Reading Projects [16]: Archipelago Books

The world's books in translation

Note:

I wrote this post last year, but never put it up. Archipelago has been busy in the intervening months, so I’ve updated, changed the focus a bit. Think of it as a companion to Reading Projects [10]: Persephone Books:

https://longd.substack.com/p/reading-projects-10-persephone-books

Because Archipelago is heavily invested in works from the non-English-speaking world, I’m also linking today’s post to a three-parter on works in translation I published in the early days of this Substack. Links here:1

If you’re long-time reader of this enterprise, you’ll recognize some of these titles (I keep talking about books I really like).

Reasons to champion Archipelago :

They’re a classy outfit.

They publish books in translation you’d never otherwise know/have access to. They’re the equivalent of an indie station that plays deep cuts.

Reading their books (and those from the other presses cited in the linked translation posts) gives you a more-informed sense of what fiction can accomplish, helps you appreciate the limitations of modern American publishing, and choice of subject.

Like Persephone, they have a great catalog.

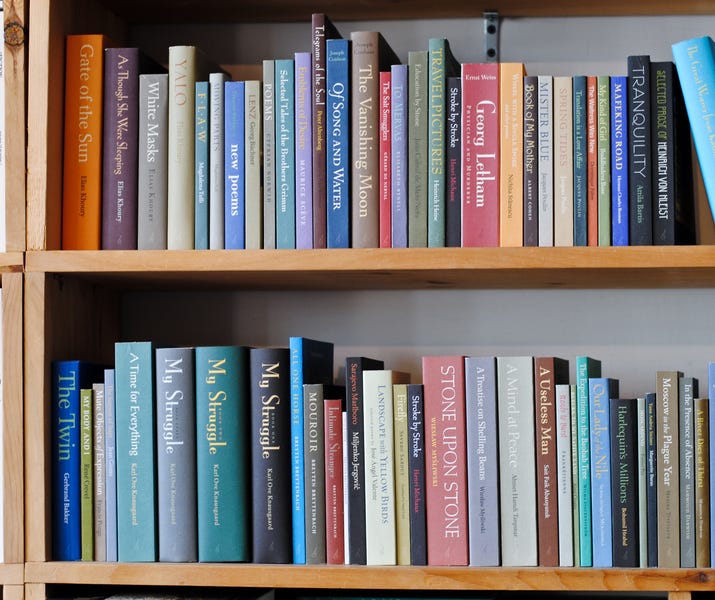

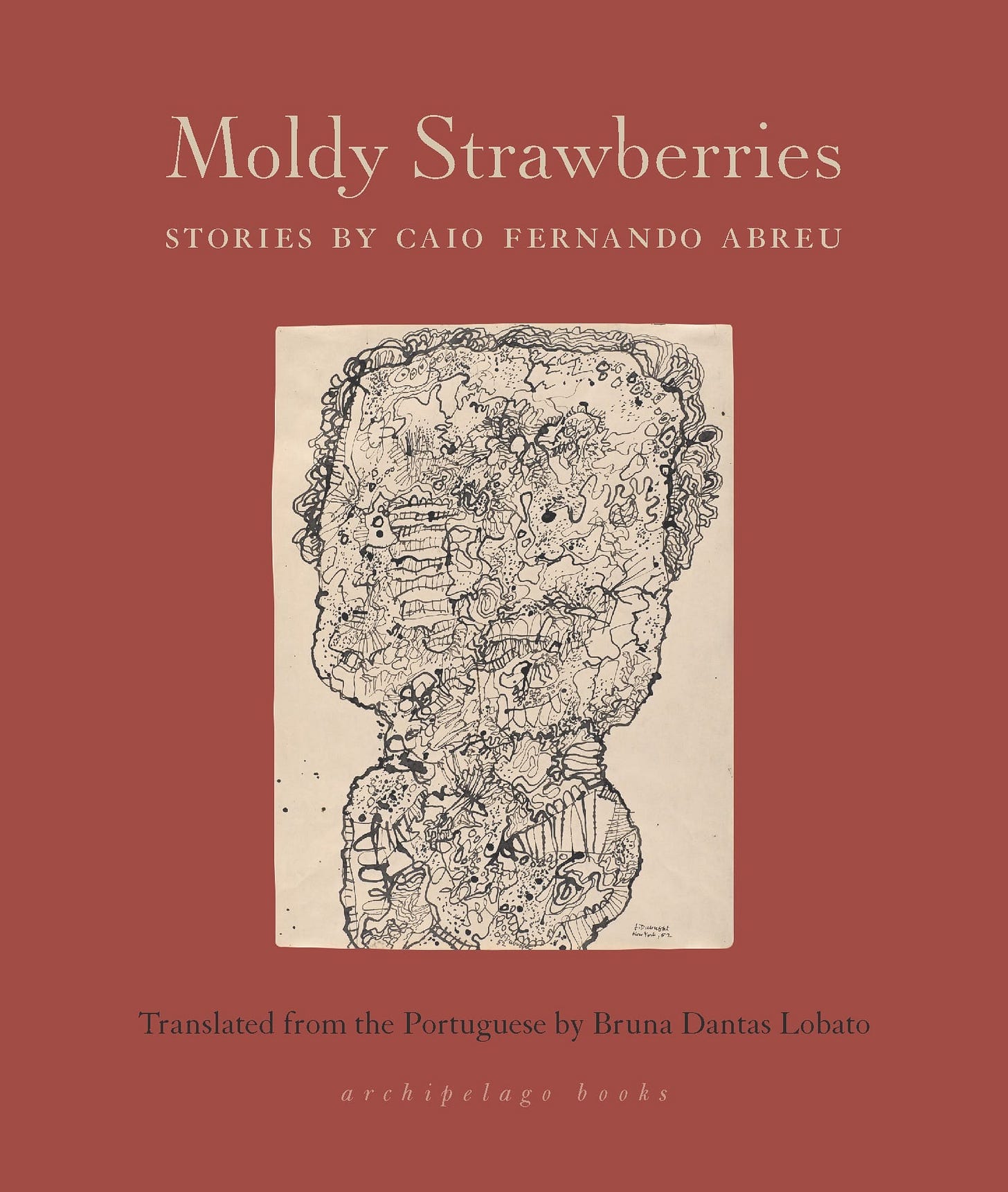

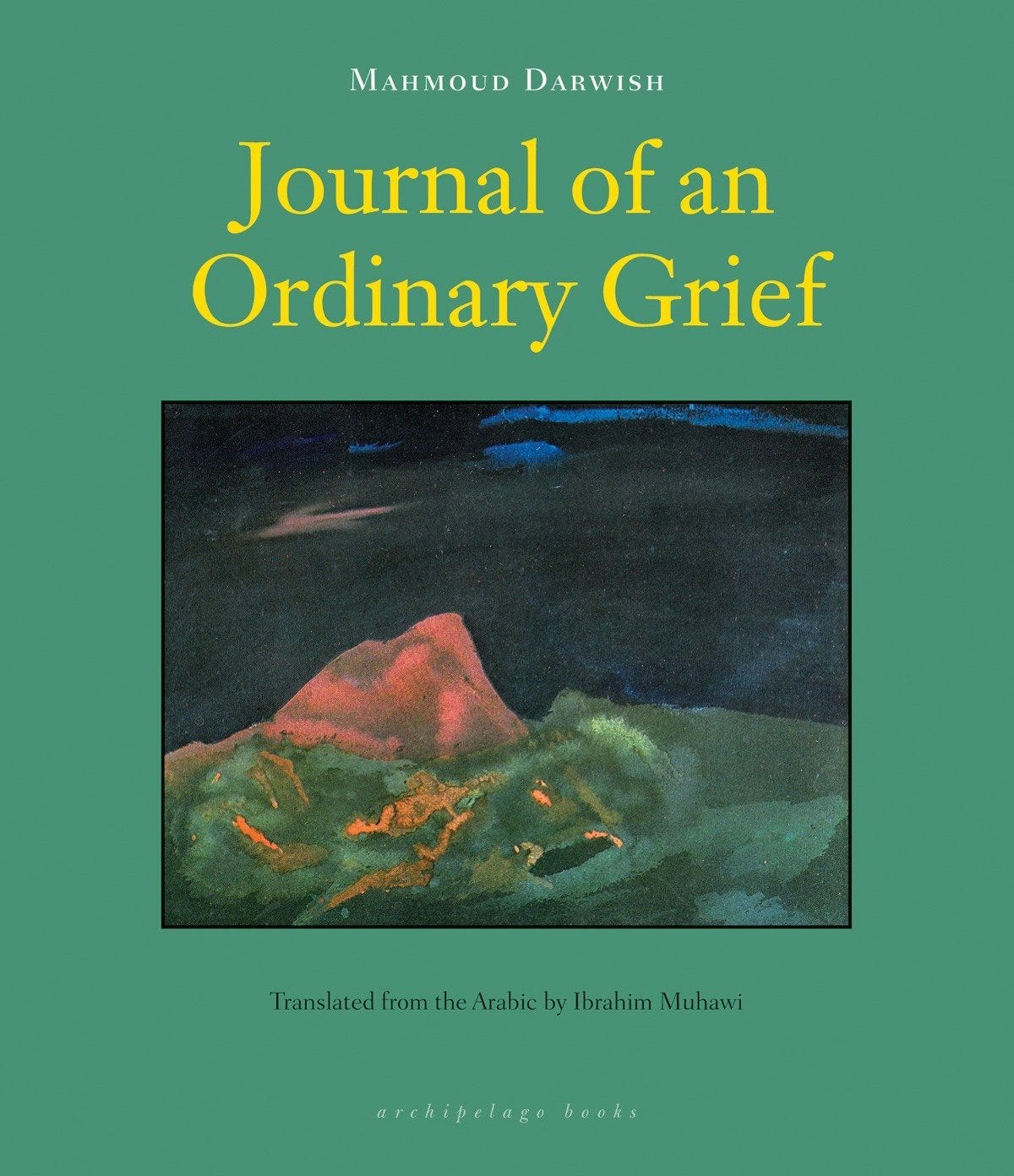

