NOTES:

Here’s a meaty one for you today.

I’ll be off-grid until after Labor Day—next post second week of September.

If you’re a newish subscriber/follower:

I really appreciate your attention amid the frenetic assault on your head space.

Thank you!

The posts on David’s Lists 2.0 are often much longer, and take greater concentration, than on some Substacks—the more diary/journal/personal history sort. I mean mine to be an ongoing resource for your reading lives; I’ve numbered the posts that are part of a series—Birth Year Project, Sixes, Reading Projects—to make it simple to flip back to earlier ones.

I’ve (mostly) come to terms with Substack’s formatting issues, but if you read the posts directly from your email, you’re not seeing what I see. They’re best read on a laptop, but short of that, try to open them at Substack.

Some of you have offered $$$ for this content. I appreciate it, absolutely. But, this Substack is free, and always will be. Buy a book instead? Or talk some of your estimable friends into subscribing . . .

Since I guess I’m retired from fiction making, making these posts feels like a reasonable use of my time—the detail-work, as Lennon/McCartney once put it, keeps my mind from wandering. And passing on what I’ve learned (as I’ve told some of you privately) feels like what the Buddhists call right livelihood.

Onward.

The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond

Before Marlon James and James McBride and Zadie Smith and Tayari Jones and Walter Mosely and Jamaica Kincaid and Terry McMillan and Gloria Naylor . . . before N. K. Jemisin, Oyinkan Braithewaite, Lesley Nneke Arimah, Nnedi Okorafor, Nalo Hopkinson, and a wealth of others . . . there were the giants of mid- to late-20th century: Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Octavia Butler, Alice Walker, Ishmael Reed, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, and so on . . . Since this Substack is about fiction/fiction writers I’ve left out the poets and nonfiction writers (though some of today’s writers have published memoirs, essay collections, plays, manifestos, and other hard-to-slot writings). Also, for reasons of space (and my ignorance), I’m omitting (for now) most of the Caribbean/West Indian writers—Jean Rhys, Sam Selvon, George Lamming, Caryl Philips, Kamau Braithwaite, et al.

Most of you have read novels by most of the writers named above—Sula and Beloved, The Color Purple, The Invisible Man, Native Son, Kindred, Parable of the Sower, The Fire Next Time, White Teeth, A Brief History of Seven Killings, The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, An American Marriage . . .

But, as usual, those aren’t the books we’re focusing on today.

The novels below are a small gathering of the other books, within the time-frame of the Harlem Renaissance (usually considered to be the 1920s/early 1930s), but mostly in the years afterward, some having no direct connection to that movement. Some of these writers—Ann Petry, for instance—have a well-known novel (The Street, 1946), so I’ve included her less-often-read The Narrows. [Ditto for Nella Larsen—Quicksand rather than Passing (1929)]. Some are high-brow, some pulpy, some sci-fi. Some are early novels by writers we know from work later in the century.

The Books:

Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick: Stories from the Harlem Renaissance, Zora Neale Hurston (2020)1

