[Note: Put cursor over footnote for pop-up.]

The Big Picture:

This was not a year teeming with great literary novels—or popular novels that made a big splash. A number of respected literary writers published novels in 1964, but by and large they weren’t the works we remember them for—Ralph Ellison, Iris Murdoch, Vladimir Nabokov, V. S. Naipaul, Mario Puzo, Gore Vidal, among others.

There were new mysteries/crime novels by Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Dick Francis, John D. MacDonald, Ross Macdonald, Ngaio Marsh1, Gladys Mitchell, Ellery Queen, Ruth Rendell, and Rex Stout, to name only a few.

Also new spy novels by Eric Ambler [A Kind of Anger], Ian Fleming [You Only Live Twice] and Len Deighton [Funeral in Berlin].

And a wave of new sci-fi by Brian Aldiss [Greybeard], J. G. Ballard2 [The Burning World ], William Burroughs [Nova Express], Philip K. Dick [Martian Time-Slip] and others.

The two books topping the New York Times bestseller list most of 1964 were published in 1963: Mary McCarthy’s, The Group, and John le Carré’s, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

The two 1964 works with the most staying power are children’s books:

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl

The Giving Tree, Shel Silverstein

The Well-Known/Popular Books:

Little Big Man, Thomas Berger3

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, Joanne Greenberg (under pen name Hannah Green6

Herzog, Saul Bellow7

Sometimes a Great Notion, Ken Kesey8

Last Exit to Brooklyn, Hubert Selby Jr.9

First novels by two major American writers:

Seven Memorable Works of World Literature:

Arrow of God, Chinua Achebe12 [Nigeria]

A Very Easy Death [memoir], Simone de Beauvoir 13 [France]

Beauty and Sadness, Yasunari Kawabata14 [Japan]

The Passion According to G.H., Clarice Lispector15 [Brazil]

Weep Not, Child, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (aka James Ngigi). 16 [Kenya]

When the Lion Feeds, Wilbur Smith [Rhodesia/South Africa]

A Personal Matter [memoir], Kenzaburo Oë [Japan] 17

Special Mention:

The Warren Report, The Warren Commission

Why We Can't Wait [essay/treatise] Martin Luther King Jr.18

Blues For Mister Charlie [play], James Baldwin19

The English translation of Labyrinths [stories], Jorge Luis Borges20

My List:

A Confederate General from Big Sur, Richard Brautigan 21

Because I Was Flesh [autobiography], Edward Dahlberg 22

Second Skin, John Hawkes23

A Moveable Feast [memoir], Ernest Hemingway 24

Postscript [i]:

I tried a new tactic for 1964’s books. In addition to Wikipedia [1964 in Literature], my reading, and other sources, I searched Abebooks.com for 1964 first editions and turned up several dozen books/writers absent on Wiki. Some were paperback originals—pulps such as The Revolt of Abbe Lee.

Others were hardcover novels from major presses that have vanished from the public mind. [Or at least I didn’t recognize the names or titles.]

But there were four I want to include here:

The Blind Heart, Storm Jameson25

Albert Angelo, B. S. Johnson26

The Dalkey Archive, Flann O'Brien 27

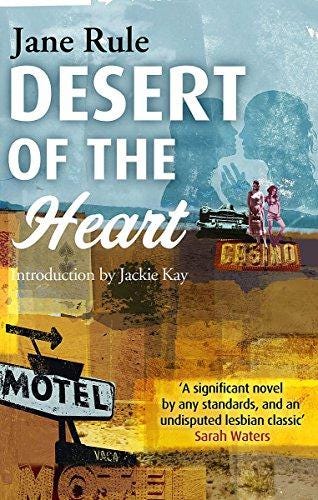

The Desert of the Heart, Jane Rule. 28

I hope they find a few new readers. You maybe?

Postscript [ii]:

Here are two neglected/forgotten book sites I found while working on today’s post:

https://www.boilerhouse.press

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-custodian-of-forgotten- books

Ngaio Marsh: Finally looked up this writer and discovered that she was a she, a New Zealander, a Dame Commander of the British Empire, and writer of 32 detective novels. Also learned that you say her first name Nigh-oh.

J. G. Ballard: An early example of a burgeoning sub-genre of dystopian fiction known as cli-fi. For an overview: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climate_fiction

Little Big Man: Not sure how popular this novel would be were not made into a popular film (an early Dustin Hoffman vehicle). I’ve never read it. Hoffman plays Jack Crabb, 121-year-old survivor of The Battle of Little Big Horn—we see him first (under a badlands worth of wrinkly make-up) being interviewed by a young historian; the rest of the film is all flashback, but Crabb’s ancient crackly voice keeps reminding us of the story’s frame. The Encyclopedia of the Great Plains says: “The portrayals of the Old West and Native Americans are exaggerated in every way. The film marks the beginning, however, of showing Native Americans as close to nature, spiritual, and victims of the white man.”

