[Note: Put cursor over footnote for pop-up.]

Even if you absolutely love realism,1 you need a vacation from it now and then. You need to go somewhere else. Even the most committed to what is crave the taste of what could be. And what amazes me is how readily, how trustingly or unwarily I accept a story’s premise.

Let’s say it begins:

That morning I was on a bench overlooking the bay when a crow flapped down and took the spot beside me. “David,” the crow said, “lemme give you a word of advice. That OK?”

The reader in me goes, “So what’d he tell you??”

If you’re a writer, especially. It’s good to be reminded how capacious the house of fiction is. It’s good to be shaken up by writers who are less fettered to the ordinary than you are. But what does that mean, “fettered to the ordinary”? Resistant to writing differently? But what does “differently” mean?2 It might mean not ruling out story stuff that you habitually rule out. It might mean letting yourself choose a story element/story format/story persona that lives not at the top of your bell curve but way off to one side, where the odds become really really small?3

Today’s list is a shotgun blast of oddball-ness.

Today’s list is a shotgun blast of oddball-ness. Odd things happening within stories. Odd people telling stories. Writers telling stories oddly. Writers re-purposing existing forms.4 Stories you think are one kind of artifact but are actually another. Stories where everything’s just like our world, except for this one thing. Stories that expand or constrict the flow of time. Stories where the parts are quirkily assembled, or seem unconnected from each other, or where you wonder, What makes this a novel??5

If you like “weird” literature, there’s plenty out there—and a few in this post qualify. But mostly I’ve avoided out-and-out horror, and stuck to literary writing. You’ll recognize some of the titles from earlier posts.

As usual, the list starts with my own reading [*] and is augmented by poking about online.

The List:

Long Way Down [YA graphic novel], Jason Reynolds and Danica Novgorodoff (2022)6

And I Do Not Forgive You: Stories and Other Revenges, Amber Sparks (2020)

*Shadowbahn, Steve Erickson (2017)7

S., J. J Abrams and Doug Dorst (2013)

The Vanishers, Heidi Julavits (2013)

*Familiar, J. Robert Lennon (2012)

Fat Girl, Terrestrial, Kellie Wells (2012)

The Islanders, Christopher Priest (2011)8

Zazen, Vanessa Veselka (2011)9

The Interrogative Mood, Padgett Powell (2009)10

Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry

[graphic novel] Leanne Shapton (2009)

*The Gone-Away World, Nick Harkaway (2008)

*The Raw Shark Texts, Steven Hall (2007)

Un Lun Dun, China Miéville (2007)11

*Explorers of the New Century, Magnus Mills (2005)12

*I, the Divine: A Novel in First Chapters, Rabih Alameddine (2001)

*This Is Not a Novel, David Markson (2001)13

*House of Leaves, Mark Danielewski, 2000

Lives of Monster Dogs, Kirsten Bakis (1997)

*The Unconsoled, Kazuo Ishiguro (1995)

*The Rings of Saturn, W. G. Sebald (1995)

*Jesus’ Son [linked stories], Denis Johnson (1992)

*Written on the Body, Jeanette Winterson (1992)14

*Time’s Arrow, Martin Amis (1991)

*The Mezzanine, Nicholson Baker (1988)15

*Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, Haruki Murakami

(1987)

Sphinx, Anne Garréta (1986)

*Riddley Walker, Russell Hoban (1980)16

*If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler, Italo Calvino (1979)

*Speedboat, Renata Adler (1976)17

*Travesty, John Hawkes (1976)18

*J R, William Gaddis (1975)

*The Fan Man, William Kotzwinkle (1974)19

*Red Shift, Alan Garner (1973)

*Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino (1972)20

The Unfortunates, B. S. Johnson (1969)

*The Universal Baseball Association, J. Henry Waugh, Prop., Robert Coover

(1968)21

*Trout Fishing in America, Richard Brautigan (1967)22

Three Trapped Tigers, Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1967)23

*Ice, Anna Kavan (1967)

*Hopscotch, Julio Cortazar (1966)

*Aura [novella], Carlos Fuentes (1962)24

*Naked Lunch, William Burroughs (1959)

Jealousy, Alain Robbe-Grillet (1957)25

*Pedro Páramo, Juan Rulfo (1955)26

*Molloy, Samuel Beckett (1951)27

Exercises in Style, Raymond Queneau (1947)

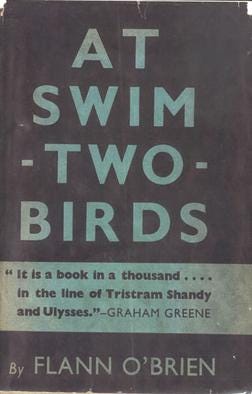

*At Swim-Two-Birds, Flann O’Brien (1939)28

*Sheppard Lee: Written by Himself, Robert Bird Montgomery (1836)29

The Project/Challenge:

Excluding any you’ve already read, find (at least) one book from each decade group that speaks to you. Read it/them. Seven books in all. No deadline. Sounds pretty do-able to me. You have permission to pushpin a piece of yellow tablet to the wall of your office/study/workroom/hideyhole; whenever you finish a book, between now and the Twelfth of Whenever, enter the title and author and year published. C’est tout. You could even have several challenges going simultaneously. If you’d like, substitute oddball reads of your own discovery for one or two of mine.

