Friends: Back from Lake Superior. Read John Crowley’s Little, Big (1981), H. W. Brands’ Our First Civil War: Patriots and Loyalists in the American Revolution (2021) and Octavia E. Butler’s The Parable of the Sower (1993).

A reminder that the Birth Year Project is still active. Link to the most recently posted year, 1945.

Reminder, as well, that a) this Substack is best viewed on a laptop, or at least at the Substack site, and b) I try to keep the lists looking list-like, which means most of the commentary is in the footnotes.

As always, thanks for your loyalty. It would be great to add a few more subscribers/followers (free to everyone).

I promise not to waste your time.

Clusters, Chains

Part One:

Trading ideas with a fellow Substacker, found myself musing about how we go from book to book. We have two strategies, it seems: chance/spur-of-the moment and organized/purposeful.

So that’s today’s subject.

First, a warming-up exercise:

[Note: If you keep track of your reading1, this will be easier. If not, try to reconstruct a string of half a dozen books you’ve read, in the order you read them.]

Take a sheet of unlined paper, draw a box big enough to write a book title in and enter Book 1. Draw another a couple of inches from the first, write in Book 2, then draw a line connecting them. Along the line, try to say why you picked the second book. Then do the rest. Be honest, specific [no one will read this but you]. Here’s the kind of thing you might say:

X was the next book in the Y series—I was hot to keep going.

Was reading a lot of [genre/mood/period/gender] books and wanted something completely different.

I’d finished an historical novel set during the Civil War and wanted to try one written during that time.

Margo lent me this. She reads weirder stuff than I to, but I wanted to tell her I’d read it . . . actually I was surprised how much liked (most of) it.

Was focusing on translated novels and wanted a country/language I’d never read.

I don’t read [sci-fi, cli-fi, dystopian, fantasy] but X sounded intriguing so I took a chance on it.

Was headed to the restroom at the library and the title on spine jumped out at me.2

Or who knows? But see if you can repeat this for the other reads, 6-8, say. Maybe you’ll see a pattern, maybe not. Pay special attention to times you interrupted your queue to read something else. These chains are snapshots of your reading life—they can help to fine-tune your sense of who you are as a reader.

Two Notes:

Some readers read according to whim/happenstance/availability/etc. their entire reading lives. Do not take today’s post as gainsaying that style. Chance has its delights, after all.

Some clusters/chains in this post have more to do with the writers’ lives/eras, some with the books’ contents—theme/voice/structure/etc. Both kind can be illuminating.3

Part Two:

I named this post Clusters & Chains because organized reading schemes take one of these two shapes.

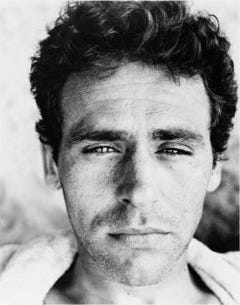

I’ll start with a cluster from much earlier in my reading life. It started with a fascination with Walker Evans’ photographs.4 That led me to his work documenting the rural relief programs of FDR’s New Deal.5 In 1936, Evans partnered with writer/screenwriter, James Agee, to produce a piece on sharecroppers for Fortune magazine. The magazine declined it, but it morphed later into one of the great sui generis mid-century works, Now Let Us Praise Famous Men.6

My cluster:

Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye, Gilles Mora, John T. Hill, Walker Evans (1993)

Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties, Forrest Jack Hurley (1972)

A Death in the Family, James Agee (1957)7

Now Let Us Praise Famous Men, James Agee and Walker Evans (1941)

Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck (1939)

[Note: Looking at this material again for today’s post, I found criticism of Stryker’s methods I’d not seen the first time, such as Mind’s eye, mind’s truth: FSA photography reconsidered, James Curtis (1989), and several journal articles.]

One more quick example, then some ideas for you.

David’s Lists 2.0 junkies will recognize the name, Caroline Blackwood. [See footnotes 5 & 6 in Sixes [1]. Also note (neat overlap), the photo atop that post was taken by Walker Evans.] As I mentioned at some point after reading a bit about who she was, I read a biography of her by Nancy Schoenberger, Dangerous Muse.