A memory: Old Lodge Skins tells Little Big Man that “it’s a good day to die,” and they proceed up to a rise where OLS lies down and awaits death. A very moving few moments. Then a few raindrops fall and OLS wakes and asks if he’s still in this world. “Yes, Grand-father,” LBM says. “Hunh,” OLS says, “sometimes the magic works and sometimes it doesn’t.” The rain starts pelting down harder. LBM gets OLS up and covers him and they make their way back to the camp.

William Golding: A major British writer, 1983 Nobel Laureate. Best-known for Lord of the Flies (1954), the first of his thirteen novels. The Spire, “an astonishing portrait of obsession, betrayal, and arrogance,” follows the construction (and near collapse) of an impossibly large spire on the top of a medieval cathedral (generally assumed to be Salisbury Cathedral). The Spire would also appear below on My List.

Little-known fact: Tom Chapin, a classmate of mine at Pomfret School, was the son of an artist and through that connection was chosen for the lead role [Jack] in the 1963 film Lord of the Flies. He became not an actor or artist but a geologist.

Bellow: Most readers consider The Adventures of Augie March (1953) their favorite Bellow novel, followed by Herzog [bestseller, winner of the National Book Award] and Humboldt’s Gift (1975) [Pulitzer Prize]. I don’t think Bellow had much interest in plots—they were basically a rack to hang his writing on; that said, he was a hell of a writer. He’s often said to be a novelist of ideas, yet I’ve always loved the great physicality of his writing. A few lines from Herzog:

The whole family took the street car to the Grand Trunk Station with a basket (frail, splintering wood) of pears, overripe, a bargain bought by Jonah Herzog at the Rachel Street Market, the fruit spotty, ready for wasps, just about to decay, but marvelously fragrant. And inside the train on the worn green bristle of the seats, Father Herzog sat peeling the fruit with his Russian pearl-handled knife. He peeled and twirled and cut with European efficiency. Meanwhile, the locomotive and the iron-studded cars began to move. . . . By the factory walls the grimy weeds grew. A smell of malt came from the breweries.

Herzog would also appear on my list.

Kesey: I’m not sure how Kesey is regarded these days. He was a serious writer who became a countercultural icon during the period just after the heyday of the Beats, remembered for having written One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), source of Miloš Forman’s film of the same name (1975), featuring Jack Nicholson’s bravura incarnation of Randle Patrick McMurphy, agent provocateur within a mental hospital . . . and for the odyssey across America with a group of loose cannons called the Merry Pranksters, which included Kerouac’s speed-fueled pal Neal Cassady driving the bus named Furthur:

[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Furthur_(bus)].

This period of Kesey’s life was famously documented by Tom Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), which is, itself, a wonderful introduction to “New Journalism”:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Electric_Kool-Aid_Acid_Test

Last Exit: From Wiki: “The novel takes a harsh, uncompromising look at lower class Brooklyn in the 1950s written in a brusque, everyman style of prose. Critics and fellow writers praised the book on its release. Due to its frank portrayals of taboo subjects, such as drug use, street violence, gang rape, homophobia, prostitution and domestic violence it was the subject of an obscenity trial in the United Kingdom and was banned in Italy.”

Joyce Carol Oates: An unstoppable force of nature (or graphomaniac). By my count, she’s published 124 novels, novellas, and story collections (including a bunch under her several pen names). Also taught, also edited The Ontario Review. All that said, she went out of her way to say something nice to me once, and she—along with Alice Munro, John Updike, and Cormac McCarthy—was a major influence on my story writing. The novella Black Water is an absolute killer. And the opening pages of Because It is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart are as fine a sample of beautiful, tough writing as you’re likely to find. I also love You Must Remember This (1987).

Anne Tyler: One of our most humane, dependable, life-affirming-without-being-saccharine novelists. In 59 years, she has written 24 novels (and a couple of children’s books). I’ve read too few of them—only eight. The Accidental Tourist (1985) is often cited as her best, along with Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant (1982), which was my first and still-favorite. Breathing Lessons (1989) was awarded the 1989 Pulitzer. I like her writing for many of the same reasons I like Ann Patchett’s [Commonwealth (2016) is my favorite of hers].

Achebe: His first novel, Things Fall Apart (1958), has long been the most-read, most-studied, most-translated African work. It was followed by No Longer at Ease (1960) and Arrow of God, the three forming “The African Trilogy.” Read about him:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinua_Achebe

de Beauvoir: Existentialist philosopher, political activist, feminist and social theorist, novelist, long-time paramour of Jean-Paul Sartre,. Best-known for her landmark book, The Second Sex (1949). A Very Easy Death is a day-by-day account of her mother’s death, also considered a major work.

Kawabata: A Nobel laureate in fiction (1968). Other significant works: Snow Country (1948), The Go Master (1951) A Thousand Cranes (1952).

Lispector: I have yet to read Lispector, though she’s a writer other writers recommend all the time. [There’s so much to read!]