And finally, a list from Book Riot:

https://bookriot.com/i-got-your-weird-right-here-100-wonderful-strange-and- unusual-novels/

Realism: And I absolutely do. I love the mundane [mundus, Latin, the world]. I love books like TaraShea Nesbit’s The Wives of Los Alamos (2014), Kent Haruf’s Plainsong (1999), William Maxwells’s So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980), Leonard Gardner’s Fat City (1969), George Orwell’s, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), et al.

Differently: It might mean a different practice—time of day, not revising until later, writing as fast as you can, writing at the coffee shop, writing with/without coffee . . . or whatever, but that’s a topic for a different day.

Bell curve: Small, but as any student of physics would tell you, non-zero. And that’s where things get juicy. As the likelihood of a thing occurring plummets, the potential for readerly wonder skyrockets.

Borrowed forms: I once read a flash fiction written in the form of a book’s acknowledg-ments page—as it proceeds, you see what a freeloading pain in the ass the guy must’ve been.

Leanne Shapton’s novel [Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry, see today’s list] consists of an auction-house catalog—photos, item descriptions . . . the memorabilia of a failed relationship. The power of stuff.

[I remember staring at my father’s suits hanging in the closet after he died, and thinking, before the other side of my brain stepped in, Why are the clothes here but not the man??]

Is it a Novel? An issue in some of David Mitchell’s books, along with David Markson’s in today’s post, as well as Denis Johnson’s, Jesus’ Son, sold as a collection of stories, yet, to my mind a novel. In general, though, my rule tends to be: If the writer says it’s a novel, it’s a novel.

Long Way Down: The novel covers sixty seconds of time.

Shadowbahn: This novel appeared in the post, Reading Project [4]: Speculative Fiction, along with The Raw Shark Texts, House of Leaves, The Unconsoled, Time’s Arrow, Ice, and Sheppard Lee: Written by Himself. I haven’t re-footnoted these titles, but you can hit the link and chase them down if you’d like.

The Islanders: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Islanders_(Priest_novel)

From the above: The Islanders is written as a guidebook to a series of fictional islands, using the literary device of an unreliable narrator. As it portrays and describes a number of the exotic islands, the specific details shift as the story is told, including the names and locations. There are islands that have been sculpted into vast musical instruments, others are home to lethal creatures, others the playground for high society.

Zazen: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/678115/zazen-by-vanessa-veselka/

The Interrogative Mood: What do you think this one consists of?

Un Lun Dun: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Un_Lun_Dun

Explorers of the New Century: In Reading Projects [2]: Guilty Pleasures, I included Mills’ Restraint of Beasts with this footnote:

My first Magnus Mills. Black humor drollery. I didn't bond with some of his later books . . . but then there was Explorers of the New Century (2005). The blurb starts out: “It is the beginning of the century, and two teams of explorers are racing across a cold, windswept, deserted land to reach the furthest point from civilisation.”

The writing has the flavor of a boy's adventure book of yore. But, you see, actually . . . nope, not going to spoil it for you.

David Markson: Toward the end of his writing life, Markson wrote four books known as The Notecard Quartet. They consist of snippets of fact and commentary about writers, writers’ deaths, about the project you’re reading, and so on—terse fragments, many to a page. This Is Not a Novel was the first I read and remains my fave—though you could read all four together as a single work. The others: Reader’s Block (1996 ), Vanishing Point (2004), and The Last Novel (2007). These may be an acquired taste, but I love them. I love the way ideas/facts/statements rise and fall and how despite being told that it’s not a novel [this is just a feint, really, homage to Magritte’s painting of a pipe that isn’t a pipe, and, before that, Diderot’s story “Ceci n’est pas un conte”] it succeeds in being a novel, IMHO. Embedded, like an armature, is the Latin phrase, Timor mortis conturbat me, a refrain from medieval poetry, The fear of death disturbs me.

Written on the Body: Winterson has poured out a steady stream of slender, sui generis works since Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit appeared in 1985. Written on the Body is the story of a love affair between the narrator and a married woman; what distinguishes it is that the narrator’s name and gender are withheld, making us absorb the story in a kind of quantum physical way, several realities/possibilities superimposed on it, Schrodinger’s-cat fashion.

The Mezzanine: The time span of a man’s lunch hour.

Riddley Walker: Turtle Diary (1975) was my first Hoban book. A quiet thoughtful read, later made into a film of the same title with Glenda Jackson and Ben Kingsley. Nothing prepared me for the creative leap/world-building of Riddley Walker. Here’s the opening:

On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld boar he parbly ben the last wyld pig on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint looking to see none agen.

And one more surprise: This is the same Russell Hoban who wrote the Frances the Badger books and dozens of other books for kids. Go figure.

