Nineteen Twenty-Five

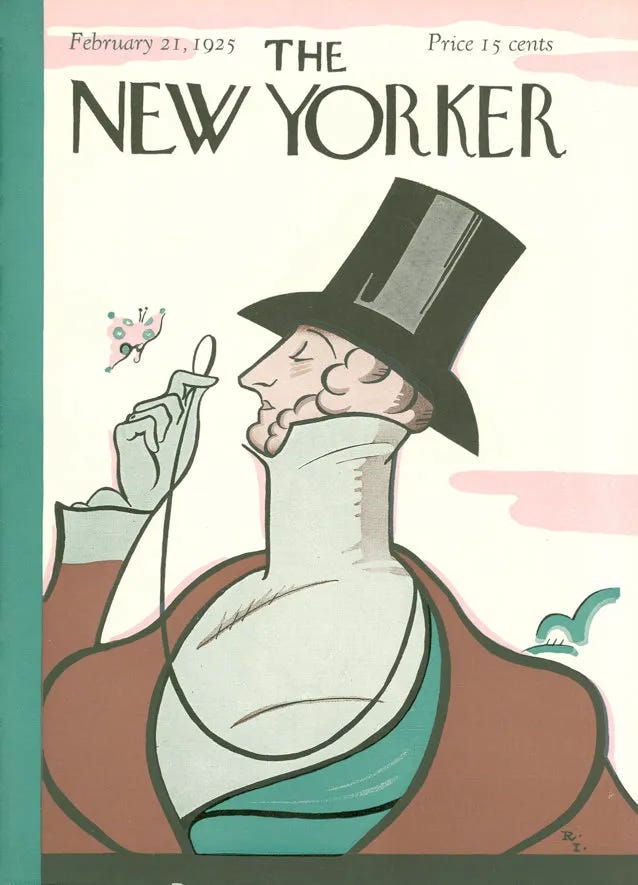

Silent Cal Coolidge1 was in the White House. Hitler published Mein Kampf, Mussolini (Il Duce) declared himself dictator of Italy. The first television picture was transmitted. High school teacher John Scopes was found guilty of teaching evolution and fined $100.2 The Geneva Protocol banned chemical and biological weapons. The Grand Ole Opry premiered. Paul Newman, Flannery O’Connor, Yogi Berra, and Malcolm X were born. John Singer Sargent, Erik Satie, and Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson died. George Bernard Shaw was given the Nobel Prize in Literature, Edna Ferber (So Big) the Pulitzer. But of course the key event of 1925 took place on February 21st: the inaugural issue of The New Yorker.

Wikipedia lists eighty-seven works of fiction published in 1925. But if you search for first editions of 1925 novels at, say, AbeBooks.com, you find close to a thousand—even accounting for duplicates, it’s clear that many titles fell through Wiki’s sieve. I have mixed feelings about this fact. The writerly/archivist side of me rankles (remembering the day, a few years back, when I found that my novels and books of stories had been culled from the shelves and catalog of the Seattle Public Library System). Yet, as a householder and observer of how the world operates, I know a core truth: You can’t keep everything.

Working on the Birth Year Project posts, I’ve seen, too, that while great books are published every year, some years—1925 being one—are like the pools under waterfalls where gold nuggets collect. Some years seem uniquely positioned in history—in the aftermath of national/world events, or radical swerves in the zeitgeist. Anyone who keeps track of what they’ve read will notice these banner years cropping up now and then.3

Today’s post honors the works of 1925, and at the end you’ll find a challenge.

As always, I encourage you to read this post on your laptop, and to dive into the footnotes (where the meat is), and to visit some of the links. Imagine my happiness at the thought of you getting the poop on a writer you didn’t know before. Suh-weet!]