Robert Lowell was a major mid-century American poet, first married to writer Jean Stafford, then to writer Elizabeth Hardwick. He moved his family (with Hardwick) to London for a teaching gig, met Blackwood at a party in April 1970, and (I’m not making this up) moved in with her that same night. So, a potential cluster:

The Dolphin: Two Versions 1972-1973, Robert Lowell (ed. by Saskia Hamilton, 2025)

The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979: Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell, and Their Circle, Saskia Hamilton, ed. (2019)

The Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick (posthumous, Darryl Pinckney, ed., 2017)

Why Not Say What Happened? [memoir], Ivana Lowell (2010)

Never Breathe a Word: The Collected Stories of Caroline Blackwood [nonfiction] (2010)

Dangerous Muse: The Life Of Lady Caroline Blackwood, Nancy Schoenberger (2002)

Sleepless Nights [novel], Elizabeth Hardwick (1979)

Great Granny Webster, Caroline Blackwood (1977)

Part Three:

A small heap of Cluster/Chain ideas:

Even if you mainly read fiction, read a nonfiction work that has a Bibliography/Further Reading section in back. Could be literary—I liked Rosemary Ashton’s 142 Strand: A Radical Address in London8 —or science-y, social historical . . . could be the evolution of an idea or practice or degree of understanding of a phenomenon over time, you name it. When you’re done with that book, pick another from the Further Reading. Do same again. See how far you can keep the chain going. You’ll amaze yourself, guaranteed.9

Montana Women Writers, by decade.10

If you’ve never read African lit, try starting with Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958), then come forward gradually, 5-8 books? Maybe include some of these.11

An idea I’m stealing from a post-in-the-works: Our attention to books in translation usually focuses on: a) the book, or b) the country it’s from. Here’s a c): Locate a translated book you consider lucid/well-voiced, etc., look up the translator. Presses like Charco, Deep Vellum, NYRB, Europa Editions, and many others often have multiple titles by a given translator. Zero in on one translator and follow their work through 5-7 books.12

Make a chain of books showing an idea/practice/technology/understanding of some phenomenon morphing over a period of years. Lots of room for experimentation here; try to integrate fiction/nonfiction/memoir/biography—in other words, come at the centerpoint from all directions.13

Make a cluster of novels showing people at the cusp of enormous cultural/political upheaval—such as war, expulsion from homeland, etc. (real-world stuff, not fantasy/speculative/dystopian/apocalyptic stories).14

And finally: Here are four novels that mess with space, or let’s say spatial dimensions in one way or another:

Houses of Ravicka, Renee Gladman (2017)

The City & the City, China Miéville (2009)

The Raw Shark Texts, Steven Hall (2007)

House of Leaves, Mark Z. Danielewski (2000)

See if you can identify others (3-5?). Build a cluster and read.

Part Four:

The project/challenge is ultra simple: Design then read a cluster or chain.

No other rules.

Some of you already do structured reading every now and again. Others don’t get off on this sort of thing—too fussy, too non-spontaneous, etc. (I can picture a few of you going, Well, hey, I’ve fended off Reading Challenges [1-21]—why ruin my streak??)

It’s all good. We don’t do arm-twisting here at David’s Lists 2.0.15

My own thinking: the structure of a project frequently blindsides you with reading you’d never have otherwise bumped into. It’s a bit like writing a sonnet: the limitation of needing a rhyme word can lead to a stunningly original statement.

Also (gotta say it) coming from New England, I believe projects are good for you, per se.

Good luck. Thanks for sticking around. See you in a couple of weeks.

Keeping track: As you might suspect, I’m a big fan of this. I started writing down what I read each month back in 1979 [sheet of yellow tablet pushpinned to wall, then a binder], later started adding [Tr] for translations, [R] for re-reads, [Sp] for speculative, etc. Later still, put it all into a Word file [alphabetical by year published, newest to oldest]. My wife believes I have . . . well, a disorder of some kind.

Headed to the restroom: In my case, Berton Roueché’s, Eleven Blue Men (1953). How can you resist that title? Turned out to be pieces he wrote for The New Yorker—precursor to the column later dubbed “Annals of Medicine.” I’d tell you why the men were blue but that would spoil the fun.

My old page [Facebook] was just book lists. Some, while fun to build, lacked even a whiff of gravitas. “Ordinal Sins,” for instance . . . went from The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August and The Second Coming to The Fifth Child, The Thirteenth Tale, The Twenty-Seventh City, up to The Last Tycoon, The Last Thing He Wanted, The Last Days of New Paris, The Last Fine Time . . . and so on.

