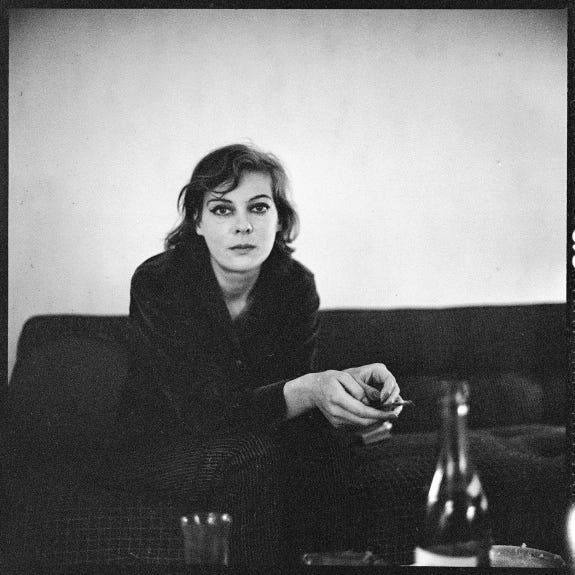

Lady Caroline Blackwood [photo by Walker Evans]

Starting a new series today: Sixes, a smallish stack of books (mostly fiction) that go together—thematically, geographically, structurally, historically, aesthetically, or for some other reason that seems worth noticing. These will appear now and then.

First, some thoughts . . .

Digital publishing has been a godsend for readers of books off copyright. If you want the naked text (that is, minus modern introduction, such as Penguin or Oxford University Press provide, etc.) and don’t mind reading on a Kindle1 or the like. Most can be had for free. I downloaded Anthony Trollope’s forty-seven novels (gratis) in about ten seconds.

The landscape is quite different for writers still under copyright—early and mid-20th century writers, say.

Four of today’s books are reprints from New York Review of Books Press.2 Like Persephone Books (and others such as Virago Books), NYRB is a major rescuer of literary fiction. Thanks be to them, and thanks be to book nerds like us who read and talk up these works.

SIX KEENLY WRITTEN NOVELS BY WOMEN YOU PROBABLY HAVEN’T READ (1954-1983):

In the Reign of the Queen of Persia, Joan Chase (1983)3

Good Behaviour, Molly Keane (1981)4

Norma Jean, The Termite Queen, Sheila Ballantyne (1975)7

Cassandra at the Wedding, Dorothy Baker (1962)8

The Moonflower Vine, Jetta Carleton (1962)9

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, Barbara Comyns (1954)10

Barbara Comyns and daughter Caroline in 1938

Or maybe you have read some of these . . . or will. Maybe you’ll think, You know, Long’s a not-half-bad book recommender . . . I oughta try one of these.

And you do!

Then, maybe, you’ll say to yourself, Well, that was actually a good read—a little dark in spots—but aren’t we all? I wonder what it’s got to do this other one on the list? And before you know it, you’ve read another one, then, lo, a third!

Stranger things have happened, mes amis.

You might expect a person who doesn’t have a smart phone (me) would take an equally Luddite-ish view of e-readers. Au contraire. I love paper books, viscerally, aesthetically. But I also love my Kindle (a Paperwhite)—its capaciousness, its portability, its ease of use, the fact that I can look up a book in the Seattle Public Library catalog, see that it’s available, and be reading it (under the bedcovers, often) in no time.

Also, as an old guy, one of my tasks is to “get rid of stuff.” When I was teaching I’d bring a big Rubbermaid tubful of books to residencies and they’d disappear. A couple of times I put out the word on Facebook: You send me media mail postage and I send you five books—that took care of a couple of hundred, but the packaging up was a pain. One of these days, I’m going to stock up the Ford and crisscross Tacoma’s North End, feeding the little free libraries. But I digress. How you do your reading is up to you.

NYRB: They often resuscitate one or more of a writer’s other books, since it’s frequently the case that even prolific writers of earlier eras are remembered for a single work. They also aggregate pieces scattered throughout a writer’s publishing life. For example, NYRB has reprinted Elizabeth Hardwick’s most iconic book, Sleepless Nights (1979), but have also issued The Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick (2017) and The New York Stories of Elizabeth Hardwick (2010).

You can see novelist Lauren Groff’s appreciation of Sleepless Nights here:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/26/books/elizabeth-hardwick-sleepless-nights.html

[Hardwick will re-appear in today’s post, below.]

Joan Chase: I’m including an obit for her, which gives a brief overview of her writing life and sense of privacy. The NYRB blurb compares this novel to the stories of Alice Munro and Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping. I agree.

[Just now, typing this note, I remembered another novel that belonged in today’s post! So I’ve gone and added it, which means, of course, that this inaugural post of Sixes has a plus-one. Call it a lagniappe.]

Anyway, two links for Chase:

https://www.nyrb.com/collections/joan-chase

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/03/obituaries/joan-chase-who-drew-acclaim-with-first-novel-at-46-dies-at-81.htmlMolly Keane: I just read this one and it’s pretty delicious. The title is like a faceted stone—depends on which direction the light’s coming from. Note: Don’t let the fact that the narrator may have murdered her mother in the opening pages stand in your way, OK?

