1.

Isolate a group of people then watch what happens. A time-honored dramatic device that span genres—from thrillers and mysteries to literary novels, all sorts of speculative/dystopian/post-apocalyptic and/or horror novels, novels of social commentary—comic, tragic, novels of high purpose and low.

Why? It focuses our attention, it eliminates off-stage possibilities, it puts characters under pressure where, like chemical elements, they behave either differently or even more like themselves, and (thinking specifically of “locked-room mysteries”) it amps up the reader’s fascination as the list of explanations grows smaller and smaller—we’re pumped up not just by what’s going on in the story, but also by wondering how the writer’s going to pull it off.1

Now I planned on giving you a short list of works that use this model, then scooting on to today’s actual subject, except, ahem, that part got just a tad out of hand. Therefore, find it at the end.

2.

Writing about community:

Almost all novels have what, back in schoolhood, we called the protagonist, or the main character—i.e., the center of our attention. Sometimes there’s an antagonist or villain, though this role is commonly farmed out to a situation (disease/addiction, depletion of resources, false accusation, faceless corporation, weather, time, rotten luck,2 etc.), usually within a tight time frame. This set-up has endless permutations.

Our central figure is typically surrounded by a supporting cast—family, co-workers, posse members, teammates, fellow-soldiers/-passengers/-prisoners/-survivors/-escapees, etc. Or maybe there’s only a sidekick, wingman/wingwoman—Sancho Panza, Sundance Kid, Thelma, Dr. Watson, Stan Laurel, Bullwinkle Moose.

But once in a while, we find a work that’s primarily about the group, that treats the band of characters as a community or ensemble, sharing the POV among the players (as in As I Lay Dying, The Canterbury Tales, or A Gathering of Old Men3), depicting the group as a group, as one entity, or passing the focus more or less equally among the group’s members.

And some of these works (often below the surface) want us to consider why there’s no central figure. They want us to watch the group dynamics (or, to say it elsewise: group dynamics may be their subject, the way it is in a film like Twelve Angry Men). Or they want us to see why groups either do or do not need a leader, or want us to watch what happens when one group has less power than another group (as in This Other Eden), and so on.

Ten novels about groups:

This Other Eden, Paul Harding (2023).4 A mixed-race island community off the coast of Maine has lived in harmonious isolation since the 1790s—until confronted by The Powers That Be in 1912. Another lean-but-rich novel from this writer—accrued boatloads of accolades including “Barack Obama’s 15 Favorite Books of 2023.”

Daisy Jones & The Six, Taylor Jenkins Reid (2019).5 The rise and crash of a band (loosely reminiscent of Fleetwood Mac), told via interviews years after the breakup.

Women Talking, Miriam Toews (2018).6 Good novel (source of a good film by Canadian director, Sarah Polley). Women and children in an isolated religious community examining their beliefs, their drugged rape by the colony’s men, their weighing of the prospects of taking action.

The Wives of Los Alamos, TaraShea Nesbit (2014).7 The title says it all. A great example of the first-person plural POV. All the more pertinent considering the film Oppenheimer.

Building Stories (graphic novel), Chris Ware (2012).8 Just like it sounds—the residents of a Chicago brownstone and their stories.

The Night Watch, Sarah Waters (2006).9 During and after the London Blitz, follows a cast of interconnected women (mostly) who collect the dead and maimed. Emotionally complex and written with Waters’ characteristic grace, toughness, and empathy.

The Virgin Suicides, Jeffrey Eugenides (1993). [See Nesbit, above.]

South Riding, Winifred Holtby (1936).10 Citizens of a Yorkshire town between the two world wars—politics, social change, class structure, the role of women, the power of education.

As I Lay Dying, William Faulkner (1930).11 The story of Anse Bundren, world-class cheapskate, and his children trying to honor their deceased wife’s/mother’s one wish: to be buried with her people. As luck would have it, her people are on the far side of a flood-swollen river. A tale of epic ineptitude. Famous for a cast of rotating first-person narrators.

Can You Forgive Her? Anthony Trollope (1865).12 This is the first of the six Palliser Novels [also called the Parliamentary Novels]. It has three parallel love stories, set against the politics of the late 1850s. Trollope’s novels tend to have ensemble casts, but in this one, especially (as in South Riding), the plotlines have comparable weights—despite introducing Plantagenet Palliser, whose career is the subject of the series, the novel feels like a group portrait.

3.