The Books

1. Seven Biggies:

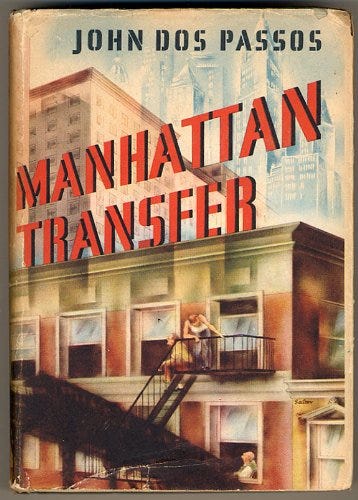

Manhattan Transfer, John Dos Passos4

An American Tragedy, Theodore Dreiser

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

In Our Time [stories], Ernest Hemingway

Arrowsmith, Sinclair Lewis

The Painted Veil, W. Somerset Maugham

Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf

2. Eight Less-Remembered Novels:

Dark Laughter, Sherwood Anderson5

The Professor's House, Willa Cather6

Pastors and Masters, Ivy Compton-Burnett7

Sorrell and Son, Warwick Deeping8

Barren Ground, Ellen Glasgow9

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Anita Loos10

The Making of Americans, Gertrude Stein11

Carry On, Jeeves, P. G. Wodehouse12

3. Eleven Works of World Lit:

A Young Doctor's Notebook and The Fatal Eggs, Mihail Bulgakov13 [Russia]

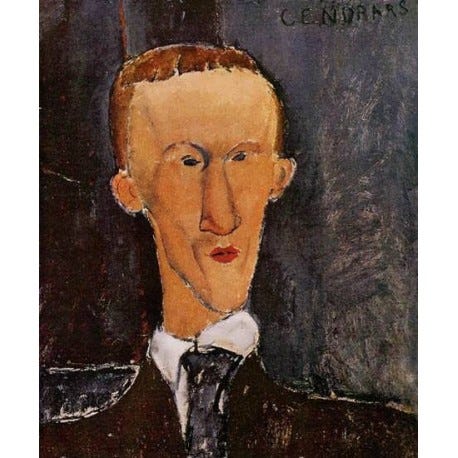

Gold: The Marvelous History of General John Augustus Sutter, Blaise Cendrars14 [France]

[Modigliani portrait of Cendrars]

The Madonna of the Sleeping-Cars, Maurice Dekobra15 [France]

The Counterfeiters, Andre Gide16 [France]

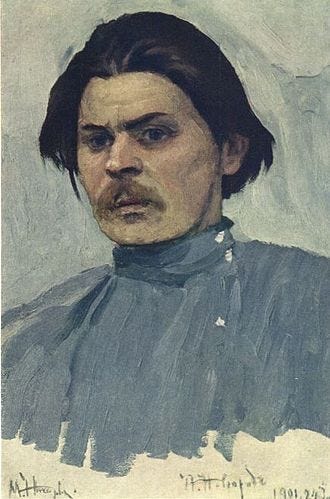

The Artamonov Business, Maxim Gorky17 [Russia/Soviet Union]

Chaka, Thomas Mofolo18 [Lesotho]

The Informer, Liam O'Flaherty19 [Ireland]

Turbott Wolfe, William Plomer20 [South Africa/England]

Albertine Disparue, Marcel Proust21 [France]

From the Marsh of the Hills: Nine Short Stories, Kate Roberts22 [Wales]

Metropolis, Thea von Harbou23 [Germany]

