here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Beckett

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Molloy_(novel)

https://www.ulysseswhiskey.com/post/the-profound-and-complex-relationship-between-samuel-beckett-and-james-joyce

More Beckett: Wanted you to see a snippet of an essay I did that touches on Molloy:

Before launching myself into Beckett’s three linked novels . . . I had the idea, based on photographs of his hawkish face, some very dated memories of Endgame and Krapp’s Last Tape, and the fact he’d abandoned English for French, that he’d maybe read like Sartre—that is, having the peculiar pallor of 40s and 50s Existentialism. I began Molloy with my guard up.

We find the narrator at his mother’s, in a state of confusion. How did he get here? He’s not sure. Then there’s this (we’re still on the first page):

The truth is I don’t know much. For example, my mother’s death. Was she already dead when I came? Or did she die later? I mean enough to bury.

Enough to bury? I’m sorry, this put me in hysterics. I had him all wrong. Forget French. This was the black, self-lacerating humor of Irish pub stories, of wakes. If you don’t hear the undercurrent of fierce comedy in Beckett, he makes no sense at all.

Cusk:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outline_(novel)

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-new-yorker-interview/i-dont-think-character-exists-any

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/apr/30/kudos-rachel-cusk-review-final-part-trilogy

Cronin:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Passage_(novel_series)

Three-Body: About the English translations:

The Three-Body Problem [trans. from Mandarin Chinese by Ken Liu, 2014]

The Dark Forest ([trans. from Mandarin Chinese Joel Martinsen, 2015]

Death’s End [trans. from Mandarin Chinese by Ken Liu, 2016]

This is a monumental body of hard science-fiction (that’s a genre, BTW, not a comment on its ease of reading). There are two TV versions, one American (set in China and England), one Chinese. The American production, The Three-Body Problem, ran in 2024 (8 episodes/Netflix); it will continue in 2026. The Chinese production, Three-Body, has 30 episodes. Both shows reconfigure the original, but both are gripping. Both are high-budget feasts for eye and mind. I won’t say more here—too complex a storyline.

Read about the novels, watch both shows.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remembrance_of_Earth%27s_Past

The Border Trilogy: Here’s AI’s nutshell:

All the Pretty Horses: Focuses on John Grady Cole's journey across the border.

The Crossing: Centers on the adventures of Billy and Boyd Parham.

Cities of the Plain: Unites John Grady and Billy, allowing the reader to see how their stories connect and influence each other.

Doyle:

Many of us first heard of Doyle via the film version of The Commitments. Dublin, local blokes and blokettes cobble together an R & B band. I wish I could see it again for the first time. Barrytown is Doyle’s fictive slice of Dublin. His novel, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha won the Booker Prize in1993. Technically, since he’s added a couple more Barrytown novels, this would count as a series, but the first three have been printed as trilogy and I’ll stick with that.

Auster:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_York_Trilogy

From a blurb: The Trilogy is a postmodern interpretation of detective and mystery fiction, exploring various philosophical themes.

I came to Auster late and haven’t read the trilogy yet, but I can vouch for Man in the Dark (2008) and In the Country of Last Things (1987).

Pat Barker: Set at the end of WWI, blending real people and fictional characters.

Part of Wiki’s overview::

The broad themes outlined across the three books are the modernisation of medicine in the treatment of trauma and mental illness with its differing application in relation to social class — the progressive and considerate cutting-edge Freudian treatment for officers versus the regressive, aggressive, and brutal aversion therapy for the lower ranks. Also, the theme of sexuality — hetero-, bi-, and homo-sexuality — is prevalent throughout and its interplay again across the social classes.

Copenhagen: Another writer new to me. From a blurb:

. . . one of the most important and unique voices in twentieth-century Danish literature, and The Copenhagen Trilogy (1969–71) is her acknowledged masterpiece. Childhood tells the story of a misfit child’s single-minded determination to become a poet; Youth describes her early experiences of sex, work, and independence. Dependency picks up the story as the narrator embarks on the first of her four marriages and goes on to describe her horrible descent into drug addiction, enabled by her sinister, gaslighting doctor-husband.

LitHub has a double handful of pieces on her, including:

https://lithub.com/the-copenhagen-trilogy/

http://bookmarks.reviews/reviews/the-copenhagen-trilogy-childhood-youth-dependency/

And from The Guardian:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/16/the-copenhagen-tirlogy-by-tove-ditlevsen-review

Achebe: Nigerian, considered the father of modern African writing. The first novel in this set has been on my TBR list for ages—maybe this is the year? In any case, he’s an important figure in African letters—much too much to say about him here. The Wiki is a good place to start:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinua_Achebe

https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/authors/chinua-achebe

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/mar/22/chinua-achebe

Dos Passos: Years ago I stumbled upon his earlier novel, Manhattan Transfer (1925) and was blown away by the writing—I’ve quoted lines from it earlier posts. Oh hell, here’s a couple, again:

She stood in the middle of the street waiting for the uptown car. An occasional taxi whizzed by her. From the river on the warm wind came the long moan of a steamboat whistle. In the pit inside her thousands of gnomes where building tall brittle glittering towers.

“Say Anna,” says a broadhipped blond girl . . . “did ye see that sap was dancin wid me? . . . He says to me the sap he says See you later an I says to him the sap I says see yez in hell foist . . . an then he says, Goily he says . . .”

So why have I never read The U.S.A. Trilogy? Beats me.

Read about that project here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S.A._(trilogy)

I loved Wolf Hall, but couldn’t get into Bring Up the Bodies. Maybe i’ll try again, but I feel like I’d have to re-read Wolf Hall. I thought The Passage, which I read years ago, was just okay. At the time it seemed to me like an idea for a reality show.

Mistake -- go for the tetralogy.