Speedboat: https://www.nyrb.com/products/speedboat

Travesty: Wiki calls Hawkes “a postmodern American novelist, known for the intensity of his work, which suspended some traditional constraints of narrative fiction.” That sounds about right. His books are short, strange, rather perverse, a category of one. The Lime Twig. Second Skin. Death, Sleep and the Traveler. Blood Oranges. Whistlejacket.

Travesty is a monolog delivered by the driver of car hurtling at night through the French countryside. He’s addressing his two passengers—his friend, and his (the driver’s) daughter, lover of the friend—explaining that soon, inexorably, he’ll drive the car into a stone wall. Did I say perverse? How can we stand to read such a thing? Really, that’s an excellent question; it’s the same one we ask of The Virgin Suicides [Jeffrey Eugenides, 1993]: How can we bear the story of the five Lisbon sisters killing themselves? And the answer is the same: Because of the voice. Eugenides adopts the collective sound of the neighborhood boys who loved these girls. [If it’s the case that first-person stories are always about the narrator, it’s true as well for the rare instances of first-person plural narration.]

Anyway, here’s how Hawkes’ narrator sounds:

No, no Henri. Hands off the wheel. Please. It is too late. After all, at one hundred and forty-nine kilometers per hour on a country road in the darkest quarter of the night, surely it is obvious that your slightest effort to wrench away the wheel will pitch us into the toneless world of highway tragedy even more quickly than I have planned. And you will not believe it, but we are still accelerating. As for you Chantal, you must beware. You must obey your Papa. You must sit back in your seat and fasten your belt and stop crying. And Chantal, no more beating the driver about the shoulders or shaking his arm. Emulate Henri, my poor Chantal, and control yourself.

The Fan Man: Horse Badorties, man.

Invisible Cities: The Travels of Marco Polo re-imagined.

The Universal Baseball Association, J. Henry Waugh, Prop.: It starts to dawn on you after a few pages that this baseball game you’re following isn’t what you thought it was. At some point you might notice how close J. Henry Waugh and is to Yahweh/YHWH.

Trout Fishing in America: How I loved this book when I was in my 20s. I’m almost scared to look at it now.

Three Trapped Tigers: Cabrera Infante’s first novel. Considered a classic of the Latin American Boom. The original title: Tres Tristes Tigres is a Spanish-language tongue twister. He spent much of his life in exile from his native Cuba.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tres_tristes_tigres_(novel)

Aura: My first exposure to second-person narration:

For a long time, I couldn’t find a copy in English and tried picking my way through a Spanish-language copy, to little avail. And then it was available again. A strange novella, close to my heart for personal reasons.

My wife loves The Old Gringo (1985). The two of us met Fuentes in 2012 when he came to the University of Puget Sound to read; afterward, he signed books and we talked with him a moment, expressing our long-time admiration and so on. I was driving across Tacoma a couple of weeks later and the news reported his sudden death.

Robbe-Grillet: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Jalousie

Pedro Páramo: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_P%C3%A1ramo

From the above: Gabriel García Márquez has said that he felt blocked as a novelist after writing his first four books and that it was only his life-changing discovery of Pedro Páramo in 1961 that opened his way to the composition of his masterpiece, One Hundred Years of Solitude. More-over, García Márquez claimed that he "could recite the whole book, forwards and backwards." Jorge Luis Borges considered Pedro Páramo to be one of the greatest texts written in any language.

Molloy. The first of Beckett’s trilogy, followed by Malone Dies, and The Unnamable]. Beckett was an Irish ex-pat, living most of his life in Paris; he wrote these novels first in French. I remember wading into Molloy a bit gingerly, expecting pure existential despair, ala Sartre.

Page 1: The narrator is at his mother’s, confused. How did he get here? He’s not sure about that. Then there’s this:

The truth is I don’t know much. For example, my mother’s death. Was she already dead when I came? Or did she die later? I mean enough to bury.

Enough to bury? I’m sorry, this put me in hysterics. I had him all wrong. Forget French. This was the black, self-lacerating humor of Irish pub stories, of wakes. If you don’t hear the undercurrent of fierce comedy in Beckett, he makes no sense at all.

A few pages later: :

Yes, the confusion of my ideas on the subject of death was such that I sometimes wondered, believe me or not, if it wasn’t a state of being even worse than life.

At Swim-Two-Birds: Wiki says: “ . . . a 1939 novel by Irish writer Brian O'Nolan, writing under the pseudonym Flann O'Brien. It is widely considered to be O'Brien's masterpiece, and one of the most sophisticated examples of metafiction.” A cult classic. Last summer, one of our subscribers wrote to say he was going to add the opening line of At Swim-Two-Birds to his personal HoF:

Having placed in my mouth sufficient bread for three minutes' chewing, I withdrew my powers of sensual perception and retired into the privacy of my mind, my eyes and face assuming a vacant and preoccupied expression.

Sheppard Lee: https://www.nyrb.com/products/sheppard-lee-written-by-himself