Trick Baby: The Story of a White Negro, Iceberg Slim (1967)2

A Glance Away, John Edgar Wideman (1967)3

Babel-17, Samuel R. Delaney (1966)4

The Learning Tree, Gordon Parks (1963)5

A Different Drummer, William Melvin Kelley (1962)6

Brown Girl, Brownstones, Paula Marshall (1959)7

Youngblood, John Oliver Killens (1954)8

Maud Martha, Gwendolyn Brooks (1953)9

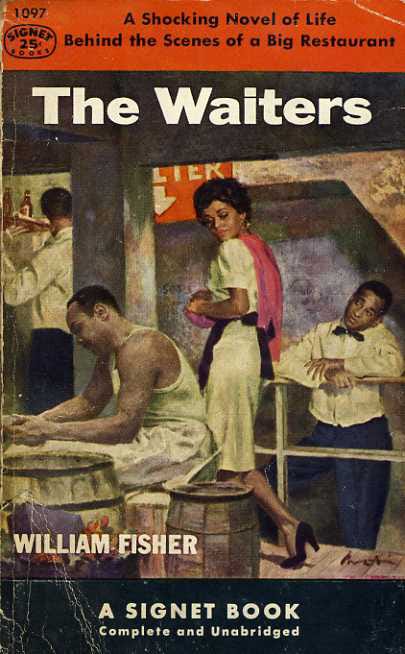

The Waiters, William Fisher (1953)10

The Narrows, Ann Petry (1953)11

A Woman Called Fancy, Frank Yerby (1951)12

The Living is Easy, Dorothy West (1948)13

If He Hollers Let Him Go, Chester Himes (1945)14

Blood on the Forge, William Attaway (1941)15

The Ways of White Folks [short stories], Langston Hughes (1934)16

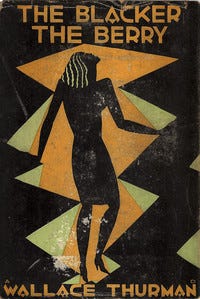

The Blacker the Berry, Wallace Thurman (1929)17

Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral, Jessie Redmon Fauset (1928)18

Quicksand, Nella Larsen (1928)19

Home to Harlem, Claude McKay (1928)20

Flight, Walter White (1926)21

When Washington Was in Vogue, Edward Christopher Williams (1925-26)22

Cane, Jean Toomer (1923)23

The Project/Challenge:

Most of us read new (or newish) books. Most of us read books that correspond to our own gender, sexual orientation, country of origin, time of life, geographic frame of reference, and so on. We are birds who like our own flocks.

The opposite is also true.

Sometimes we read away from our tribe—because we’re curious, because we’re sick of our own squint at things, and perhaps because we feel a moral compulsion to stop seeing our tribe as the only true center of the cosmos . . . or simply because a writer from a different tribe wrote a terrific book and we’d be idiots not to read it.

Most of you are white, and my guess is that the majority of the titles in today’s post are new to you—even if, like me, you’re an avid reader of, say, Zadie Smith and Toni Morrison and James McBride and Walter Mosely, et al.

The challenge:

In the next twelve months, read five of these works--or any other books by these writers (or books cited on the Biblio.com pages). A few may be hard to come by . . . but not impossible.

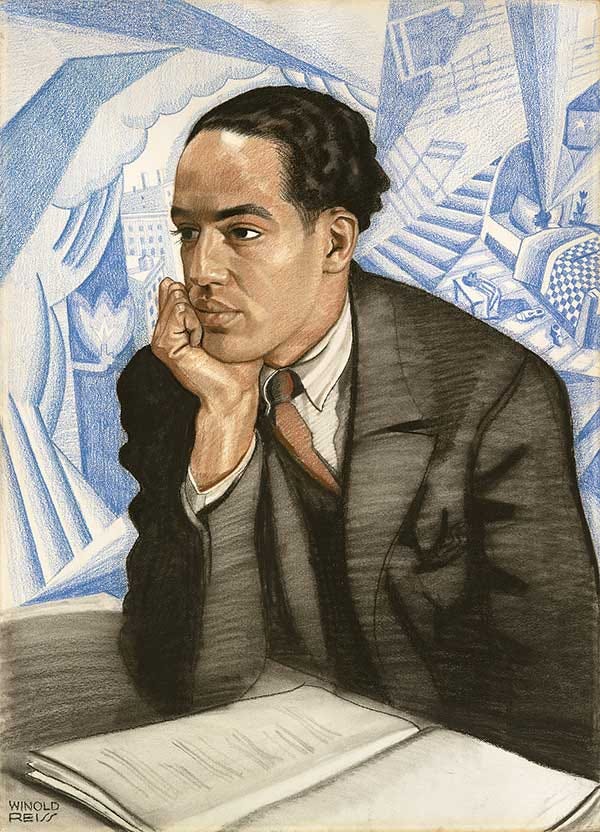

Langston Hughes (1902–1967) by Winold Reiss (1886–1953), ca. 1925. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Instituation.

A Few Harlem Renaissance Links:

https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/new-african-american-identity-harlem-renaissance

https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/harlem-renaissance

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harlem_Renaissance

https://www.loa.org/books/350-harlem-renaissance-novels-boxed-set/

https://www.loa.org/books/352-harlem-renaissance-five-novels-of-the-1920s/

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/19/arts/harlem-renaissance-librarians-libraries-books-literature.html

https://electricliterature.com/theres-a-harlem-renaissance-resurgence-happening-in-2018/

https://bookshop.org/p/books/women-of-the-harlem-renaissance-marissa-constantinou/15915889?ean=9781529069228