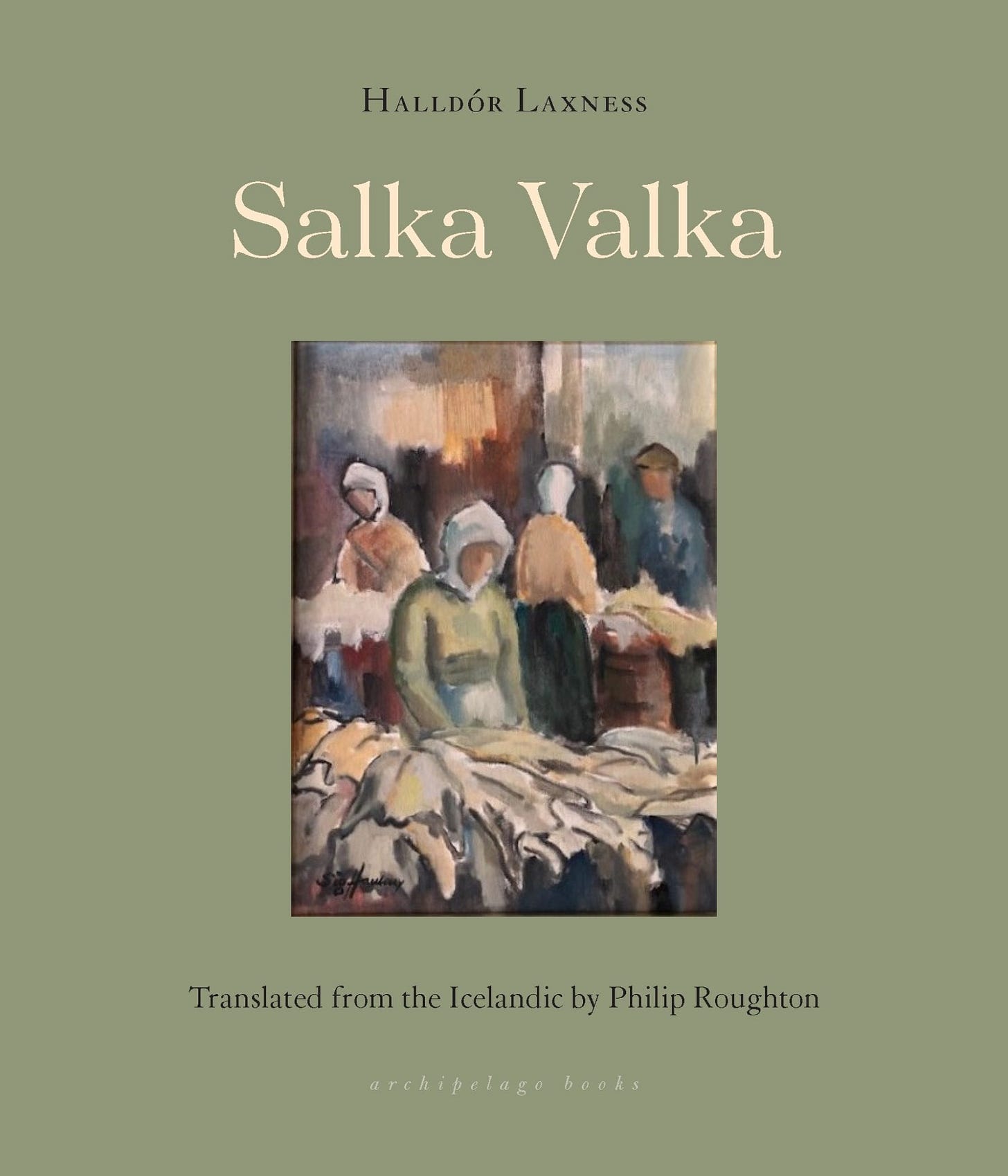

The books are a pleasure to hold in your hand. They’re square, have muted-palette/matte-finish paper covers (with flaps) with an arresting drawing/painting/art-print in the center. This uniform design lets you pick them out easily on library or bookstore shelf (even when only the spine shows), a strategy used by several other presses I’d admire: Europa Editions, New York Review of Books Press, Charco Books, to name a few. This format also (IMHO) tells you someone’s at the helm at Archipelago, that the books aren’t being manufactured by a glitzy marketing machine. In short, I like/trust them before I’ve even looked inside.

