Reading Project [9]: You Are What You Read

Twenty Books That Shaped Me

Alice Munro, 2013 Nobel Laureate in Literature

[Note: Put cursor over footnote for pop-up.]

Reading Project/Challenge:

Today’s project focuses not on what you promise to read, but on what you’ve already read.

Out of the X-thousand books you have under your belt, some had an out-sized role in making you who you are.

Which ones are they?

Make a list of no more than twenty—not your favorite books, not the kind of inspirational texts anyone might name, but your own formative books, the ones that joggled you, that altered your direction of travel.

Then see if you can say why for each in one or two sentences.

Doing this exercise myself, I was surprised-but-not-surprised how few women writers there were, roughly one in five. No doubt a reflection of when I was born and how I was educated. That said, as I’ve aged, the balance has gradually shifted—these days the novels I read are likely written by women.

It occurs to me, happily, that your roster will be wildly different from mine . . . more politics maybe, more from the culture wars, more having to do with race, more from the rest of the world . . . not to mention all the great lit not-yet-written when I was in my tender years.1

My List:

All Alice Munro short stories (1968-2014)23

All John Updike short stories (1959-2013)4

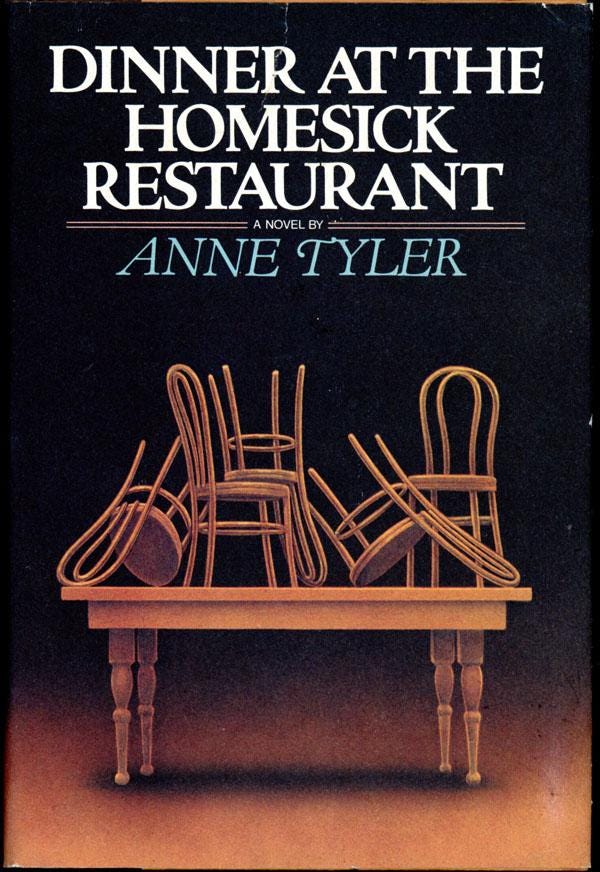

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant, Anne Tyler, 19825

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love [stories], Raymond Carver, 19816