Substack’s more expansive/flexible format has let me talk about the books; the lists have gotten less superficial, more useful (or that’s my hope). Therefore, no more frivolous stuff like Books with Blue in the Title.

Oh hell:

A Spool of Blue Thread, Anne Tyler (2015)

Blue Nights [memoir], Joan Didion (2011)

Bluets [memoir], Maggie Nelson (2009)

The Blue Place, Nicola Griffith (1998)

Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space [nonfiction], Carl Sagan (1994)

Nothing But Blue Skies, Thomas McGuane (1992)

A Yellow Raft in Blue Water, Michael Dorris (1987)

Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, Tom Robbins (1976)

The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison (1970)

“Sonny’s Blues” [short story, Going To Meet the Man], James Baldwin (1965)

Eleven Blue Men [reportage], Berton Roueché (1953)

Walker Evans:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walker_Evans

https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/walker-evans-1903-1975

New Deal Relief Program: Under the guidance of The Farm Security Administration, led by Roy Stryker [within the Department of the Interior].

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/e5462600-c5d9-012f-a6a3-58d385a7bc34

A Death in the Family: Yes, read the novel [it won the Pulitzer]. But I want to call your attention to a short piece, often (but not always) included as a prolog to this novel, though written earlier (1938), “Knoxville: Summer of 1915.” Stunningly beautiful.

Samuel Barber used it as the text in a work for orchestra and voice first performed by the Boston Symphony in 1948.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knoxville:_Summer_of_1915

142 Strand: The hangout of mid-century Victorian writers, the offices of The Westminster Review, where Mary Ann Evans became George Eliot, etc. An excellent reminder (for me at least) that we didn’t invent coteries of passionate young writers, disdainers of outdatedness, prudery, monogamy, etc.

Further Reading: My wife, a retired medical librarian, is a master of this art. Her fascination with Siberia led to a menagerie of texts, new and old, some way off the beaten path. She turned me onto a book I love and have pitched in DL2.0 a couple of times: Tent Life in Siberia, a memoir by George Kennan (1870)—Kennan was, BTW, a shirttail ancestor of 1950s Cold War diplomat, George F. Kennan. Here’s my earlier note:

The first attempt to lay a telegraph cable across the Atlantic having failed, the American Telegraph Company hatched a scheme to string wire from the Bering Straits across Siberia to Europe; Kennan and his team spent a couple of years plotting the route, securing timber, enduring insanely challenging conditions, but (the book’s triumph) he details as well their interactions with native, often nomadic, populations. A fascinating read. (Word eventually reached them that a second try at the Atlantic cable had succeeded; the whole Siberia project collapsed, virtually overnight.)

Montana Women Writers:

This Is Not the Ivy League [memoir], Mary Clearman Blew (2013)

Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It [stories], Maile Meloy (2009)

Montana Women Writers: A Geography of the Heart, Caroline Patterson, ed. (2006)

Breaking Clean [memoir], Judy Blunt (2002)

Perma Red, Debra Magpie Earling (2002)

Winter Range, Claire Davis (2000)

Some Went West [nonfiction], Dorothy M. Johnson (1997)

Homestead [memoir], Annick Smith (1995)

One Sweet Quarrel, Deirdre McNamer (1994)

In Shelley’s Leg, Sara Vogan (1981)

Winter Wheat, Mildred Walker (1944)*

Black Cherries, Grace Stone Coates (1931)

The Story of Mary MacLane [memoir] (1902) [Read about her, I dare you.]

[*Can’t footnote a footnote, but . . . Mildred Walker was married to Great Falls surgeon Ferdinand Schemm, became the mother of writer/poet Ripley Schemm who, later in life, married Northwest poet, Richard Hugo, one of my long-ago mentors.]

African writers: Here’s a few well-known choices to start with:

Tram 83, Fiston Mwanza Mujila, (Democratic Republic of Congo (2014)

The Barefoot Woman, Scholastique Mukasonga (Rwanda, 2008)

Cockroaches [memoir], Scholastique Mukasonga (Rwanda, 2006)

Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimananda Ngozi Adichie, (Nigeria, 2006)

Broken Glass, Alain Mabanckou (Republic of the Congo, 2005)

Nervous Conditions, Tsitsi Dangarembga (Zimbabwe, 1988)

So Long a Letter, Mariama Bâ (Senegal, 1980)

A Season of Migration to the North, Tayeb Salih (Sudan, 1969)

A Grain of Wheat, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (Kenya, 1967)

https://medium.com/bookish-phdlife/list-of-novels-by-authors-from-every-african-country-c5f1c044f803

Translators: You probably do this already, but (especially with iconic texts from the past), check out what the hive mind has to say about the translations. Before I read Les Misérables, I researched how readers felt about the available versions (translators have different biases, different principles driving their work); I picked Julie Rose’s 2008 translation, widely praised for capturing Hugo’s tone and power—I loved it.