Isolating a Group: Variations on a Structure

THREE CLASSICS:

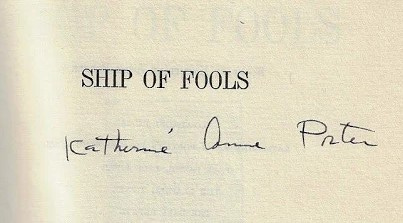

Ship of Fools, Katherine Ann Porter (1962)13

Lord of the Flies, William Golding (1954)14

The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Thornton Wilder (1927)15

SEVEN “PILGRIMS ON THE ROAD” BOOKS:

Fourteen Days: A Collaborative Novel, Margaret Atwood and Douglas Preston, eds. (2024)16

Refugee Tales, David Herd and Anna Pincus, eds. (2016)

Tokyo Cancelled, Rana Dasgupta (2005)

Hyperion (1989) and The Fall of Hyperion (1990), Dan Simmons17

The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer (written c. 1387-1400)

The Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio (written c. 1349-1353)

THREE “LOCKED ROOM” NOVELS BY DAME AGATHA CHRISTIE:

And Then There Were None, (1939)

Death on the Nile (1937)

Murder on the Orient Express (1934)

THREE NOT BY DAME AGATHA CHRISTIE18:

Daisy Darker, Alice Feeney (2022)

Nine Perfect Strangers, Liane Moriarty (2018)

The Hollow Man, John Dickson Carr (1934)

THREE TB SANITARIUMS:

The Rack, A. E. Ellis (1958)19

Pale Horse, Pale Rider, Katherine Anne Porter (1939)

The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann (1924)

THREE MENTAL HOSPITALS:

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey (1962)

The Snake Pit, Mary Jane Ward (1946)

The Outward Room, Millen Brand (1937)

FOUR PRISONS:

Kiss of the Spider Woman, Manuel Puig (1976)

Cool Hand Luke, Donn Pearce (1965)

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1962)

The House of the Dead, Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1862)

FOUR “MIGHT AS WELL BE PRISON” NOVELS:

The Natural Way of Things, Charlotte Wood (2016)

Room, Emma Donoghue (2010)

The Unit, Ninni Holmqvist (2006)

Blindness, José Saramago (1995)20

ONE 12TH CENTURY NUNNERY:

Matrix, Lauren Groff (2021)

FOUR “WORKPLACE ENDING” NOVELS:

Severance, Ling Ma (2018)21

Then We Came to the End, Joshua Ferris (2007)

Last Night at the Lobster, Stewart O’Nan (2007)22

The Waitress Was New, Dominique Fabre (2005)23

THREE COMMUNES:

Arcadia, Lauren Groff (2012)

Drop City, T.C. Boyle (2003)

The Blithedale Romance, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1852)

TWO PRE-APOCALYPSE NOVELS:

On the Beach, Nevil Shute (1957)

The Hopkins Manuscript, R. C. Sherriff (1939)24

SIX SOCIETAL COLLAPSE/APOCALYPSE/POST-APOCALYPSE NOVELS25:

How High We Go in the Dark, Sequoia Nagamatsu (2022)

Station Eleven, Emily St. John Mandel (2014)26

The Road, Cormac McCarthy (2006)

Parable of the Sower, Octavia E. Butler (1993)

The Death of Grass, [U.S. title, No Blade of Grass], John Christoper [pen name of Sam Youd] (1956)

Earth Abides, George R. Stewart (1949)

And you can’t cheat. In the pantheon of writerly sins (up there with boring the reader), is having it turn out that the door wasn’t locked after all.

Luck: My hesitance to add luck to this list goes back to a conversation I had with one of my principle mentors, Bill Kittredge. We were at Bill’s other office (aka The East Gate Lounge in Missoula, Montana—this would’ve been in the mid-1970s). Bill was explaining why you can’t end a story with an accident: it’s cheating, it’s deus ex machina (we’re talking about traditional realism here). Outcomes in fiction should come from a character’s decisions/actions, and those come from who the character is [Basic concept: action reveals character]. Sometimes, in a story, an accident is only superficially accidental—often it’s traceable to an earlier decision or failure to decide. In our world, though, the cosmos does dole out bad luck; it’s a fact of nature and as such has to be included in our stories. But here’s the point: Luck (good or bad) shouldn’t be used to save writers asses when painted into corners. If luck’s involved, it’s what comes after it that counts, what you do because of it. Which is why you can start a story with an accident, but not end on one.

Harding: His slender, exquisite first novel, Tinkers (2009), was the surprise winner of the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Should not be missed. Ditto This Other Eden.

