Reading the 80s

Good afternoon (evening? morning?). Quick word before today’s post:

As always, heartfelt thanks to new recruits and longtime readers. My pledge: Not to waste your time.

My ongoing ask: If at all possible, go from the email notification to the Substack site, then view the post on a tablet or laptop—otherwise you don’t see it the way I designed it.

On tablet or laptop, the footnotes should pop up with a touch of the cursor (no scrolling down). I hate to think of you skipping the footnotes. The meat’s in the notes (or, alternatively, the plant-based protein). If I embed the commentary in the text, it’s way too messy, and the lists stop looking like lists.

My other ongoing ask: Almost none of you comment or like—maybe it’s simply the nature of the Substack culture, but more interaction/dialog would be (really) good.

See you again in a couple of weeks.

—David

I wanted to follow up last year’s posts—Reading the 1920s and Reading the 1930s—with Reading the 1980s. But, as I discovered, the 80s is another kettle of fish.1

Why so?

For one thing, there are vastly more books to consider, more writers, more genres, more presses, more intel. Beyond that, I was around in the 80s, gobbling up fiction to help me figure out who I might become as a writer.2 Of the 61 books in Reading the 1920s, I’d read only half. I’ve read over two hundred from the 1980s. And though I learned from the likes of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Woolf, Dos Passos, Faulkner, et al, their novels and stories were, to some extent, historical artifacts—I read them the way I read Trollope and Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell, Henry James, Edith Wharton. The 80s writers were my own elders—theirs were the novels and story collections on the new book shelves, the ones reviewed/talked about as I was trying to write my first serious literary fiction. My obligation toward them feels, somehow, different.

About constructing these lists: They begin with what I’ve read and admired; then I tackle my blind spots via research. Though I concentrate on literary fiction, generally skipping horror, romance, non-literary sci-fi, YA, and so on, I try to make the lists more representative—of what was being written, and by whom.

I actually tried this post a year ago, but bailed—way too many books. A list with 100-200 titles might have its uses, but isn’t so hot when you’re looking for the next book to read. It’s like a tableful of ingredients, when what you want is supper.

Also, I realized I’d been avoiding the more basic issue: Do you pluck out the “great books”—the ones time has anointed—novels like The Great Gatsby, To the Lighthouse, or A Farewell to Arms for the 20s, The Grapes of Wrath for the 30s? Or the ones that earned the most money and/or spawned the splashiest films, Gone With the Wind, say?

We recognize decades as eras, swaths of cultural history of a manageable size for talking about. Sometimes the 00s do seem to line up with waves and troughs in the overall zeitgeist. It works for the 30s: The profligate 20s leading to the Crash, the Depression/working-class misery/the rise of socialist sentiment, then the abrupt sea change wrought by WWII. On the other hand, these ten-year chunks lack nuance, and as Milan Kundera says, forgetting begins in remembering—highlight one detail and you sweep a thousand others into the oubliette. I came of age in the 1960s; for later generations, the 60s is beads and headbands and doobies—theme-party stuff. At some point, you realize that unless you were there you get it wrong.

The other day I ran into a LitHub post: A Century of Reading: The 10 Books That Defined the 1980s.3 A couple of Emily Temple’s iconic titles are in my post; the rest aren’t . . . because we have different goals. Hers is to highlight works that illustrate the decade’s principal vibe, mine is to show that despite the faux-clarity time bestows, the decade was messier, more polyglot, and that you get a different story if you zoom out from corporate/New York-based publishing and take in more of our wide world.

By now, you’re wondering if I’ll ever get to today’s list. Relax, almost there.

Here’s the strategy for Reading the 80s:

Three book shelves marked Literary Fiction, Writing Translated into English, and Short Story Collections. The ground rules: No more than three books per year, one book per writer, and no books you won’t be able to lay hands on.

The Translation and Story Collection shelves need no preface.