So Long, See You Tomorrow, William Maxwell, 19807

Suttree, Cormac McCarthy, 19798

Of Woman Born: Motherhood As Experience And Institution, Adrienne Rich (1976)9

The Lady in Kicking Horse Reservoir [poems], Richard Hugo (1973)10 11

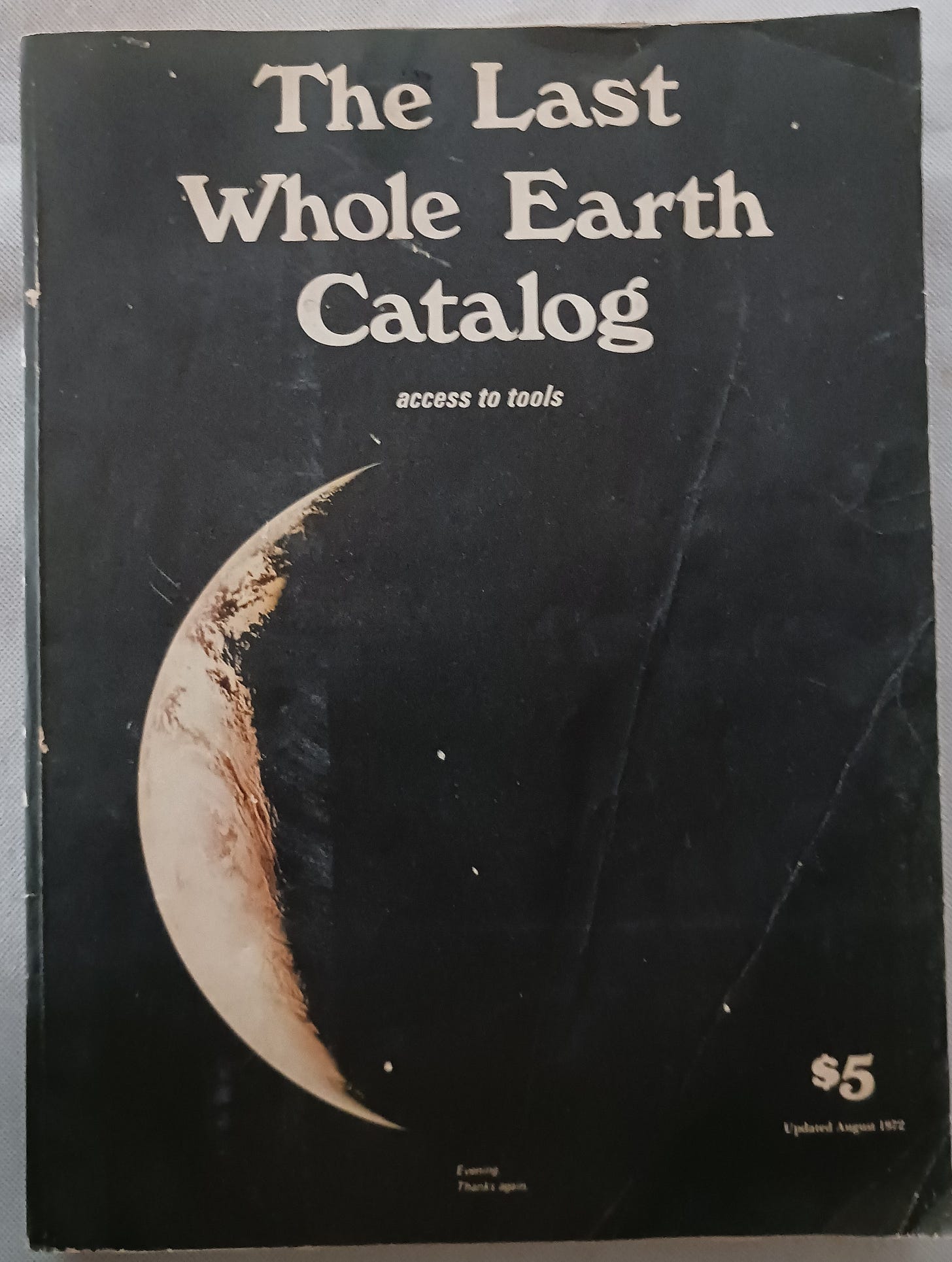

The Last Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand [ed.] (1971)12

Collected Poems, James Wright (1971)13

Trout Fishing in America, Richard Brautigan (1967) 14

Winter News [poems], John Haines (1966)15

Collections of Cartoons from The New Yorker (1950-1966)16

Labyrinths [stories], Jorge Luis Borges (1964)17

Silence in the Snow Fields [poems], Robert Bly (1962)18

The Sacred and the Profane [nonfiction], Mircea Eliade (1961)19

What the Buddha Taught [nonfiction], Walpola Rahula (1959)20

The Poetics of Space [nonfiction], Gaston Bachelard (1958)

The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway (1938)21

Exile’s Return [memoir], Malcolm Cowley (1934)22

As I Lay Dying, William Faulkner (1930 )23

Are you giving this post a quick skim on your phone? I get it. It’s a fraught world, so much that needs doing, so many time-thieves. Then again, maybe you’re one of the ones who thinks, Huh, kind of an interesting exercise . . . wonder which books worked on me like that? And actually tries it.

The first two aren’t specific titles, but stories scattered throughout their published work.

Munro: My hero. She taught me to go sideways as I went down the page. She taught me candor. Read the ending of “Miles City, Montana.”

[And yet, as with so many who influence you, the influence is . . . well, suffusive (I had to look to see if this is even a word). My story writing was my story writing before Munro, and still was afterward, but from then on I was driven by her example, her craft, her persistence, though it’s hard to say (with minor exceptions) exactly what I took from her. Somehow, it feels like (in the gym on a rainy day) she picked me for her dodgeball team, after which I stood with a few others on her side of the half-court line, hoping I’d play well and not let her down.]

Updike: Also my hero, as a story writer. As a novelist, less so, in the sense that he wrote too many books. Some he should’ve thought, Nah, maybe not such a hot idea, after all. But the man could write sentences. My third book of stories, Blue Spruce (1995), was given an award by the American Academy of Arts & Letters; at the luncheon on the Upper West Side, they brought Updike over to shake hands with me. (Before she became my friend, Laura Hendrie won the same award the prior.)

Later, in the back row of risers on stage I sat between Cynthia Ozick and Ann Beattie. We listened to a long-winded, not-fascinating address by an esteemed scholar/member of the academy; partway through, Ann leaned over and whispered into my ear, I am going to kill myself.

A moment I treasure.