NOTE: Biblio.com was a major resource for this week’s post. Here, by way of example, is their page for the 1930s:

https://www.biblio.com/book-collecting/by-year/african-american-lit/1930-1939

Hurston: Her 1937 novel, Their Eyes Were Searching God, tempted me to list her with the other “giants” . . . but her wide renown came late in the game, spurred by the likes of Alice Walker, and later Henry Louis Gates, Jr. I’m including this recent collection because a) the work dates to the Harlem Renaissance, and b) the foreword is by novelist Tayari Jones [An American Marriage, 2019]. Also: You really should read Hurston’s Wiki to understand her story—her unorthodox views, the breadth of her creative work, the arc of her fall into, and emergence from, obscurity:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zora_Neale_HurstonIceberg: Oh, boy, what to say about this gentleman? Well, if you visit his Wiki, you’ll notice that under “Occupation(s)” it says: pimp, author. And there’s the part about spending ten months in solitary confinement. But I don’t want to spoil it for you . . .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iceberg_Slim

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-fires-that-forged-iceberg-slim

Oh, and: Wiki cautions us not to confuse this Iceberg Slim with the Iceberg Slim who’s a Nigerian hip-hop musician . . . or, for that matter, with the British rapper, Iceberg Slimm.

Wideman: Again, I was guided in picking today’s titles by Biblio.com. It’s a rich resource—but it’s good to remember their focus is book collecting. Here’s their note on Wideman’s novel:

A Glance Away is John Edgar Wideman’s first novel, published when he was 26 years old. Two characters, Eddie Lawson, a young African American, and Robert Thurley, a white professor, are linked through ‘Brother’ - a drug-dealing friend of Eddie’s trying to lure him back to drugs, and the lover of the aging and confused Thurley. The action unfolds over the course of a day as the men try to save themselves from their demons. The New York Times Book Review raved "Here is a novelist of high seriousness and depth. He has all sorts of literary gifts, including a poet's flair for a taut, meaningful, emotional language."

https://www.biblio.com/book-collecting/by-year/african-american-lit/1960-1969Delaney:

Dedicated readers of this Substack will (maybe) recall that Delaney appeared in an earlier post: https://longd.substack.com/p/reading-projects-3-big-hard-novels. The big hard novel was Dhalgren (1975). Babel-17, his seventh novel, came almost a decade earlier.

If you’ve spent any time poking about in mid- to late-century sci-fi lists, you know Delany’s name—in the company of Heinlein, Bradbury, Herbert, Asimov, Clarke, Bester, Blish, Pohl, Wyndham, Ballard, Dick, Lem, Brunner, Niven, Aldiss, and a slew of others (including so-called literary types who wrote one or two on the side, or started in the sci-fi camp like Vonnegut, or novelists like Le Guin and Lessing who were essentially literary writers whose work involved alt-world building. Sci-fi, at the time, was a white boy’s playground, but as the century progressed, then became our era, the territory where sci-fi shades into what’s (clumsily, to my mind) called fantasy, is rife with Black women writers—Octavia Butler, Nalo Hokinson, Nnendi Okorafor, N. K. Jemisin, Tananarive Due . . . GoodReads has a list labeled Black Women in Science Fiction with 242 entries.

Anyway, Delaney is still at it, age 82, a prolific, widely read and praised. Babel-17 was co-winner of the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 1967 (with Flowers for Algernon).

Parks: In the mid-1980s, I took a deep dive into the iconic photos of the American Dust Bowl/Great Depression. I talked about this in an earlier post:

Gordon Parks was the lone Black man in the cohort of photographers hired, initially, to document the New Deal’s efforts to combat rural poverty during the Great Depression. Among others in the group: Dorothea Lange, Marion Post Wolcott, Arthur Rothstein, and Walker Evans [Evans later made the photographs that accompany James Agee’s text in Now Let Us Praise Famous Men (1941)]. Not only is that an amazing work, the story of its creation is worth checking out—you can start with the Wiki about Agee:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_AgeeAnyway, I wasn’t surprised that Parks wrote a novel. He also composed music, and wrote and directed movies including the 1969 adaptation of The Learning Tree (the first major-studio production directed by an African-American, and one of the first 25 films chosen for the United States National Film Registry.