4. Seven Rediscoveries:

Replenishing Jessica, Maxwell Bodenheim24

The Polyglots, William Gerhardie25

Simonetta Perkins [novella], L.P. Hartley26

Wild Geese, Martha Ostenso27

The Wind, Dorothy Scarborough28

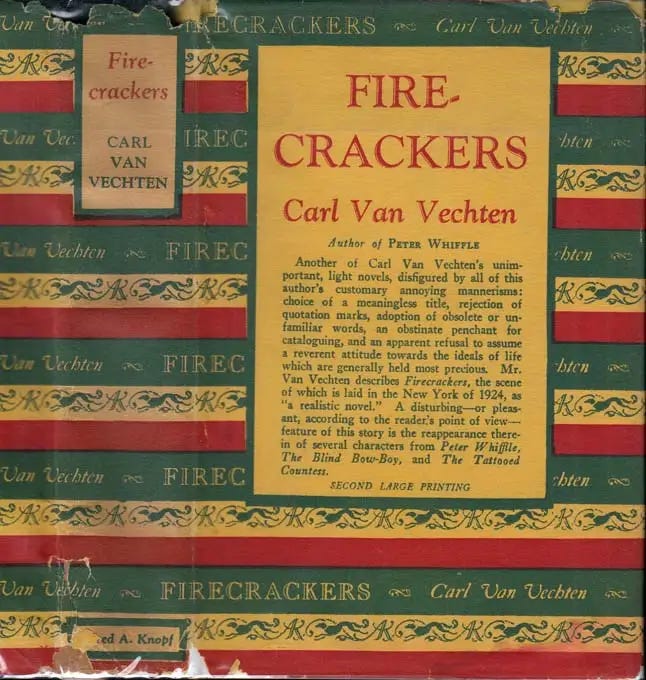

Firecrackers, Carl Van Vechten 29

5. Five Lesser books by well-known authors:

The Crystal Cup, Gertrude Atherton30

Those Barren Leaves, Aldous Huxley

The Keeper of the Bees, Gene Stratton-Porter 31

Christina Alberta's Father, H. G. Wells 32

The Mother's Recompense, Edith Wharton (1925)33

6. A Dozen to Research on Your Own:

Drums, James Boyd34

The Haven, Dale Collins

The Sailor's Return, David Garnett

Jaqo's Dispossessed, Mikheil Javakhishvili35

The Free Lovers: A Novel of To-day, Reginald Wright Kauffman36

The Black Cargo, Marquand, J. P. Author's third book. A novel of the illicit slave trade in New England on a clipper ship.

Mockery Gap, T. F. Powys37

Neutopia, Edith Richardson38

The Immortal Girl, Berta Ruck39

The Vow of Micah Jordan, Una Lucy Silberrad

The Rector of Wyck, May Sinclair40

Taboo, Wilbur Daniel Steele41

Portrait of a Man with Red Hair, Hugh Walpole42

A Link:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2015/mar/11/was-1925-really-the-best-year-for-literature

The Reading Project:

As with this project’s seventeen older siblings, we pretend you’re in desperate need of a new structured-reading challenge, and I say, Terrific, I just so happen to have one right here!

The Rules: In honor of this Hundredth Anniversary, read ten books from today’s post, one per month, at least one from each of the six mini-lists. Two of the books must be by writers you’ve never heard of.

Substitutions:

One book can be a re-read.

One book can be a second book by one of the writers you’ve already read (in the challenge).

One book can be a book found in the footnotes.

Extra credit [1]: Read Manhattan Transfer and copy out some sentences as nifty as the one I quoted.43

Extra credit [2]: Write a guest post about the experience of tackling this challenge.

Extra credit [3]: Google the Table of Contents of The New Yorker’s first issue, then read a work by one of those writers.

Coolidge: A former governor of Massachusetts, he’d been Harding’s Veep, and assumed office on Harding’s sudden death in 1923. Harding had been a popular president—only later was his image tarred by his extramarital affairs and the corruption of the Teapot Dome Scandal.

Scopes: The “Monkey Trial” (so named by H. L. Mencken), one of the most renowned court cases in U. S. history: Clarence Darrow for the ACLU, William Jennings Bryan for the State of Tennessee. The conviction was overturned on appeal.

Banner years: But also: your list represents your choices—some years you’ve dug deeper in a certain vein (say, American ex-pats after WWI and before the Crash), whereas others, scant-seeming, may result from your having missed a wealth of writing beyond the boundaries of your awareness (say the Latin American Boom), or your taste.

Dos Passos: I’ve never read the project he’s famous for, the U.S.A. Trilogy: The 42nd Parallel (1930), Nineteen Nineteen (1932), and The Big Money (1936).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S.A._(trilogy)

But Manhattan Transfer is a feast of great writing.

I’ve quoted from it in earlier posts (on language, surprise, and sentence-writing audacity)—on the off-chance you missed it, here’s an entry from my Audacious Sentence Hall of Fame:

She stood in the middle of the street waiting for the uptown car. An occasional taxi whizzed by her. From the river on the warm wind came the long moan of a steamboat whistle. In the pit inside her thousands of gnomes where building tall brittle glittering towers.

Anderson:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_Laughter

Cather:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willa_Cather

Compton-Burnett: Prolific, Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE), a self-described "fierce Victorian atheist," spent her life with Margaret Jourdain (an authority on decorative arts).

A note from her Wiki page:

. . . [she] developed a highly individualistic style. Her fiction relies heavily on formal dialogue . . . and demands constant attention on the reader's part: there are instances in her work where important information is casually mentioned in a half sentence, and her use of punctuation is deliberately perfunctory. The result is to create a deliberately claustrophobic fictional world, dominated by the psychological exploration of small-scale power-abuse and persecution.