If you choose, you can subscribe to the press, then you get surprises in your mailbox every so often.

https://archipelagobooks.org/

Twenty-four Archipelago Titles:

I’ve read about a third of these, a bunch more are stacked by my chair, the rest have had their praises sung by other readers/reviewers/prize-givers. The ones I can vouch for myself are asterisked [*].

Sister Deborah, Scholastique Mukasonga [trans. from French by Mark Polizzotti] (2024)]. Original publication 2022. France/Rwanda.

Kibogo, Scholastique Mukasonga [trans. from French by Mark Polizzotti] (2022)]. Original publication 2020. France/Rwanda. Finalist for 2022 National Book Award.2

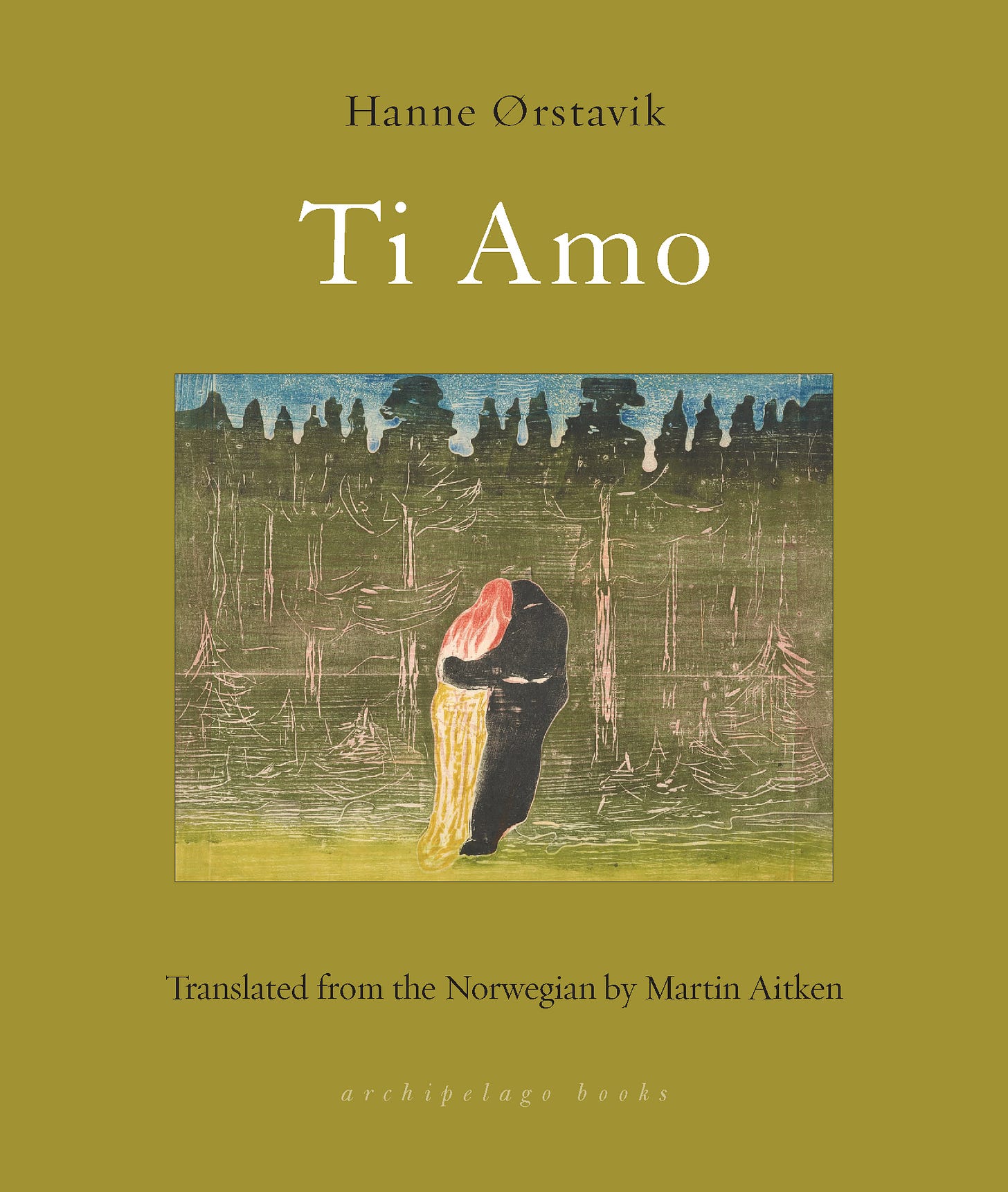

*Ti Amo, Hanne Ørstavik [trans. from Norwegian by Martin Aitken] (2022)]. Original publication 2020. Norway.3