The Literary Fiction shelf does, as follows:

Each year has one favorite of mine, plus one that’s challenging, and one that qualifies as “speculative”—slipstream/dystopian/alt-world/alt-history/sui generis weirdness, etc. This is what I mean by “challenging”: gritty/not-so-feel-good, not going down the center aisle, morally complex, a bit squirmy/cringey maybe, requiring attentive/nimble reading, and so on. I won’t say which is which . . . one book could be all three.4

And since a main motive behind this post, and David’s Lists 2.0 generally, is to not tell you what you already know, I’ve culled a bunch of great 1980s reads to free up space for books you’re less aware of. See them here.5

Finally, I’ve made no overt attempt at characterizing the 1980s—it feels facile/shallow to talk about Ronald Reagan and Gordon Gecko’s Greed . . . is good.

Let’s let the books speak for themselves.

1. LITERARY FICTION:

1989

Geek Love, Katherine Dunn

The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, Oscar Hijuelos

Hyperion, Dan Simmons6

1988

The Swimming-Pool Library, Alan Hollinghurst

Wittgenstein's Mistress, David Markson7

The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie

1987

1986

The Bridge, Iain Banks [Scotland]

Kate Vaiden, Reynolds Price

Fools Crow, James Welch

1985

Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy

Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English, Ken Saro-Wiwa [Nigeria]

Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, Jeanette Winterson (1985)

1984

Blood and Guts in High School, Kathy Acker10

Neuromancer, William Gibson

The Tie That Binds, Kent Haruf

1983

Pitch Dark, Renata Adler

The Burning Mountain, Alfred Coppel11

Ironweed, William Kennedy

1982

Ham on Rye, Charles Bukowski

The Compass Rose [stories], Ursula K. Le Guin

The Women of Brewster Place, Gloria Naylor

1981

Little, Big, John Crowley

Lanark, Alastair Gray [Scotland]

Good Behavior, Molly Keane12

1980

A Month in the Country, J. L. Carr

Waiting for the Barbarians, J. M. Coetzee [South Africa/Australia]

Riddley Walker, Russell Hoban

2. WORKS IN TRANSLATION:

1989

Like Water for Chocolate, Laura Esquivel [trans. from Spanish by Carol Christensen and Thomas Christensen, 1992]. [Mexico]

1988

Nervous Conditions, Tsitsi Dangarembga13 [Zimbabwe]

Tropical Night Falling, Manuel Puig14 [trans. from Spanish by Suzanne Jill Levine, 1991] [Argentina]

Red Sorghum, Mo Yan15 [trans. from Chinese by Howard Goldblatt, 1993] [China]

1987

Eva Luna, Isabel Allende [trans. from Spanish by Margaret Sayers Peden, 1988] [Chile]

1986

The Beautiful Mrs. Siedenman, Andrzej Szczypiorski [trans. from Polish by Klara Glowczewska, 1989] [Poland]

1985

The Old Gringo, Carlos Fuentes [trans. from Spanish by Margaret Sayers Peden and the author, 1985] [Mexico]

Love in the Time of Cholera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez [trans. from Spanish by Edith Grossman, 1988] [Colombia]

Perfume, Patrick Süskind, [trans. from German by John E. Woods, 1986] [Germany]

1984

The Lover, Marguerite Duras [trans. from French by Barbara Bray, 1985] [French Indochina (Vietnam)/France]

The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera [trans. from Czech by Michael Henry Heim, 1984] [Czechoslovakia/France]

Cities of Salt, Abdelrahman Munif [trans. from Arabic by Peter Theroux, 1987] [Jordan]

1983

Mr. Palomar, Italo Calvino [trans. from Italian by William Weaver, 1985] [Italy]

The Piano Teacher, Elfriede Jelinek16 [trans. from German by Joachim Neugroschel, 1988] [Austria]