Deeping: A best-selling English novelist in the 1920s. Prolific, middle-brow (disdained by heavyweight contemporaries). Also a doctor—he and Bulgakov and Stein (who’d been a medical student) will be in a forthcoming post on medical doctors who wrote literary fiction.

Glasgow: Should not be forgotten, winner of 1942 Pulitzer for In This Our Life.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ellen_Glasgow

Loos: I was excited to read this a few years ago—Jazz Age shenanigans, source of the Howard Hawks film of the same name (1953)—Jane Russell, Marilyn Monroe. Loos was the first female staff screenwriter in Hollywood. To be honest, I didn’t think it was all that terrific. Oh well.

Stein:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Making_of_Americans

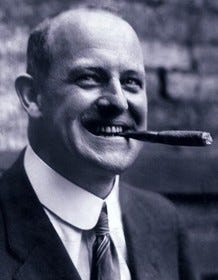

Wodehouse: If you’re a Jeeves and Wooster virgin, check out the TV series from the early 90s—Hugh Laurie (the feckless young Bertie Wooster) and Stephen Frye (his deadpan, long-suffering valet who routinely hauls Bertie’s fat from the fire).

The https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeeves_and_Wooster

How well do the novels hold up? They’re still a hoot at times—making fun of clueless aristocrats never truly goes out of style (a few years ago I read Juvenal’s Satires (c. 100-127 CE) and happily discovered that what the ancient Romans thought was funny, we still do). Of the handful of Wodehouses I’ve read, Right Ho, Jeeves (1934) is funniest. You have to be in the right mood. He also wrote a four-book series featuring the monocled dandy, Rupert Psmith (the “P” is silent, he explains, “as in pshrimp”). Wodehouse was knighted a month before his death in 1975.

[P. G. Wodehouse]

Bulgakov: Writer, medical doctor, playwright. Best known for his novel The Master and Margarita, published posthumously, considered one of the masterpieces of the 20th C. fiction.

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2012/dec/04/young-doctors-notebook-hamm-radcliffe

Cendrars: This novel is remembered mainly because it was the source of the 1936 Western Sutter’s Gold, the screenplay for which was written by William Faulkner. Sutter’s discovery of gold set of the California Gold Rush, but the last part of his life is a sad tale.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Sutter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blaise_Cendrars

Dekobra:

https://www.amazon.com/Madonna-Sleeping-Cars-Neversink/dp/1612190588

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/91812.Maurice_Dekobra

Gide:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Counterfeiters_(novel)

Mofolo:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaka_(novel)

O’Flaherty: I read this slim novel last year, a gritty portrait of the Irish Civil War.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Informer_(novel)

Plomer:

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Turbott_Wolfe/2d3BAAAAIAAJ?hl=en

Proust: Volume Six of the seven-part In Search of Lost Time aka Remembrance of Things Past [original title: À la recherche du temps perdu].

From Wiki, explaining the title:

The final three volumes of the novel were published posthumously and without Proust's final corrections and revisions. The first edition, based on Proust's manuscript, was published as Albertine disparue to prevent it from being confused with Rabindranath Tagore's La Fugitive (1921). The first definitive edition of the novel in French (1954), also based on Proust's manuscript, used the title La Fugitive. The second, even-more-definitive French edition (1987–89) uses the title Albertine disparue and is based on an unmarked typescript acquired in 1962 by the Bibliothèque Nationale.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albertine_disparue

Roberts:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kate_Roberts

von Harbou:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metropolis_(novel)

Bodenheim: One of the pieces on Bodenheim begins:

When the poet Maxwell Bodenheim and his common-law wife, Ruth Fagan, were found brutally murdered by the insane man whose single room they were sharing, the press made much of the sensation.

Blurb for Replenishing Jessica lifted from I can’t remember where: One time scandalous bohemian novel by Greenwich village eccentric. Though rather tame by today's standards, Bodenheim's novel about a sexually promiscuous young woman was a scandal at the time of publication, bringing obscenity charges against his publisher Horace Liveright in a much publicized case. Jessica's story is 99 years old now but is still spry for its age.

https://newyorkerstateofmind.com/tag/replenishing-jessica/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maxwell_Bodenheim

Gerhardie:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Gerhardie

Hartley: Known in our day for The Go-Between (1953)—filmed in 1971 [Alan Bates, Julie Christie]—also the Eustace and Hilda Trilogy (1944–1947). English, prolific, highly regarded.