The Scent of Buenos Aires [stories], Hebe Uhart [trans. from Spanish by Maureen Shaughnessy (2019)]. Argentina.4

*A General Theory of Oblivion, José Eduardo Agualusa [trans. Portuguese by Daniel Hahn (2015)]. Original publication 2012. Angola. Shortlisted for Man Booker Prize. International Prize 2016. International Dublin Literary Award 2017.5

*Eastbound, Maylis de Kerangal [trans. from French by Jessica Moore (2023)].6 Original publication 2012. France.

Difficult Light, Tomás González [trans. from Spanish by Andrea Rosenberg (2020)]. Original publication 2011. Colombia.

The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu, Augusto Higa Oshiro [trans. from Spanish by Jennifer Shyue (2023)]. Original publication 2008. Peru

In the Presence of Absence, Mahmoud Darwish [trans. from Arabic by Sinan Antoon (2011)]. Original publication 2006. Palestine. National Translation Award 2012.

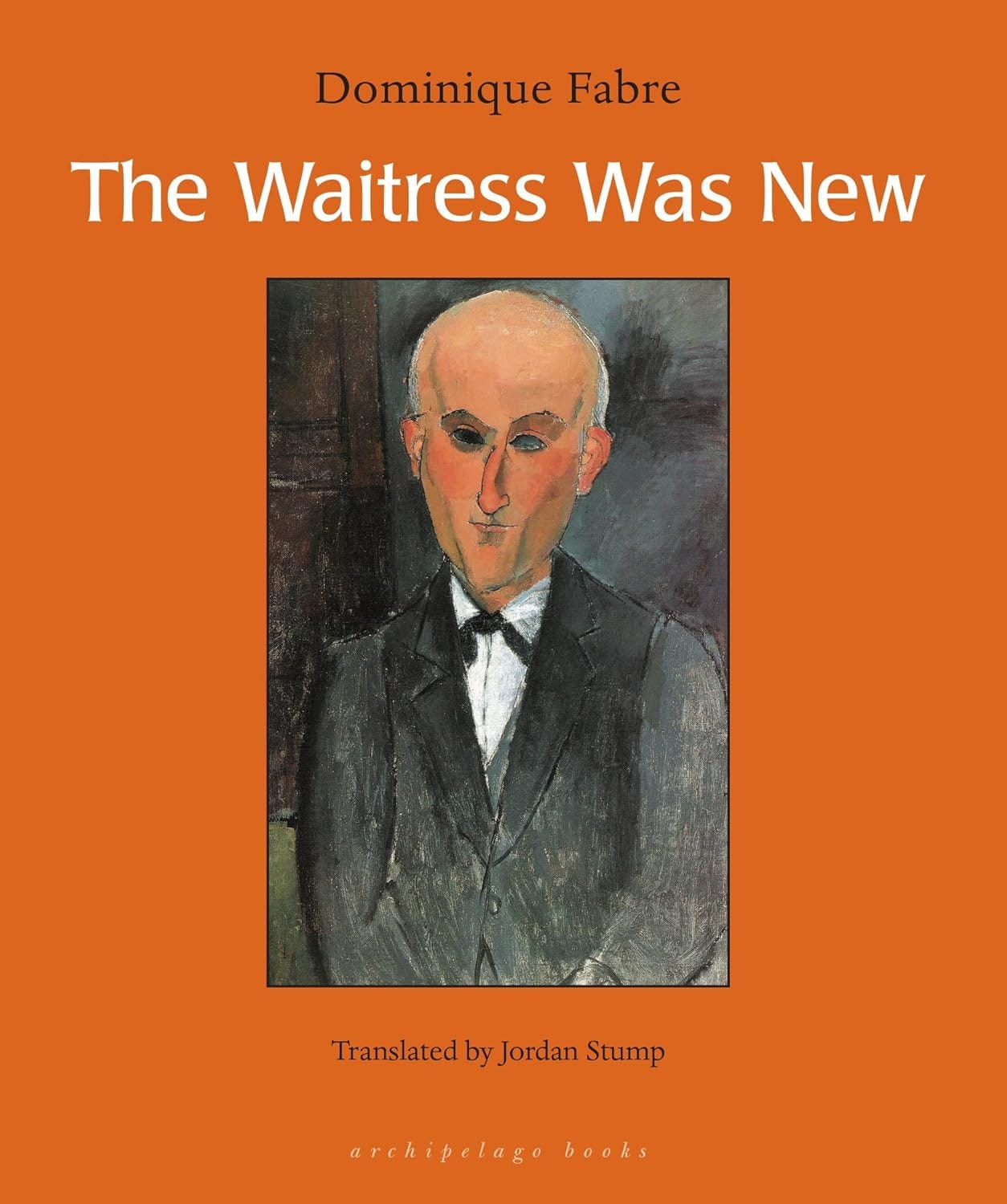

*The Waitress Was New, Dominique Fabre [trans. from French by Jordan Stump (2008)]. Original publication 2005. France.7

