[Hover cursor over footnote for pop-up]

1.

A post I saw the other day: The only sin is boring the reader.

So let that be the text for today’s . . . almost said sermon, but that put me in mind of itchy legs on a hardwood pew. Let’s go with chat. Anyway, you know those photos that show someone’s bone-headed fail, and the caption says: You had one job!

A writer’s one job is to keep the reader reading. We stop reading when we stop being engaged,1 when we believe our time’s being squandered, when our sense of expectation withers. So what sort of writing does keep us engaged?

Let’s look at that word, expectation. It’s crucial because it means that writing—unlike painting and sculpture and still photography—is an art form you don’t take in all at once. Instead, writing unfolds, it reveals its shiny beads one at a time. This unfolding creates anticipation: What’s coming next?? But if what comes next is only what a reader expects, already knows, then the gears start to disengage. On the other hand, the undermining of expectations keeps us sharp, alert.

We also put the book down when it feels like nobody’s up in the control booth. What a huge difference there is between readers not knowing where a passage is leading (i.e., being kept in suspense) and the writer not knowing—or kind of knowing, or not having the patience or smarts to get there.2

I used to tell students: Good stories lean forward.

What did I mean? That good stories are infused with the particular quality of feeling purposeful. They have arcs, they’re aimed. And this quality is present throughout the artifact. The story as a whole has it, but also its smaller structures—the subsections, even the paragraphs, even the sentences.

Another thing I told students: A paragraph is not a paper bag to throw things into.

What I meant by that, of course, is that paragraphs are designed. They work, most of the time, exactly the way we were taught in school: topic sentence, development/examples, concluding statement or transition to next topic sentence.

In other words, Beginning, middle, end.

Topic sentences in fiction are steeped in voice/personality/story stuff, but they’re still topic sentences. I crack open Bonnie Jo Campbell’s terrific new novel, The Waters (2024) to a random page (the start of Chapter Nine, as it turns out). Here’s the first sentence:

When word got around that Rose Thorn was back, men and women who lived in Whiteheart and were one or two or three generations removed from their family farms felt a curious buzzing in their feet and legs, as well as farther up than they wanted to discuss.

The topic: the effect of Rose Thorn’s return to Whiteheart has on its citizenry. The body of the paragraph illuminates/unfolds that topic—lets us see some of it—and the final sentences sets up the next topic sentence.

Beginning, middle, end.

2.

Let’s say you’re a writer. And let’s say some trouble-maker comes along and puts their thumb over the last part of a sentence you’ve just written.

Question: How often could someone else figure out the covered part?

In dull writing, the answer is “pretty damn often.” In writing that keeps us alert and engaged, it’s “once in a while, maybe.” [Wait, why not all the time? Because: a) then the mandate to surprise would seem desperate/gimmicky, not the product of an agile mind; b) sometimes we need simple worker sentences; and c) the fear of repeating words can cause “symptom-itis”—as when the reporter covering the year’s first snow on local TV calls it “the fluffy white stuff.”]

OK, an example. In his story, “The Body in Extremis”3 Steve Almond writes:

If absence makes the heart grow fonder, ultimatum [ ]. The set-up suggests this vs. that, so we already hear:

. . . makes the heart grow [ ]. But we’d never guess the final word, feral. It’s a feral word. Only Almond would pair it with heart.

If absence makes the heart grow fonder, ultimatum makes the heart grow feral.

So what’s the take-away?

Unexpected (even shocking) word

. . . held back until the last beat of the sentence (like a punch line)

. . . repeats f sound (playing up the comparison/contrast)

. . . creating a statement we’ve never heard before

. . . which has a mysterious emotional resonance.

3.

The rest of today’s post will be . . . I was going to say “a shitstorm of examples.” What do you think? Too crude? How about: “The remainder of today’s post consists of many examples of sentences in which authors display their comprehension of the important principle of providing the reader with the occasional unexpected locution.” Yuh, I agree, too many words—not to mention way too Latinate. OK, let’s see. . . actually, I don’t have a shitstorm of examples, just a modest little pile, so maybe “shitflurry”? Or maybe— What’s that? This joke’s gone on too long? Right. I take your point.

Some examples:

Polish writer Bruno Schulz4 describing flocks of crows bursting from churchyard trees at dawn “like gusts of soot.”