Tyler: This was the one that hooked me on Anne Tyler, but also on a certain kind of novel—humane, not-terribly dramatic, centered on private life, featuring good-hearted but often somewhat lost characters (like Ezra in this book). I’m surprised to find this was Tyler’s ninth novel—I was later to the game than I’d thought. She’s published fourteen since then, including The Accidental Tourist (1985), which became a film with William Hurt. She won a Pulitzer for Breathing Lessons (1988), and she’s been a finalist for the other major fiction awards multiple times. Her most recent novel, French Braid—best-seller, enthusiastically received far and wide—came out in 2022, when she was eighty-one.

Carver: Too much to say about Carver for this little space. He unwittingly engendered a cadre of imitators, so-called trailer park realists—they suffered from what the French call nostalgie de la boue [nostalgia for mud], “the attraction to low-life culture, experience, and degradation . . .” There was nothing faux about Ray, though—he was of the world he wrote about; there was no pandering. If you’re interested, you can read about the impact of editor/writer Gordon Lish on the pared-down style that dominates this collection. Ray spent the final chunk of his short life (dead at fifty) sober, at the top of his art, the later work revealing more palpably his connection to the great story writers, especially Chekhov.

Maxwell: In an earlier post I described meeting Maxwell—can’t find it, so I’ll take another stab:

Earlier, the day I met Updike, I had a few moments with William Maxwell. He was about sixty then—rather short, rather dapper, Midwestern-born, long-time New Yorker fiction editor . . . I stumbled all over myself trying to convey my admiration; he managed to put me at my ease.

Sad as it is, I loved this novel from the get-go—the wisdom of the voice, the way the writing feels saturated with the details of lived life . . .

Suttree: I said not to put down your favorite book, but this is my favorite [along with Maxwell’s above]. It’s hilarious, sad, rich in the textures and weights of the world, terse at times, over-the-top at times, deeply human. But it’s a book I don’t recommend willynilly; McCarthy’s writing isn’t for the many. I have yet to read The Passenger (2022), but I gobbled up the companion piece, Stella Maris. And I believe The Road (2006) will be read as long as there are books and readers.

Rich: I’ll let this book represent my opening to feminist theory. I knew Rich as a poet but her discussion of male power vs. female power was transformative, and coincided with the views I acquired from my wife’s boots-on-the-ground involvement with women’s issues.

Hugo: People came to Montana’s MFA program to study with Dick . . . but I had no awareness of his work when I showed up in Missoula in the fall of 1972. He and Bill Kittredge and Madeline DeFrees soon became my primary mentors. I’m letting this collection stand for all the others because it came out when I was his student. I love the stuff in What Thou Lovest Well, Remains American (1975) especially [see next footnote].

All through my life as a fiction writer I’ve been influenced by his angles on craft—from workshops and from his book, The Triggering Town: Lectures and Essays on Poetry and Writing (1979). I’ve lived in the Seattle area for the last twenty-some years and feel his presence everywhere—so many of the names I first ran into in his poems. He was Theodore Roethke’s student, which we also revered him for, then we were his, and our students have soaked up his influence through those of us who have taught writing.

He had a phony bluster, ala Jimmy Cagney movies, but he was truly big-hearted. He named the ex-cop in his one detective novel, Death and the Good Life (1981), Al “Mushheart” Barnes. He was a great teacher; in workshop, when we’d said everything worth saying, he’d go, “Well, we’re just picking the flyshit out of the pepper now.”

Thanks, Dick.

A Snapshot of the Auxiliary

In this photo, circa 1934,

you see the women of the St. James Lutheran

Womens Auxiliary. It is easy

to see they are German, short, squat,

with big noses, the sadness of the Dakotas

in their sullen mouths. These are exceptions:

Mrs. Kyte, English, who hated me.

I hated her and her husband.

Mrs. Noraine, Russian, kind. She saved me once

from a certain whipping. Mrs. Hillborn,

Swedish I think. Cheerful. Her husband

was a cop. None of them seem young. Perhaps

the way the picture was taken. Thinking back

I never recall a young face, a pretty one.

My eyes were like this photo. Old.

This one is Grandmother. This my Aunt Sarah,

still living. That one—I forget her name—

the one with maladjusted sons. That gray

in the photo was actually their faces.

On gray days we reflected weather color.

Lutherans did that. It made us children of God.

That one sang so loud and bad, I blushed.

She believed she believed the words.

She turned me forever off hymns. Even

the good ones, the ones they founded jazz on.

Many of them have gone the way wind recommends

or, if you're religious, God. Mrs. Noraine,

thank the wind, is alive. The church

is brick now, not the drab board frame

you see in the background. Once I was alone

in there and the bells, the bells started to ring.

They terrified me home. This next one in the album

is our annual picnic. We are all having fun.