1982

A Wild Sheep Chase (1982) [trans. from Japanese by Alfred Birnbaum, 1989] and Dance, Dance, Dance (1988), Haruki Murakami [trans. from Japanese by Alfred Birnbaum, 1994] [Japan]

Baltasar and Blimunda, José Saramago17 [trans. from Portuguese by Giovanni Pontiero, 1987] [Portugal]

1981

Summer in Baden Baden, Leonid Tsypkin18 [trans. from Russian by Roger and Angela Keys, 1987] [USSR]

The War at the End of the World, Mario Vargas Llosa19 (1981) [trans. from Spanish by Helen R. Lane, 1984] [Peru]

1980

So Long a Letter, Marima Bâ [trans. from French by Modupé Bodé-Thomas, 1981] [Senegal]

Woman Running in the Mountains, Yūko Tsushima [trans. from Japanese by Geraldine Harcourt, 2022] [Japan]

3. SHORT STORIES

The Soho Press Book of 80s Short Fiction, Dale Peck, editor (2016)

The Best American Short Stories of the Eighties, Shannon Ravenel, Editor (1990)

1989

Nebraska [stories], Ron Hansen20

Family Sins and Other Stories [stories], William Trevor21 [Ireland]

The Big Mama Stories [stories], Shay Youngblood

1988

1987

Some Soul to Keep [stories], J. California Cooper

The Afterlife: And Other Stories, John Updike

Scenes from the Homefront [stories], Sara Vogan

1986

Burning Chrome [stories], William Gibson

The Progress of Love [stories], Alice Munro

1985

Greasy Lake and Other Stories, T. C. Boyle24

Jewel of the Moon [stories], William Kotzwinkle

1984

Angels Laundromat (1981), Legacy (1983) Phantom Pain (1984), and Safe & Sound (1988), Lucia Berlin [see note25]

Extra(ordinary) People [stories] Joanna Russ26

1983

The Burning House [stories], Ann Beattie

Cathedral [stories], Raymond Carver

Places in the World a Woman Could Walk [stories], Janet Kauffman

1982

Different Seasons, Stephen King [four novellas]27

Man Descending [stories], Guy Vanderhaeghe [Canada]

1981

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love [stories], Raymond Carver28

Ellis Island and Other Stories [stories], Mark Helprin

Sixty Stories, Donald Barthelme

1980

Music for Chameleons [short fiction/reportage], Truman Capote

The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty

1980s pages in the Birth Year Project:

Kettle of fish: Now I could’ve said: a whole different ballgame, a horse of a different color, another thing altogether—all equally trite. However, this way the four or five of you who’ve scrolled down here will get to hear about the orgy of overeating that occurred following my older boy’s wedding in 2003:

Door Peninsula, Wisconsin, top left-hand corner of Lake Michigan. June evening. Naturally, I’d been to fish frys—also crab feeds, lobster feeds, even a smoked-oyster feed . . . but I’d never witnessed a “fish boil.” You know the cartoon with the missionaries in the big cast-iron pot? Like that. Substantial mess of logs underneath, tended by a young kettlemeister who hastens things along with robust squirts of accelerant. In the pot: local whitefish. The wedding party drinks and chats. Suddenly, the cry: Boil over! Boil Over! We flock around in time for the high drama: billows of fishy foam roiling over the cauldron’s rim, hissing down into the flames. Oohs and aahs all around. But then we’re on both sides of long shiny-papered picnic tables, sleeves rolled past elbows. The bonanza of fish is impressive, no doubt about it, but it’s the quantity of melted butter that gobsmacks us. Shouldn’t have, though—this was, after all, Wisconsin.

Who I might become: A writer is a reader moved to emulation. [Saul Bellow]

LitHub:

https://lithub.com/a-century-of-reading-the-10-books-that-defined-the-1980s/

All three: Though not an 80s novel, Cormac McCarthy’s, The Road, would be an example—a novel I revere, that’s a tough read, that’s speculative (post-apocalyptic, in this case).