Some years back, I tried to read the passage below to my wife, and we got into one of those insane laughing jags where you can’t catch your breath or look at the other person:

Howard could not imagine this old husk of a man . . . had a tooth left in his head to ache. Nevertheless, it was true. Stepping closer, Gilbert opened his mouth and Howard, squinting to get a good look, saw in that dank, ruined purple cavern, stuck in the back of an otherwise-empty levee of gums, a single black tooth planted in a swollen and bright red throne of flesh. A breeze caught the hermit’s breath and Howard gasped and saw visions of slaughterhouses and dead pets under porches.

Daisy Jones: Riley Keough (granddaughter of Elvis) played Daisy in the 2023 mini-series. She has a wonderful loose-cannon quality—you can’t take your eyes off her (or I couldn’t). The actors actually went to band camp, became a band and performed live. I ate it up. You could argue that the novel is really about Daisy and Billy, but I see it as a group portrait.

Women Talking: Polley is a gifted Canadian filmmaker, social activist, former actor. Read about her here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Polley

Miriam Toews [Tay-vz] has written several times about Mennonite communities. This one has feminist gravitas/liberation at its core; many consider it her best work. I still like All My Puny Sorrows (2014)—two sisters, one with a hunger for suicide (reminiscent of Amy Bloom’s short story, “Silver Water”).

Nesbit: Here’s the note on Nesbit from Voice [2]:

Remarkably effective group portrait. She uses this POV in a way I’ve not seen before. In Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel, The Virgin Suicides, the first-person plural POV represents the collective voice of the neighborhood boys who revered, then mourned, the Lisbon sisters. In The Wives of Los Alamos, this voice expresses the diversity among the cohort of wives—the women behind the men who made the bomb.

Building Stories: I’m no expert on graphic novels, but a couple of earlier ones helped anchor this genre in the world of serious lit: Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale series (1986-1991)—his aging father’s memory of the Holocaust (“The first masterpiece in comic book history”—The New Yorker). And Marjane Satrapi’s, Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood (2003)—coming of age in Tehran.

Building Stories was first serialized in The New York Times Magazine (2005-2006). See also Ware’s earlier work, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (2000).

Another I admire: Here, Richard McGuire (2014)—a house and its occupants through time.

Night Watch: Starting with Tipping the Velvet (1999), she has produced a string of prize-winning, mostly lesbian-themed novels—several set in the past [like Tipping the Velvet, Fingersmith (2002) is set in Victorian Britain]. She’s a dependable writer, the way Anne Tyler or Toni Morrison or Hilary Mantel is—that is, whatever you pick up it will be intelligent and engaging.

South Riding: Semi-autobiographical, published posthumously—Holtby died of kidney disease at age 37. Arguably, Sarah Burton, the school’s new independent-minded headmistress, is the center pole of the story, yet overall it seems a portrait of a place and time (based on East Riding, Yorkshire, on the northeastern coast of England where Holtby was raised). Her other major novel is The Crowded Street (1924).

Faulkner: My favorite Faulkner—a must-read (but you already knew that). There were others who shook up the formal structures of the novel in Faulkner’s era, many influenced by wholesale upheavals in music and painting—Joyce, Gertrude Stein, John Dos Passos, Virginia Woolf, and others, also a slew of poets—but this work, along with The Sound and the Fury (1929), showed that such invention could be used on deeply American material, in this case Southern, steeped in past, as non-urban/non-up-to-date as you could imagine.

Trollope: Trollope published forty-seven novels. Every day before trotting off to his job at the post office, he knocked out 3000 words—at a rate of 250 every fifteen minutes, timed by his watch. And these weren’t slender little books—this Victober I read three, including Can You Forgive Her?, amounting to two thousand-plus pages altogether. Despite the length, they’re quite reader-friendly—not nearly as sentimental as Dickens or as grammatically/syntactically challenging as many mid-Victorians (say George Eliot). I’ll have more on Trollope in a future post.

Ship of Fools:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ship_of_Fools_(Porter_novel)

Golding: A Nobel Laureate. Read about the book/film(s) here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_of_the_Flies

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_of_the_Flies_(1963_film)

Pretty sure I covered this in an earlier post (that I can’t seem to locate); here it is again:

I went to a boy’s boarding school in CT, starting sophomore year. That fall, we all gathered in the auditorium to watch the 1963 film of Lord of the Flies because it starred a member of our class, Tom Chapin. He’d done no acting (they wanted untrained kids), but his father was an artist, and somehow Tom crossed paths with the filmmakers. For the record, Tom went on to became a geologist.