Kudos pour in:

Rachel Kushner: “Lispector's most unrelenting and serious work. The new rendition, by Idra Novey, should be regarded as an event.”

Boston Globe: "Lispector's prose is unforgettable... still startling by the end because of Lispector's unsettling forcefulness."

The Rumpus: “A lyrical, stream of consciousness meditation on the nature of time, the unreliability of language, the divinity of God, and the threat of hell."

TLS: "Her images dazzle even when her meaning is most obscure, and when she is writing of what she despises she is lucidity itself."

Ngũgĩ: Long considered the leading figure in East African writing. Weep Not, Child was his debut novel. Also known for A Grain of Wheat (1967) and Wizard of the Crow (2004), which is in my TBR stack (the multi-colored spine is staring at me from across the room).

He has complex history; read about him here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9_wa_Thiong%27o

Ōe: The 1994 Nobel Laureate in Literature. This semi-autobiographical novel addresses the presence of his brain-injured son Hikari in his life.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Personal_Matter

Despite Hikari’s severe limitations, he composes music—read about it here:

https://www.publishersweekly.com/9780684824093

MLK: An essay/treatise on the power of nonviolent resistance, includes the seminal text, ”Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Often cited as bringing the civil rights movement to a wider national audience.

Baldwin: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blues_for_Mister_Charlie

Borges: A major figure in Latin American literature, an inspiration to what’s known as the Latin American Boom, which produced the likes of Garcia Marquez, Vargas Llosa, Paz, Cortazar, Fuentes and others. It’s hard to overestimate the impact of these newly translated stories on North American writers. His stories work with philosophical riddles, questions about chance and doubles, dream landscapes, strange histories, etc. He’s considered a precursor to the school of magic realism. Labyrinths is a must-read.

Here’s a piece of the note I wrote about him for his early collection, The Garden of Forking Paths, in the post Reading Projects [1] The 1930s:

One snowy night in the early 1970s I sat in the back of a lecture hall in Kalamazoo, Michigan, as, way down in front the blind, elderly Borges stood beside his handler and took questions shouted down from the peanut gallery. If anyone led with, Señor . . . he’d go, No, just Borges! I still can’t believe I was there.

Brautigan: Evaluating Brautigan from this late date is tricky. He was a serious poet and prose writer with an unharnessed imagination and a taste for whimsy, but he became a darling of the counterculture, which has skewed our understanding of his work. Trout Fishing in America (1967) I still think is a great book, but (though I haven’t been back to them in a long time) I remembering finding his later stuff less wonderful. I also believe his wide readership failed to appreciate his unhappiness/depression/substance abuse, wanting to see him as the hippie icon pictured here:

Dahlberg: Novelist, essayist, critic, teacher. I’d never heard of him when I happened onto his memoir, but was enthralled by his life and his fearless writing, his willingness, at times, to say the kind of squirmy thing most of stop short of saying. Minor example: How good and right our conduct is when our testicles are empty.

I had lots of other lines underlined, but I must’ve lent the book to someone . . .

Hawkes: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hawkes_(novelist)

Hawkes is a hard novelist to characterize, and a hard writer to feel close to. His books are sometimes termed post-modern, which may or may not help. He was a great teacher [Brown University] and craftsman but there’s a degree of oddness/perversity that make the work more fascinating than “fun to read.” Also known for: The Cannibal (1949), The Lime Twig (1961) The Blood Oranges (1970), Whistlejacket (1988) and others. My pick is the unquestionably perverse short novel, Travesty (1976)—see Reading Projects [7]: Oddball Novels.

Hemingway: A group portrait of the American ex-pat writers in Paris in the 1920s. I haven’t read this in years, yet it was involved, somehow, in my becoming a writer. You should read two other books along with this one, Malcolm Cowley’s, Exile’s Return (1934, revised 1951), and Sylvia Beach’s, Shakespeare and Company (1959). Besides running the bookstore of that name, a major hangout for the ex-pats, she also published the first edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922).

B. S. Johnson: See the footnote for his other major work, The Unfortunates; Birth Year Project: 1969.

Flann O’Brien: At least two previous posts have mentioned O’Brien’s best-known book, At Swim-Two-Birds (1939). You can read about O’Brien here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flann_O%27Brien

I haven’t read The Dalkey Archive, but it’s the namesake of an indie press dedicated largely to rescuing neglected/forgotten books:

https://www.dalkeyarchive.com/

Jane Rule: From Wiki: . . . a Canadian-American writer of lesbian-themed works. Her first novel, Desert of the Heart, appeared in 1964, when gay activity was still a criminal offence. It turned Rule into a reluctant media celebrity, and brought her massive correspondence from women who had never dared explore lesbianism. Rule became an active anti-censorship campaigner, and served on the executive of the Writers' Union of Canada.

See also: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jane-vance-rule

Thank you! This is a great list. I'm definitely mining this for my husband's birthday.