Culled books/aka My 80s A-List:

The Remains of the Day, Kazuo Ishiguro (1989)

The Joy Luck Club, Amy Tan (1989)

Beloved, Toni Morrison (1987)

A Perfect Spy, John le Carré (1986)

The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood (1985)

Swimming To Cambodia [monolog], Spalding Gray (1985)

The Cider House Rules, John Irving (1985)

Lonesome Dove, Larry McMurtry (1985)

Love Medicine, Louise Erdrich (1984)

Bright Lights, Big City, Jay McInerney (1984)

Cal, Bernard MacLaverty (1983)

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant, Anne Tyler (1982)

The Color Purple, Alice Walker (1982)

Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson (1981)

The Clear Light of Day, Anita Desai (1980)

The Executioner’s Song, Norman Mailer (1980)

So Long, See You Tomorrow, William Maxwell (1980)

Simmons: A lot of us were blindsided by the fact that Simmons turns out to be a far-right-ideolog—generally, I’d suggest steering clear, but he’s an enormously talented writer with range. This novel and the following novel in the Hyperion Cantos, The Fall of Hyperion (1990) are excellent reads—a far-future take on The Canterbury Tales. Inventive, humane, deeply engaging.

Markson: As my long-time followers know, I’m a big-time fan of his Notebook Quartet. This is nothing like those books [which are, themselves, not like anything]. Well, this one isn’t like anything, either . . . unless it’s Anna Kavan’s, Ice (1967). It’s a WTF novel . . . about a woman who might or might not be the last woman on Earth.

https://thinkinthemorning.com/random-thoughts-on-david-marksons-wittgensteins-mistress/

Octavia E. Butler: A prolific, foundational writer of feminist sci-fi/speculative lit. MacArthur “Genius” recipient. She wrote a number of series. This novel is the first of the Lilith’s Brood or Xenogenesis Trilogy. Kindred (1979) and The Parable of the Sower (1993) are often recommended as good entry points to her body of work.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Octavia_E._Butler

Lively: The 1987 Booker Prize, winner.

Acker:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathy_Acker

The Burning Mountain: Alternate history. The novel’s subtitle is A Novel of the Invasion of Japan. The premise is that the U.S. atomic bomb test fizzled, necessitating a land invasion. Seen from the POV of soldiers from both sides; based on de-classified documents (from both sides). Coppel was a WWII fighter pilot who became a prolific writer of pulp sci-fi under several pseudonyms. This one seems to be a cut above, based on many reader reviews.

Keane: Here’s the footnote on her from Sixes [1]: . . . just read this one and it’s pretty delicious. The title is like a faceted stone—depends on which direction the light’s coming from. Note: Don’t let the fact that the narrator may have murdered her mother in the opening pages stand in your way, OK?

Keane was Irish. Her real name was Mary Nesta Skrine, but published her novels and plays under the name M. J. Farrell. She married Bobby Keane in 1938, and they had two daughters. Then, in 1946, the husband died suddenly, her most recent play flopped, and she published nothing for the next twenty years. Only then came Good Behaviour, the first work to appear under her own name.

Nervous Conditions: This novel was written in English—the first to be published in English by a Black woman from Zimbabwe. Named by the BBC as one of the top 100 books that have shaped the world, 2018. She’s also a playwright and filmmaker.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nervous_Conditions

A later novel, This Mournable Body (2018), has appeared in a couple of prior posts:

Puig: Best known for The Kiss of the Spider Woman (1976).

https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2368/the-art-of-fiction-no-114-manuel-puig