Keane was Irish. Her real name was Mary Nesta Skrine, but published her novels and plays under the name M. J. Farrell. She married Bobby Keane in 1938, and they had two daughters. Then, in 1946, the husband died suddenly, her most recent play flopped, and she published nothing for the next twenty years. Only then came Good Behaviour, the first work to appear under her own name.

https://www.nyrb.com/products/good-behaviour

Caroline Blackwood: Saw this novel recommended, read it, loved it. Only later did I learn who Blackwood was: Guinness heiress, famous socialite, wife of painter Lucian Freud, wife of pianist/composer Israel Citkowitz, wife of poet Robert Lowell.

I was so intrigued by all this, and the images of her—photographs by the likes of Walker Evans, paintings and drawings by others including Freud—that I read Nancy Schoenberg’s riveting biography of her, Dangerous Muse (2001).

https://bookshop.org/p/books/dangerous-muse-the-life-of-lady-caroline-blackwood-nancy-schoenberger/16436422?ean=9780306811876

A few other links:

https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/features/why-you-should-read-great-granny-webster-by-caroline-blackwood

https://thedecadentreview.com/corpus/caroline-of-clandeboye/

But I promised you more about Elizabeth Hardwick. Here’s the opening of the New York Times review of The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979:

. . .brings to life one of literary history’s most famous scandals. In 1970, the poet Robert Lowell took a teaching appointment at Oxford, leaving behind his wife, the critic Elizabeth Hardwick, and the couple’s 13-year-old daughter, Harriet. At a party that spring, he encountered the heiress and Anglo-Irish writer Caroline Blackwood. He moved into her house that night.

Lowell is a complex figure—there are way too many threads to this story than I can get into here. Except to add that Lowell died in a NYC taxi in 1977, en route to Hardwick’s apartment, Lucien Freud’s painting of Blackwood clutched in his arms.

[Now and then, I’m visited by the suspicion that I’ve led rather a boring life . . . ]

Sheila Ballantyne: Somewhere I still have the battered paperback I read in the 70s. Ballantyne published only three books—a book of stories and another novel, Imaginary Crimes (1982).

Her Wiki says her writing “primarily focused on the shifting roles of women during first-wave feminism.” If you’re familiar with late-Victorian novels devoted to the “New Woman” (not to mention the long history of the women’s suffrage movement), calling the 1960s feminism “first wave” seems a misnomer. But it’s true that in the years after Simone de Beauvoir’s landmark The Second Sex (1949) and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), along with other foundational texts, a wave of feminism-infused fiction did appear. A review of Norma Jean . . . linked it to Sue Kaufman’s novel Diary of a Mad Housewife (1967). A few other examples:

The Women’s Room, Marilyn French (1977)

Kinflicks, Lisa Alther (1976)

The Female Man, Joanna Russ (1975)

Fear of Flying, Erica Jong (1973)

Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen, Alix Kates Shulman (1972)

Here’s a bit from a reader’s online review:

I'm reading it for the third time, and it's as fresh, funny, and captivating as it was the first time I read it over ten years ago. Norma Jean is a 30-something, suburban wife and mother of three, struggling to define a life that is her own after 7 years of drowning in the demands of children and babies. Interspersed with Norma Jean's daily trials in the kitchen and carpool, are her dreams, snippets from books on motherhood and Egyptian mythology, and her conversations with the shrink. Ballantyne's skillful storytelling gives us a novel that is both hilarious and profound.

Dorothy Baker: Another important save by NYRB. Surprised to learn that Baker came from Missoula, Montana. Her first novel, Young Man With a Horn (1938)—also NYRB— was based on cornetist Bix Biederbecke. Read about her here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_Baker_(writer)

Moonflower Vine: My wife is one of four sisters, therefore I have a soft spot for four-daughter novels. This is the one I didn’t remember until doing the note on Chase, above.

What I didn’t realize was that this novel was a bestseller when first released . . . and yet fell into obscurity—here’s a link to it a meaty page on it at Brad Bigelow’s Neglected Books blog from 2006:

https://neglectedbooks.com/?p=134Comyns:

Barbara Comyns: Hers is a name I recognized from ads for NYRB titles—they’ve reissued at least three of hers (dates are original publication): The Juniper Tree (1985), The Vet’s Daughter (1959) and Our Spoons Came From Woolworths (1950). That last one must’ve struck me as self-consciously whimsical/cutesy—i.e. not terribly serious, the way Elaine Dundy’s title The Dud Avocado (1958) did—another NYRB reprint. But a recent issue of the magazine (The New York Review of Books) ran a piece on Comyns, “Ducks in the Dining Room,” that vanquished my misperception of her. I’m including a link below—non-subscribers can read it for free by signing in. Or your public library?

Anyway, it’s such a gift to read a writer who’s unpredictable—unpredictable because the mind creating that voice is unique. It’s a book rife with black humor, deadpan, often astonishing images, as in:

Doctor Hatt stood alone like a man in a dream. He seemed absent from his wife’s funeral. The mid-day sun burned down on the black group of people. They looked like bloated, sleepy flies at the end of the season.

Wow, reads my margin note. Three quite-plain short sentences, then a zinger. [The exceptionally devoted among you might remember my note on Manhattan Transfer in Voice [3], an example of dos Passos using the same strategy:

She stood in the middle of the street waiting for the uptown car. An occasional taxi whizzed by her. From the river on the warm wind came the long moan of a steamboat whistle. In the pit inside her thousands of gnomes where building tall brittle glittering towers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Comyns https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2024/03/07/ducks-in-the-drawing-room-barbara-comyns/