Kelley:

Kelley’s first novel. The premise: All the Black people suddenly disappear from a Southern state. Narrated by a roster of white characters. Here’s his Wiki:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Melvin_Kelley

I first read Kelley in a seminal short story anthology, New Sounds in American Fiction, Gordon Lish, ed. (1969). It also has Grace Paley, Donald Barthelme, Stanley Elkin, James Purdy and bunch of others you might not recognize. Kelley’s story is “Not Exactly Lena Horne.” But I treasure this book because it’s where I found one of my Hall of Fame stories, “The Last Running” by John Graves (which was otherwise hard to come by). You can access it at:

https://archive.org/details/newsoundsinameri0000gord/page/n5/mode/2up

Also, a few years back, The New Yorker ran a piece on Kelley called “The Lost Giant of American Literature”:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/29/the-lost-giant-of-american-literature

Marshall: Marshall’s debut novel. A coming-of-age story set in the Brooklyn of the 30s and WWII eras. Young woman dealing with the dissonance between the visions of her mother and Barbados-born father. Marshall was awarded a Guggenheim, was a MacArthur Fellow, won the Dos Passos Prize for Literature. She may be best known for her novel Praisesong for the Widow (1983)—reprinted by McSweeney’s in 2021, part of their Of the Diaspora series.

Killens: A founding member of the Harlem Writers Guild. Youngblood follows a Georgia family through the opening decades of the 20th C. It was Killens’ first novel, and was nominated for a Pulitzer. It came to be an important work for the Civil Rights Movement.

Brooks: Known as a major mid-century poet. Synonymous with Chicago, Pulitzer winner in 1949 (for Annie Allen), awardee of fifty-some honorary degrees. A string of sentences in her bio begin, “First Black woman to . . .” If you were at all into poetry you knew her rhythmic gut-punch of a poem, “We Real Cool.”

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/28112/we-real-coolIn thirty-four vignettes, Maud Martha traces a young Black girl coming of age in 1920s. It was Brooks’ only novel.

Petry: The Street was the first novel by a Black woman to sell a million copies. In The Saturday Review of Literature, Arna Bontemps wrote:

A novel about Negroes by a Negro novelist, and concerned, in the last analysis, with racial conflict, the novel somehow resists classification as a “Negro novel,” as contradictory as that may sound. In this respect, Ann Petry has achieved something as rare as it is commendable. Her book reads like a New England novel, and an especially gripping one.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ann_Petry

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/441024Yerby: From Biblio.com:

A Woman Called Fancy is Frank Yerby's first novel to have a female protagonist, Fancy, who rises from poverty to prominence among the wealthy aristocrats of Augusta, Georgia in the late 19th century. Yerby left the United States shortly after the publication of A Woman Called Fancy and first moved to France, then Spain, spending the rest of his life abroad in a protest against racial discrimination in the United States. During his lifetime Yerby wrote a total of thirty-three novels. A Woman Called Fancy was his sixth.

West: Her debut novel. West is heavily associated with the Harlem Renaissance and knew many of the era’s other writers—she and Langston Hughes spent a year in Russia making a film about race relations (it was not released). From 1934-1937 West published the magazine Challenge. The Living is Easy follows a young Southern girl’s quest for an upper-class lifestyle. It was brought back into print in 1982 by The Feminist Press.

Himes: Among his other writings was a series of Harlem detective novels, including Cotton Comes to Harlem (1964), filmed in 1970, Ossie Davis directing. In 2011 and 2020 Penguin Modern Classics brought out five of the Harlem cycle novels.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chester_Himes

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/02/books/review/chester-himes-essential-harlem-detectives.html

Attaway:

The 1953 Popular Library paperback described Blood on the Forge as “A savage, realistic novel of twisted passions and naked violence set against the bleak and brutal background of the booming steel towns of Pennsylvania.”

Considered a proletarian novel of the Great Migration, it highlights the struggles of African American men trying to earn a living in America by following the story of three men from rural Kentucky to industrial Pittsburgh, and their lives set against the labor movements within the Steel industry. The novel is set in 1919, at a time after WWI when the mass migration from the rural South to the Industrial North began. Blood on the Forge was Attaway’s second and last novel. It was well-received critically but didn’t attain the success of similar radical Depression-era novels like Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath and Wright’s Native Son.

Hughes: Perhaps the central-most figure of the Harlem Renaissance, remembered today mainly as a poet though he wrote widely—fiction, essays, criticism/commentary—edited anthologies, wrote a play (with Zora Neal Hurston), and so on.

https://poets.org/poet/langston-hughes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langston_Hughes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langston_Hughes_Society

Thurman:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blacker_the_Berry_(novel)

Last paragraph of the above:

The novel's line "the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice" has been used by several rappers, such as Tupac Shakur's 1993 song "Keep Ya Head Up,” Pharoahe Monch's 2007 song "Let's Go,” Dave's 2020 songs "Black" and "Run and Tell That" from the musical Hairspray, and more explicitly, Kendrick Lamar's 2015 song "The Blacker the Berry.”