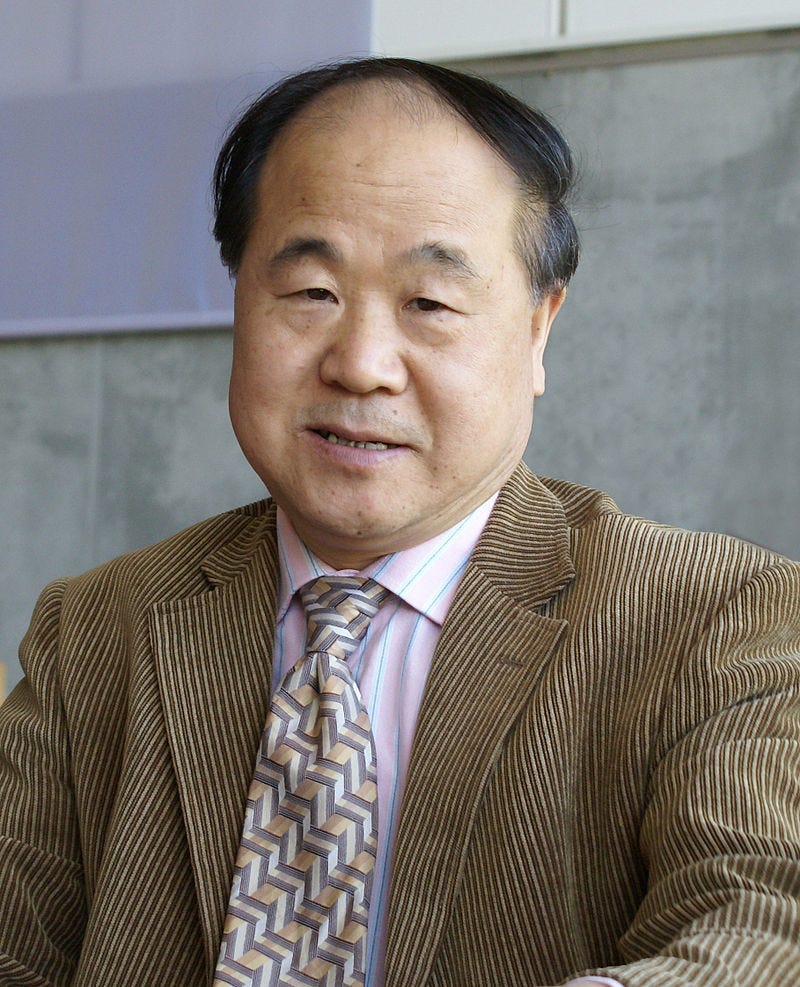

Mo Yan: 2012 Nobel Laureate in Literature. Mo Yan is a pen name meaning “Don’t speak.” Local history with big doses of magical realism and black humor. See also The Garlic Ballads (1988) and Life and Death are Wearing Me Out (2006). Works often banned and pirated.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mo_Yan

Jelinek: 2004 Nobel Laureate in Literature.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elfriede_Jelinek

Saramago: His 1995 novel, Blindness, is in my personal pantheon. The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1984) is also good (it helps to know that Ricardo Reis is the name of one of Fernando Pessoa’s truckload of pen names/heteronyms. [Pessoa’s odd assemblage of fragments, The Book of Disquiet, was first published decades after his death in 1935.] In Saramago’s novel, as I remember it, Reis is unaware of being a character in a book.

Saramago’s novels after Blindness weren’t as compelling IMHO—too dependent on some weirdness/Macguffin/plot twist (as in the films M. Night Shyamalan made after The Sixth Sense).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jos%C3%A9_Saramago

Summer in Baden-Baden: From Wiki:

. . . a fictional account of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's stay in Germany with his wife Anna. Depictions of the Dostoyevskys' honeymoon and streaks of Fyodor's gambling mania are intercut with scenes of Fyodor's earlier life in a stream-of-consciousness style. Tsypkin knew virtually everything about Dostoyevsky, but although the details in the novel are correct, it is a work of fiction, not a biographical statement.