—“Birds” in The Street of Crocodiles (aka Cinnamon Shops (1934)

And Aleksander Tišma depicting a night’s desolation:

Or the wind blows, biting and dry . . . sweeping dead debris . . . from cracked earth and faded asphalt into windows, under doormats and doors, down noses and throats, making people cough and choke, tearing posters from poles, bending trees in parks and rattling the craftsmen’s tin signs till they squawk like frightened poultry. —The Book of Blam (1972)

The model in both is X is like Y: flying crows/gust of soot . . . tin sign in wind/sound of frightened chickens. In both, the surprise comes with the second half of the comparison, reserved for the end of the sentence—both are precise and evocative without being truly shocking.

But sometimes a different model is used: X and Y aren’t themselves alike, but Y makes you feel the way X makes you feel. Here’s Saul Bellow:

. . . a few days before I had been in Sicily where it was warm. Here it was freezing when I arrived; when I came out of the station the mountain stars were barking.

—The Adventures of Augie March (1953)

Barking stars!

Or the opening of Andrea Lee’s short story, “Winter Barley”:

Night; a house in northern Scotland. When October gales blow off the Atlantic, one thinks of sodden sheep huddled downwind and of oil cowboys on bucking North Sea rigs. Even a large, solid house like this one feels temporary tonight like a hand cupped around a match.

—in Interesting Women: Stories (2002)

Or another from Schulz:

About that time we noticed that Father began to shrink from day to day, like a nut drying inside the shell. —“Visitation” in The Street of Crocodiles (1934)

(This one is also an example of what I talked about last week in "Hacksaw, Pesto, Tuning Fork": physicalizing the non-physical.)

And one more I love, from Jane Hirshfield’s essay, “Poetry and the Mind of Concentration”:

Difficulty . . . is not a hindrance to an artist. Sartre called genius “not a gift, but a way a person invents in desperate circumstances.” Just as geological pressure transforms ocean sediment to limestone, the pressure of an artist’s concentration goes into the making of any fully realized work.

—in Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry (1997)

4.

Underwear isn’t funny, someone once said, but underwear on your head is.

Incongruity, in other words. A thing in the wrong place. The word feral in Almond’s sentence.

In Joyce Carol Oates’, Black Water (1992), her reworking of the events at Chappaquiddick, after the unnamed Senator loses control of his car, the Mary Jo Kopechne character

. . . heard, as the Toyota smashed into a guardrail that, rusted to lacework, appeared to give way without retarding the car’s speed at all, The Senator’s single startled expletive—“Hey!”

It’s lacework, the very opposite of what we’d hope for in a guardrail. But haven’t we seen iron rusted to a crumbly filigree? And doesn’t this word, in its femininity, echo the violation of trust occurring in the larger story?5

The hallucinogenic character known as The Kid in Cormac McCarthy’s final novel, The Passenger (2022) is said to have been brought into the world with icetongs. A terrifically disturbing choice of word.6

In Nobel Laureate, Ivo Andrić’s historical novel, The Bridge on the Drina (1945), I ran into a wonderful (?) display of appalling meets the benign—we’re shaken by this incongruity, our complacency is broken down:

On sunny days [the executioner] would sit or lie all day long on the bridge in the shade under the wooden blockhouse. From time to time he would rise to inspect the heads on the stakes, like a market-gardener his melons.

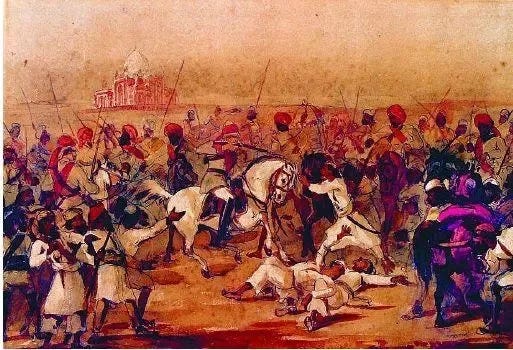

J. G. Farrell uses the same strategy in The Seige of Krishnapur (1973),7 his fictional account of 1857’s Sepoy Rebellion:

. . . the smell from the decaying offal and from the corpses of men and animals became intolerable and hung constantly, undisturbed by wind, as a foul miasma over the fortifications. While the lull in the firing persisted, the Magistrate ordered earth to be thrown over the rotting mountain of offal in order to cover it like the crust of a pie.