Moving Parts, Magdalena Tulli [trans. from Polish by Bill Johnston] (2005)]. Original publication 2005. Poland.

*Whale, Cheon Myeong-kwan [trans, from Korean by Chi-Young Kim (2023)]. Original publication 2004. South Korea.8

*A Time for Everything, Karl Ove Knausgaard [trans. from Norwegian by James Anderson (2009)]. Original publication 2004. Norway. 9

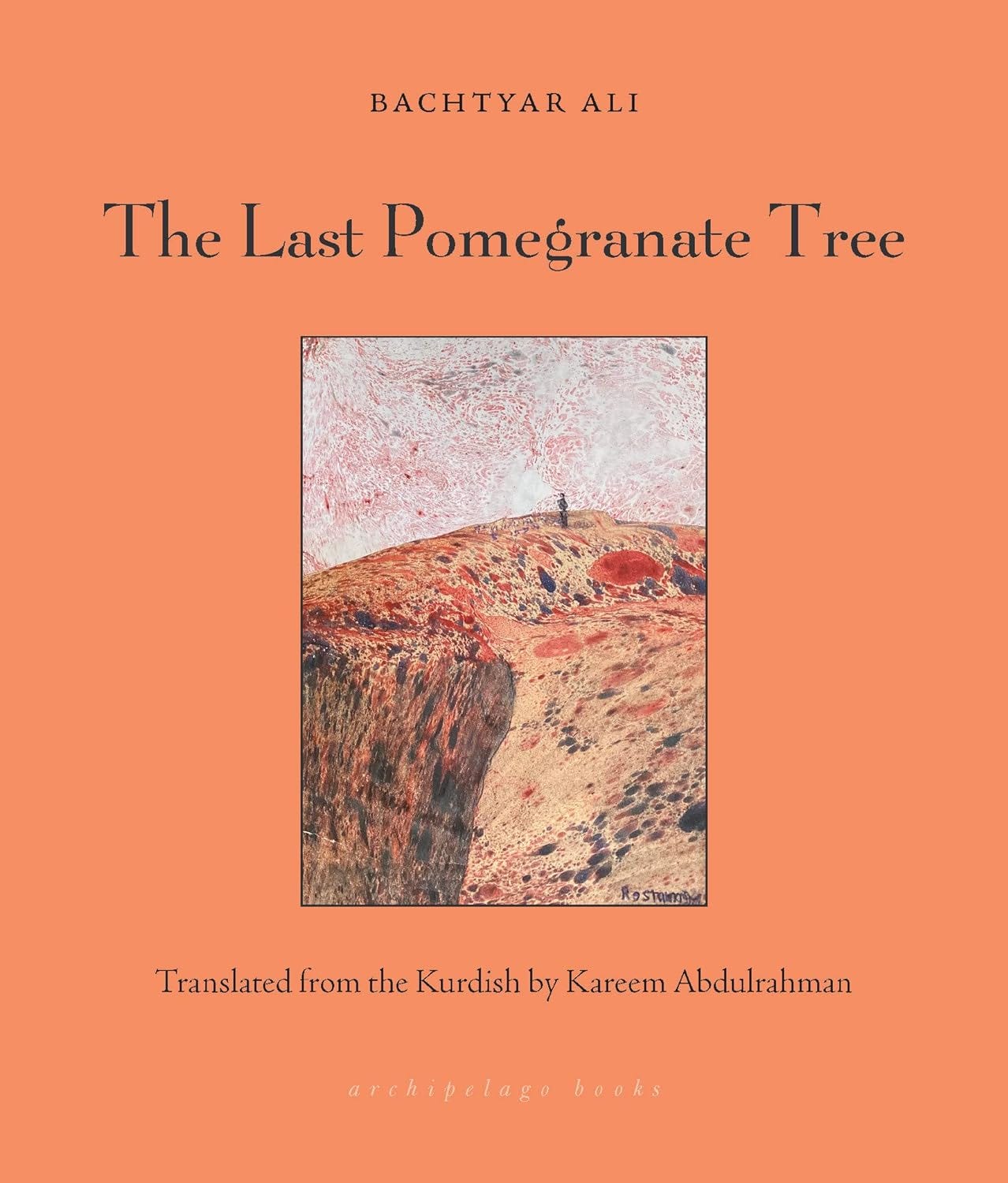

The Last Pomegranate Tree, Bachtyar Ali [trans. from Kurdish by Kareem Abdulrahman (2023)]. Original publication 2002. Iraq.