Fauset: A significant writer whose work has fallen out of the public mind. Plum Bun is the novel most often mentioned, but she was also a poet, story writer and essayist. In 2017, The New Yorker ran a great piece on her, “The Forgotten Work of Jessie Redmon Fauset”:

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-forgotten-work-of-jessie-redmon-fauset

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jessie_R._FausetLarsen:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quicksand_(Larsen_novel)McKay:

Home to Harlem was the first best-seller by an African-American. First printed by Harper and Brothers in 1928, the novel quickly went to subsequent printings. It tells the story of Jack Brown, a black soldier who deserts the Great War in France and returns to Home to Harlem in the novel. The city’s nightlife is full of temptation for Brown, but the grit, grime and hardness of the industrial city are pitted against the idealism of rural life. Characters live within the frustration of intellectual potential and aspiration that is limited by prejudiced circumstances. Author Claude McKay was criticized for depicting stereotypes of lower-class blacks in the novel, while others celebrated what they considered realistic views of Harlem in the 1920s.

White: Flight is regarded as a “a groundbreaking novel of the Harlem Renaissance.”

Writing this note, I ran into a term new to me, “the literature of passing.” Nella Larsen’s novel, Passing (1929), has become well known in recent years, even before its film adaptation in 2021, but White’s novel pre-dates it by several years. I find that the University of Illinois Press has published, Passing and the Rise of the African American Novel by M. Giulia Fabi (2005); Weslyan University offered a class, Crossing the Color Line: Racial Passing in American Literature in 2010; a review of Brit Bennet’s second novel, The Vanishing Half, in The New Yorker is titled, “Brit Bennett Reimagines the Literature of Passing”; it comes up again and again in pieces on Philip Roth’s late novel, The Human Stain. Apparently, I’ve been living under a rock.

As it turns out, White was a very big deal. His lengthy bio in the New Georgia Encyclopedia begins: A native of Atlanta, Walter White served as chief secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1929 to 1955. During the twenty-five years preceding the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, White was one of the most prominent African American figures and spokespeople in the country.

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/walter-white-1893-1955/In 2022, NPR’s Fresh Air devoted a segment to White, headlined: “How one Civil Rights activist posed as a white man in order to investigate lynchings”—a conversation with the author of White Lies: The Double Life of Walter F. White And America's Darkest Secrets.

It’s absolutely worth a look:

https://www.npr.org/2022/03/30/1089640442/how-one-civil-rights-activist-posed-as-a-white-man-in-order-to-investigate-lynchWashington: An unattributed epistolary novel serialized in a Harlem magazine, The Messenger, as The Letters of Davy Carr: A True Story of Colored Vanity Fair. Not until 2003 was it published in book form after being unearthed by Adam McKible, a grad student researching his dissertation. McKible was able to trace its authorship to Edward Christopher Williams, Howard University’s head librarian during the 1920s.

Cane: Wiki’s entry on Cane begins:

The novel is structured as a series of vignettes revolving around the origins and experiences of African Americans in the United States. The vignettes alternate in structure between narrative prose, poetry, and play-like passages of dialogue. As a result, the novel has been classified as a composite novel or as a short story cycle. Though some characters and situations recur between vignettes, the vignettes are mostly freestanding, tied to the other vignettes thematically and contextually more than through specific plot details.

The novel's ambitious and unconventional structure, along with its lasting impact on subsequent generations of writers, has contributed to Cane's recognition as an important figure in modernism.

Cane has been more widely read since Toomer’s time. Its structure made it hard to pigeon-hole, and though Toomer is seen as a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance, he distanced himself from the movement. The book was praised, quibbled about, thought baffling by some critics, but it found more critical and popular traction in later years. Toomer is rather a complex figure, the arc of his life not quickly summarized. Here’s the Wiki link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Toomer

Have a great rest of your summer!

I am not white, and given the rarity of books from those of my background/geographic region, I usually read works by different authors. Unsurprisingly (and per usual), I have not read any of the books on this list. I accept your challenge though! I always enjoy diversifying my reading appetite!