OK, that was grim. In recompense, I saved you the best one. John Dos Passos is mostly known today for his three-volume work, The U.S.A. Trilogy [The 42nd Parallel (1930), 1919 (1932), The Big Money (1936)]8. I haven’t read it, but I have read (and loved) Manhattan Transfer [1925].9

Note, below, how a writer can sandbag you with a run of plain sentences, then, when you drop your defenses for a second, nail you with a zinger:

She stood in the middle of the street waiting for the uptown car. An occasional taxi whizzed by her. From the river on the warm wind came the long moan of a steamboat whistle. In the pit inside her thousands of gnomes were building tall brittle glittering towers.

Engaged: Up to about twenty years ago, my cars had stick shifts, so this word, engage, calls up the engaging of gears—meshing, syncing, grabbing. It was visceral—you felt it in your left foot and right hand. Carry that meaning into your writing.

Ignorance: Every story begins with not-knowing. Maybe you free write, or write in a journal—whatever jumpstarts you. But I’m talking about completed, revised, edited work. By then you must know your story—the whole of it, but also its parts—how they function, why they’re there. Is some of it there because you did the research and want it to show? Is some of it just really cool and you can’t bear to take it out? Is it there because you didn’t see how much sleeker a passage would be without it?

In My Life in Heavy Metal (2002). I met Steve many years ago when I did a workshop at Univ. of North Carolina Greensboro; he was a young grad student with a palpable hunger to make it to the big leagues. I’m happy to report that he did—he’s got a slew of books, fiction and nonfiction, including Candyfreak: A Journey Through the Chocolate Underbelly of America (2004) and a forthcoming book on writing, Truth Is the Arrow, Mercy Is the Bow: A DIY Manual for the Construction of Stories (April 2024).

[Also happy to report that one of Steve’s classmates was poet Camille Dungy, whose nonfiction work, Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's Garden (2023) has made a splash. (Maybe “splash” isn’t that good for a book about dirt.) Anyway, a book that’s gotten well-deserved attention.]

Schulz: From Wiki: “Schulz was shot and killed by a Gestapo officer in 1942 while walking home . . . with a loaf of bread.” Read the rest:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruno_Schulz

Oates: Moments later, The Senator will kick the young staffer in the head as he wriggles free and swims, alone, to safety.

Icetongs: Of course, McCarthy was a master of disturbing words, sometimes of his own coinage.

Seige of Krishnapur: A Booker winner, part of Farrell’s Empire Trilogy (with Troubles (1970) and The Singapore Grip (1978).

Dos Passos: Read about that here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S.A._(trilogy)

Also Dos Passos: I posted these a few weeks ago, Voice [3], I think. All through Manhattan Transfer you find great passages, great sentences—sometimes conventional ones that are just beautifully made, such as:

A car whirred across the bridge making the girders rattle and the spiderwork of cables thrum like a shaken banjo.

Others, like the one I talk about in the post, come out of nowhere and bowl you over.

And he had a great for New York City patois—here’s another I love:

“Say Anna,” says a broadhipped blond girl . . . “did ye see that sap was dancin wid me? . . . He says to me the sap he says See you later an I says to him the sap I says see yez in hell foist . . . an then he says, Goily he says . . . "

You "almost said sermon"....So, since you introduced that term into your piece, here's a random thought from a reader about 'sermonizing', a term which as used these days strayed from its original meaning of 'writing or delivering a sermon or homily in a religious setting' (as defined by Poor Richard's New American Almanack, post-modern edition) (yes, it's made up by "Poor Richard"). 'Sermonizing' is a term used nowadays -- "in the parlance of our times", to crib from the Cohen brothers -- to describe ironically a statement presented as fact or as an argument for the factual basis of a belief or opinion. Sermonizing is a variant of 'lecturing', however it connotes an element of uncertainty as to the statement's accuracy, whether willful or inadvertent. Often decoratively wrapped in layers of latinate arcana, parenthetical elucidations and delivered with a plonking, self-assured tone of one possessed of superior wisdom, such sermons are often delivered no so much as contributions to the discourse but as a means to end it, on terms most favorable to the sermonizer's self-regard.

"Thus endeth the lesson for today". (q.e.d.).