Gate of the Sun, Elias Khoury [trans. from Arabic by Humphrey Davies (2006)]. Original publication 1998. Lebanon. American Association of Publishers Best Book of the Year. A Best Book of the Year: San Francisco Chronicle, Christian Science Monitor. A Notable Book of the Year, New York Times.

Khoury died last month. Here’s his Wiki:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elias_Khoury

*Love, Hanne Ørstavik [trans. from Norwegian by Martin Aitken (2018)]. PEN Translation Prize 2019. Original publication 1997. Norway.10 Winner of the 2019 PEN Translation Prize, finalist for National Book Award.

Blinding, Mircea Cărtărescu [trans. from Romanian by Sean Cotter (2013)]. Original publication 1996. Romania

Autumn Rounds, Jacques Poulin [trans. from French by Sheila Fischman (2021)]. Original publication 1993. Canada/Quebec.

Moldy Strawberries [linked stories], Caio Fernando Abreu [trans. from Portuguese by Bruna Dantas Lobato (2022)]. Original publication 1982. Brazil.

*Dawn, Sevgi Soysal, [trans. from Turkish by Maureen Freely (2022)]. Original publication 1975. Turkey.11

Journal of an Ordinary Grief [autobiographical essays], Mahmoud Darwish [trans. from Arabic by Ibrahim Muhawi (2010)]. Original publication 1973. Palestine. PEN Translation Prize 2011.

*A Guardian Angel Recalls, W. F. Hermans [trans. from Dutch by David Colmer] (2021)]. Original publication 1971. Netherlands.

A Dream in Polar Fog, Yuri Rytkheu [trans. from Russian by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse] (2005) Original publication 1970. U.S.S.R./Russia/Siberia.

*January, Sara Gallardo, trans. from Spanish by Frances Riddle and Maureen Shaughnessy (2023)]. Original publication 1958. Argentina.

The Birds, Tarjei Vesaas [trans. from Norwegian by Michael Barnes and Torbjørn Støverud] (2016) Original publication 1957. Norway.

Salka Valka, Halldór Laxness [trans. from Icelandic by Philip Roughton] (2022)]. Original publication 1931-32. Iceland.12

The Project/Challenge:

Over the course of the next twelve months, read at least four Archipelago titles.

They can be any of those listed above (or in the footnotes), or any you find on their website—they’ve been around for twenty-plus years and have over 250 titles, in forty-some languages.

Even if you pick from my list, visit the website and poke around.

[In the case of Knausgaard’s, My Struggle, you can read the softcover reprints of the individual volumes (1-6) from FSG.]

Extra credit: Pick at least one book translated from a language (or country) you’ve never tried before.13

An interview with Jill Schoolman, Publisher of Archipelago Books:

https://lithub.com/interview-with-an-indie-press-archipelago-books/

[from LitHub, 25 June 2021]

Ørstavik: A woman caring for her husband at the end of his life. Sounds grim, I know, but it’s based on Ørstavik’s own experience. Sad, but not grim. She’s a very fine writer.

They’ve published several other of her slim novels including Love (1997) [see below].

Stay With Me will appear next spring.

https://archipelagobooks.org/book/stay-with-me/

Uhart: Just got A Question of Belonging (2024), a collection of short nonfiction pieces (published posthumously) called crònicas, with an introduction by Argentine novelist and story writer Mariana Enríquez. Original publication 2020.

Agualusa: Archipelago has published three of Agualusa’s works (all translated by Daniel Hahn). The other two: A Practical Guide to Levitation [stories] (Portuguese, 2005; English 2023) and The Society of Reluctant Dreamers (Portuguese 2017; English 2019). My intro to Agualusa was The Book of Chameleons, (Portuguese, 2004; English 2007), published in the U.S. by Simon & Schuster. The story of a dealer of “new pasts” told by a gecko (no, really). Recommended.

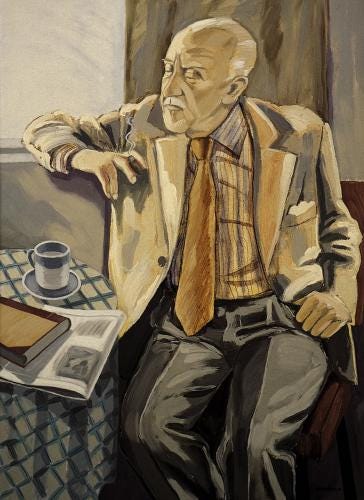

How can you not want to read something written by the guy behind this face??