Also a doctor. Read about his life under Soviet authorities:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonid_Tsypkin

Vargas Llosa: 2010 Nobel Laureate. Influential member of “El Boom” (aka The Latin-American Boom), prolific, long-lived (he died in April of this year). Also a Peruvian political figure since the 1960s.

htps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mario_Vargas_Llosa

Other major works:

The Feast of the Goat, Mario Vargas Llosa (2000)

Death in the Andes (1996)

In Praise of the Stepmother (1990)

Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1982)

Hansen: “Nebraska” and “Wickedness.”

Trevor: He also wrote novels, but you should read at least one of his short stories. He’s a great example of old school, quietly precise, understated but steeped in a mature sense of lived life—truly a master.

Salter: Another absolute master. “Dusk” and “American Express” are commonly pointed to, but see if you can find “Twenty Minutes.” Devastating.

The Assignation: This is a lesser-known collection; many qualify as flash fictions, and several are perfect examples of the genre—”A Touch of the Flu,” for one.

T. C. Boyle: Early work, before all the novels. It’s here because it contains “The Hector Quesadilla Story,” about an aging ballplayer, a pitcher, with a prodigious appetite. You can find a reading of it in a download from Symphony Space/Selected Shorts:

https://store.symphonyspace.org/products/the-hector-quesadilla-story-by-t-c-boyle-mp3-download

And, I just discovered, you can read it in the Paris Review’s archive:

https://www.theparisreview.org/fiction/2958/the-hector-quesadilla-story-t-coraghessan-boyle

Berlin: Wiki’s opening note about her:

She had a small, devoted following, but did not reach a mass audience during her lifetime. She rose to sudden literary fame in 2015, eleven years after her death, with the publication of a volume of her selected stories, A Manual for Cleaning Women. It hit The New York Times bestseller list in its second week, and within a few weeks had outsold all her previous books combined.

Another best-of appeared in 2018: Evening in Paradise: More Stories.

The four collections I cite aren’t easily found; the posthumous ones reprint stories from them and are readily available. Highly recommended.

Russ: Early feminist sci-fi.

https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/joanna-russ-science-fiction/

King: Less horror-oriented than his later collections. This one contains “The Shawshank Redemption.”

https://reedsy.com/discovery/blog/stephen-king-short-stories

Carver: The most iconic short fiction writer of his time. I can’t do justice here to all that should be said about him—especially his relationship to editor Gordon Lish. He was a self-taught, blue-collar guy, who wrote in a non-literary voice (if that makes any sense at all). He was widely copied by a generation of MFA students and others—who, naturally, got it all wrong. Carver’s voice came from Carver and there was only one Ray Carver. If you try to copy another’s voice all you get is gold gilt, about a milli-micron thin. Carver’s way of expressing his view of things, his big-heartedness, was his own. The terseness you observe in his early stuff came, in part, from Lish’s radical editing—some of the stories, notably “A Small, Good Thing” were restored to their fuller iterations when reprinted. [You can find this sort of thing in early Faulkner as well—his third novel was rejected, a piece was salvaged and published as Sartoris (1929). Not until 1973 was the restored text published with its original title, Flags in the Dust. It’s very good, damn funny in spots.

Back to Carver: You can read the stories, but it’s good to know more about the arc of his life and his writing life. He died way too young—at fifty, having gotten sober, remarried (to poet Tess Gallagher) and gotten to a fuller and more recognized position in the literary world. He was capable of an enormous compassion, big-heartedness, grace. His last poem, “Gravy,” published in The New Yorker, is testimony—no bitterness at being cheated of life. It ends:

“Don’t weep for me,”

he said to his friends. “I’m a lucky man.

I’ve had ten years longer than I or anyone

expected. Pure gravy. And don’t forget it.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Carver

I loved Mambo Kings!

If I had started reading Kent Haruf with The Tie That Binds I might not have bothered to read his later work—just wouldn’t have been impressed. But I started with Plainsong, and then went back to read the earlier novel. Realized, ah, that’s where he started. (Am I making sense?)