Wiki on Simonetta Perkins:

Young American ingénue, Lavinia Johnstone, is vacationing in Venice with her overbearing mother. She has recently refused four estimable suitors presented to her in Boston by her hopeful parents. Through her alter ego, Simonetta Perkins, Lavinia commits to her diary her secret feelings for handsome gondolier, Emilio. Will Miss Perkins resist temptation?

Ostenso: Norwegian-born/Canadian writer, later a naturalized American. Wild Geese (a young school teacher in rural Manitoba) is considered “a landmark in Canadian realism.” It has been filmed several times over the years.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martha_Ostenso

Scarborough: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_Scarborough

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b312460&seq=1

Van Vechten: Writer and photographer—especially of the Harlem Renaissance [see Reading Project [13]:

https://longd.substack.com/p/reading-projects-13-the-harlem-renaissance

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/van/biography.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firecrackers_(novel)

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/02/17/white-mischief-2

Atherton:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gertrude_Atherton

Stratton-Porter: Most readers know her for A Girl of the Limberlost (1909), but she was also an ardent naturalist/conservationist, and a pioneer of women’s film production.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_Stratton-Porter

Wells: We tend to forget that Wells didn’t limit himself to speculative fiction—The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), When the Sleeper Wakes (1899), etc., but wrote “straight” novels as well, including satire/social comedy—Tono-Bungay (1909), The History of Mr. Polly (1910)—and a “New Woman” novel, Ann Veronica (1909). He was amazingly prolific—fifty novels, scads of short stories, and major works of nonfiction.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christina_Alberta%27s_Father

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._G._Wells

Wharton:

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/720238.The_Mother_s_Recompense

https://www.themodernnovel.org/americas/other-americas/usa/wharton/mother/

https://www.virago.co.uk/titles/edith-wharton/the-mothers-recompense/9781844083619/

Drums: Revolutionary War.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Boyd_(novelist)

Mikheil Javakhishvili: Jaqo's Dispossessed may not be available in English, but his 1924 novel, Kvachi, is. Javakhishvili was a a major figure in Georgian literature. His work was condemned by the Soviet state—in 1937 he was arrested, tortured, then executed, along with his brother, his wife exiled. His reputation was rehabilitated in the 1950s.

A blurb for Kvachi:

This is, in brief, the story of a swindler, a Georgian Felix Krull, or perhaps a cynical Don Quixote, named Kvachi Kvachantiradze: womanizer, cheat, perpetrator of insurance fraud, bank-robber, associate of Rasputin, filmmaker, revolutionary, and pimp. Though originally denounced as pornographic, Kvachi's tale is one of the great classics of twentieth-century Georgian literature--and a hilarious romp to boot.

The Free Lovers: Young couple flee the restrictive social environment of their small town, get hammered on the train to NYC, wake up the next day and discover they've gotten married. They've been so vocal about not believing in marriage, they’re forced to live in Greenwich Village, keeping the marriage on the down low, appearing to be cohabiting, having a "free" relationship.

https://www.readinkbooks.com/product/22071/The-Free-Lovers-A-Novel-of-To-day

Mockery Gap: From the New Statesman:

[His] . . . novels and short stories are set in a landscape as far removed as possible from anything smart or urban - a fantastical version of English village life. . . . He sets his tales in a grotesquely exaggerated rural landscape, not because he has any nostalgia for the way of life it may once have contained, but because, by doing so, he is free to strip human beings down to their barest elements - their lust, greed, cruelty and stupidity, and the mixture of dread and yearning with which they respond to the prospect of death."

Hmm. Not sure I’m sold on this one . . .

Neutopia: Novel about the discovery of a utopian lost race, with advanced science and technology."

Ruck:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berta_Ruck

Sinclair:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_Sinclair

Steele: Romance exploring racial taboos.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilbur_Daniel_Steele]

Walpole:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Walpole

Extra credit/Manhattan Transfer: A couple more:

A car whirred across the bridge making the girders rattle and the spiderwork of cables thrum like a shaken banjo.

“Say Anna,” says a broadhipped blond girl . . . “did ye see that sap was dancin wid me? . . .He says to me the sap he says See you later an I says to him the sap I says see yez in hell foist . . . an then he says, Goily he says . . .”

Two of these, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and The Counterfeiters, are group reads this year on Read the Classics with Henry Eliot, if anyone accepting your challenge would like some company.