Eastbound: Trans-Siberian train, a Russian conscript, an older French woman, Hélène who unexpectedly helps him desert. A slim, heartening read. Recommended.

https://bookshop.org/p/books/eastbound-maylis-de-kerangal/18648933?ean=9781953861504

And they’ve just published a small collection of stories, Canoes [2024]. Here’s a bit of their blurb:

Seven stories ricochet off of this exhilarating central novella, and in them we hear female voices by turns indelibly witty, insightful, intimate, bracing, and profoundly interconnected. The women of these stories are mad about: stones, molds of human jaws, voicemail recordings, sonic waves, UFOs, and always how the texture of human voice entwines with their obsessions. With cosmic harmonics, vivid imagery, and a revelatory composition, Canoes will leave its reader forever altered.

Fabre: I liked this book right away. It’s short and quite touching. Here’s what the press says:

Pierre is a veteran bartender in a café on the outskirts of Paris. When the café goes under, he is

at a loss for what to do next: at 56 years old, he’s too young for retirement and too weary to move

blithely on to another job. Pierre gains our trust immediately through his perceptive eye and

understated wit. As we follow his inner monologue over the course of three days, his sensitivity

and profound solitude are revealed. While a quiet book, the themes it brings into play are

immense: the terror of aging, the need for human contact (however superficial), and our

precarious dependence on forces beyond our control. The Waitress Was New is a moving

portrait of human anguish and weakness, of understated nobility and strength.Whale: This one snuck up on me. It’s a strange work; even the blurb at Archipelago doesn’t really describe it well. I ended up being quite taken with it. It’s one-of-a-kind. Give it a look.

Knausgaard: I ran into this around the time I was first reading his six-volume My Struggle. This is another hard-to-capture-in-a-nutshell novel.

Here’s Archipelago’s stab at it:

In the sixteenth century, Antinous Bellori, a boy of eleven, is lost in a dark forest and stumbles upon two glowing beings, one carrying a spear, the other a flaming torch . . . This event is decisive in Bellori’s life, and he thereafter devotes himself to the pursuit and study of angels, the intermediaries of the divine. Beginning in the Garden of Eden and soaring through to the present, A Time for Everything reimagines pivotal encounters between humans and angels: the glow of the cherubim watching over Eden; the profound love between Cain and Abel despite their differences; Lot’s shame in Sodom; Noah’s isolation before the flood; Ezekiel tied to his bed, prophesying ferociously; the death of Christ; and the emergence of sensual, mischievous cherubs in the seventeenth century. Incorporating and challenging tradition, legend, and the Apocrypha, these penetrating glimpses hazard chilling questions: can the nature of the divine undergo change, and can the immortal perish?

Ørstavik (again): This one has a gut-wrenching ending that I’m not going tell any more about.

https://bookshop.org/p/books/love-hanne-orstavik/9431423?ean=9780914671947

Dawn: This novel has appeared on earlier lists. It was published in Turkish in 1975, in English in 2022. There’s more about it at:

Halldór Laxness (1902-1998), Icelandic Nobel Laureate, 1955. Most of his readers (in English) start with Independent People (Icelandic, 1946; English, 1997) thanks to an over-the-top new introduction by Brad Leithauser. I know people who revere this novel; I found it tough sledding but plan to re-read it sometime after Salka Valka. I read another, Under the Glacier (Icelandic, 1968; English 2005)—generally, Laxness is not a barrel of laughs, but this one is—also, zany. It was adapted for film by his daughter, Guðný Halldórsdóttir, in 1968. Laxness was prolific—besides novels, he wrote poetry, nonfiction, plays, memoir, translated Hemingway into Icelandic, was politically active, traveled. His modern house outside Reykjavik is maintained as a museum (much as he left it, happily). I did a solitary walk-through in 2012, and found my own reverence for him.

[Portrait by Einar Hákonarson (1984)]

A language/country you’ve never tried:

This is how I found Congolese writer, Fiston Mwanza Mujila, Tram 83 (2014) and The Villain’s Dance (2020); Nino Haratischvili from Georgia, The Eighth Life (2014); Nawal el Saadawi from Egypt, Woman at Point Zero (1975); Andrzej Szczypiorski from Poland, The Beautiful Mrs. Siedenman (1986) and others.

A General Theory of Oblivion (which I admired more than I loved) features a brief poem which any writer should be able to relate to:

EXORCISM

I carve out verses

short

as prayers

words are

legions

of demons

expelled

I cut adverbs

pronouns

I spare my

wrists

I LOVE. LOVE. LOVE. Archipelago. I've been an ARC reviewer of theirs for years (although that does mean I miss out on the aesthetics of the hardbound books).