Also, it probably goes without saying, that some classic translations (often free for Kindles and the like) have become woefully outdated, or have characters using, say, old British slang for Russian characters that clangs in your ear. Recent books mostly have only one edition, but for those in the deeper past this is an important issue. There are, without doubt, scads of former students who “hated” a great writer due to a bad/bowdlerized/stuffy rendering into English.

Idea/etc. chain: I was thinking about the development of germ theory, remembered a fact my wife told me: in the mid-1800s someone realized infant/mother mortality rates were lower when a midwife assisted in the delivery, rather than a medical doctor. The cause: midwives washed their hands.

Anyway, as I say, endless possibilities—the evolution of obscenity/obscenity laws in literature; the grunge/riot girrl movement in the PNW; atheism/free thinking in pre-20th C. literature; the struggle between “Patriots” and “Loyalists” at the time of the American Revolution (I’m working on this myself). And so on. What nooks and crannies can you let some light into? Don’t make your subject too broad, keep prying. Maybe you’ll find that your thing is too trivial, or there’s not enough writing to make a cluster/chain, but hang with the idea a bit longer and you often find something cool off to the side.

[Old Steven Wright joke: I’m a peripheral visionary. (Pause.) I can see the future but way off to one side.]

Cusp: It occurred to me that three of the books I’d read recently had this in common:

The Singapore Grip, J. G. Farrell (1978) [Third of his Empire Trilogy—the Malay Peninsula, the last days before the Japanese military take over Singapore.]

The Great Fortune, Olivia Manning (1960) [The first of her Balkan Trilogy—a newly married English couple in Budapest as WWII arrives; these characters are followed through this trilogy and the one that followed, The Levant Trilogy, known collectively as The Fortunes of War.]

Transit, Anna Seghers (1944) [Nazi Germany] [Another great save from New York Review of Books Press.]

Arm-twisting: Just a wee smidgen of shaming now and again . . .

David, a couple reflections on this interesting post of yours.

I discovered James Agee a decade or so ago, because I’d heard "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men" was worth checking out. I found it odd, hard to connect with at first, and then by halfway through I realized I was more connected to the family he was reporting on than to any characters in fiction I could recall. A really stunning way of affecting the (at least this) reader. Certainly, Walker Evans’s photographs assisted. That took me of course into Evans’s work, but also into trying to learn what happened to the family after Agee and Walker’s book. As I recall, it continued to be a hard life in new ways as the century moved on.)

Like you, I followed "…Famous Men" with "Grapes of Wrath." As a fan of Samuel Barber’s work, as well as Agee’s, I’ll make a discontinuous chain/cluster (years later) and check out A Death in the Family as well as Knoxville: Summer of 1915 in both written and musical form. Thanks for the tip!

Elizabeth Hardwick: Lauren Groff reads Hardwick’s story “The Faithful” (which I think is taken from "Sleepless Nights") and discusses Hardwick and the story, on “The New Yorker: Fiction” podcast, August 1 episode. I found it a fascinating story from a craft perspective and a very interesting discussion about the author and her life.

Thanks for sharing your insights, and your encouragements to read!

Why an interesting way to build a reading list! Start with Things Fall Apart and Half of a Yellow Sun is one way to go (other African authors), but I could chose non-western nationals talking back to European imperialism, or books revealing non-European culture (I'll pitch for Nectar in a Sieve, which I read first as an adolescent and reread recently with pleasure), or books about that period of time or written during the time it was written, or written by authors exploring their own family history.

For that last, nonfiction The Cost of Free Land by Rebecca Clarren explores the history of her Jewish ancestors fleeing Russian pogroms who settle in South Dakota on land stolen from the Lakota people, "examining themes of inheritance, oppression, and the need for reconciliation. The book highlights the personal and national consequences of this legacy and encourages readers to reflect on their own roles in historical injustices." I appreciated it far more than Isabel Wilkerson's book, which made a good movie.