[Sometime, I’ll tell about my own thrilling career in the movies (rifle-toting extra in Michael Cimino’s epic, Heaven’s Gate).]

San Luis Rey: . . . was still widely read when I was a kid. It won the 1928 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. From Wiki:

The Bridge of San Luis Rey tells the story of several interrelated people who die in the collapse of an Inca rope bridge in Peru, and the events that lead up to their being on the bridge. A friar who witnesses the accident then goes about inquiring into the lives of the victims, seeking some sort of cosmic answer to the question of why each had to die.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bridge_of_San_Luis_Rey

[It wouldn’t be a stretch to see Wilder’s most famous work, the play, Our Town (1938), as a group portrait, as well.]

Fourteen Days: Here’s the blurb:

Set in a Lower East Side tenement in the early days of the COVID-19 lockdowns, Fourteen Days is an irresistibly propulsive collaborative novel from the Authors Guild, with an unusual twist: each character in this diverse, eccentric cast of New York neighbors has been secretly written by a different, major literary voice—from Margaret Atwood and John Grisham to Tommy Orange and Celeste Ng.

A dazzling, heartwarming, and ultimately surprising narrative, Fourteen Days reveals how beneath the horrible loss and suffering, some communities managed to become stronger.

Dan Simmons: A prolific writer of sci-fi and other sorts of speculative lit, including The Terror (2007). These two are clearly indebted to The Canterbury Tales; I found them deeply compelling.

Locked-Door novels:

https://www.bookbub.com/blog/locked-room-mysteries

Rack: Can’t remember how I stumbled onto this one—it shares the man-in-a-TB-hospital plot with Mann’s novel, but ends up being, in a way, a love story with great poignancy. It’s a prime example of a novel too good to be forgotten.

Blindness: . . . is a brilliant novel. All over the city, one by one, people go white blind; they’re rounded up and locked away together. The Doctor’s Wife is a great character. Saramago is recognized as a major world writer, but his later novels pale compared to this one—the strangeness of plot he imposes on his characters is harder to buy into . . . But you must read Blindness.

Ma: This could be counted as an “end of the world” novel, but what concerns us today is stories about groups—in this case a community of people who share an apocalypse (as in The Hopkins Manuscript and On the Beach) or become a community during or after a cataclysm, (as in Station Eleven or Earth Abides).

O’Nan: A dependable source of slender well-written novels. With snow falling outside, the employees and a handful of customers share the final night of a chain eatery. A modest, yet moving story. I used to use one of its sentences as an example of how naming names can spike a writer’s credibility/authority—a homely yet perfect sentence:

With oven mitts he delivers the pots to Leron, who dumps them steaming into the gurgling InSinkErator.

The Waitress Was New. This is an Archipelago Books title [as with Persephone, below, I’ll be devoting a post to them soon; I’ve included various books of theirs in earlier posts— “slender novels” and “literature in translation”]. A great example of a small book, a little over a hundred pages, modest in scope but absorbing—like the people in Stewart O’Nan’s story, here a veteran waiter is confronted by the closing of his café.

Sherriff: This is a Persephone Books reprint. I’ll talk more about it in an upcoming post on Persephone. I was much more taken by it than I’d expected. What it shares with Shute’s classic, On the Beach: The characters know when Armageddon will come (only months in the future) and why. Shute takes us up to its brink, focusing on how his cast of ordinary citizens cope with their fate; Sherriff takes us through the event into the changed world it creates. It’s good to remember that it was written when England was prepping for inevitable war with Germany.

Apocalypse novels: These have become ubiquitous—way more than any one human could read in a lifetime. Except for Nagamatsu’s, the titles in this subset are all well-known. The theme has attracted writers from across the spectrum of fiction—from serious literary novels, to horror, action-heavy thrillers, straight sci-fi, political/philosophical/social what-ifs, satires, and wildly speculative category-of-one work.

Mandel: Her work took a big leap forward with this novel. This has a credible scenario, a fascinatingly interwoven cast—though we’ve seen similar plotlines [The Andromeda Strain (1969), The Stand (1978), the film Contagion (2011)], this one somehow makes it new. The mini-series (2021), was a relatively faithful adaptation, featuring Mackenzie Davis from Halt and Catch Fire. Well worth a watch.

Ooooh, I get it....I just took a closer look at the woodcut illustration at the head of this substance. "Ship of Fools" indeed!

I appreciate your consideration of luck.