[in What Thou Lovest Well, Remains American, by Richard Hugo (1975)]

Whole Earth: A few years ago, I wondered what had become of Stewart Brand, prime mover behind the Whole Earth Catalog, the manual for how to do things if you were attempting to live a righteous countercultural life. I found he’d become the prime mover behind the Long Now Foundation—having to do with long-term thinking [one of their projects is a “ten-thousand year clock”] . . . a really interesting nexus of ideas I recommend to you: https://longnow.org/

The Last Whole Earth Catalog could be found on everyone’s shelf.

Does it seem quaint now, a tattered relic of Boomer culture? It’s a reminder to me that whenever you see statements about a decade’s aura/style/belief system, they’re outsiders’ angles, and wrong—primarily because they look at the surface artifacts without really getting what they meant.

Wright: When I was a poetry student in the early 1970s, we all loved “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota” with its naked-yet-enigmatic last line: “I have wasted my life.”

So many other great poems. “A Blessing,” “Autumn Begins in Martins Ferry, Ohio,” “Small Frogs Killed on the Highway,” “In Response To A Rumor That The Oldest Whorehouse In Wheeling, West Virginia, Has Been Condemned” . . .

Trout Fishing: I read Brautigan’s books as they came out, though (as with Vonnegut) I found some of the later books thin, less charming. But for years I revered this one, considered it the quintessential text of countercultural imagining. When I came to know more about Brautigan’s sad life/death, I better understood the fact that he was a serious literary writer with his own talents and demons, and that the hippie patina was just that, a coating put on the work by others. I have no idea what a modern reader, coming to Brautigan cold, would make of him.

[I once had the idea of having a one-night event/benefit (for a library, say) where a bunch of writers read Trout Fishing aloud, tag-team fashion. Never did it. Sigh.]

Haines: Stumbled onto this at the Hartford Public Library the winter of 1970-71. The stark simplicity won me immediately. Also, The Stone Harp (1971). I had no idea that I would soon move to Missoula, Montana, later invite Haines to a literary festival, and get to know him. Nor did I know I’d start writing my first master’s thesis on his work within a few months of that evening in the library.

New Yorker cartoons: The friends of my folks often had one of the cartoon collection on a bookshelf. They were formative. Here’s the earliest one I can remember loving:

My relationship to The New Yorker cartoonists is deeply entrenched. George Price, George Booth, Danny Shanahan, Harry Bliss, Matthew Diffee, Sam Gross, Roz Chast, William McPhail . . . so many others, new and old.

Borges: While Tyler and Munro and Updike fed my hunger for finely observed realism, Borges exemplified the power of the mind, the lure of the arcane.

He was a major figure in Latin American literature, an inspiration to what’s known as the Latin American Boom, which produced the likes of Garcia Marquez, Vargas Llosa, Octavio Paz, Cortazar, Fuentes and others. It’s hard to overestimate the impact of these newly translated stories on North American writers. His stories work with philosophical riddles, questions about chance and doubles, dream landscapes, strange histories, etc. He’s considered a precursor to the school of magic realism. Labyrinths is a must-read.

Here’s a piece of the note I wrote about his early collection, The Garden of Forking Paths, in the post Reading Projects [1] The 1930s:

One snowy night in the early 1970s I sat in the back of a lecture hall in Kalamazoo, Michigan, as, way down in front, the blind, elderly Borges stood beside his handler and took questions shouted down from the peanut gallery. If anyone led with, Señor . . . he’d go, No, just Borges! I still can’t believe I was there.

Bly: I was never impressed with the men yelling around the fire stuff, but his early books, the short lyric poems, worked on me like Haines’s.

Eliade: The summer of 1971 (or ‘72) I tagged along when a friend had a conference with Eliade, but he was old and frail, and I know my friend was disappointed. I’d read several of Eliade’s works by then (part of the religious studies I mention in the following note).

For a time, in my twenties, I was fascinated by myth and ritual, the idea that ritual embodies myth, that “the sacred” could suddenly interrupt ordinary space and time. Later, my fundamentally materialist view of the universe distanced me from thinkers like Eliade.

Buddha: I’m letting this book represent the books on Buddhism, meditation, and Eastern thought. I studied comparative religion when I was young—it seemed important at the time, a way of getting a look at the bigger world—[a major text was Huston Smith’s The Religions of Man (1958)].

This study was totally removed from my own belief system . . . except, perhaps, demonstrat-ing the silliness of adhering to any narrow sectarian doctrine. Somewhere in adulthood I realized I was an atheist, though I didn’t bother with the word until I became radically anti-religion in late life. At some point I also realized that though I was raised in the Judeo-Christian tradition, the basic tenets of Buddhism corresponded to my own observations about life and death; I came to see Buddhism not as a religion, but as a tool to understand the nature of mind and body.

Hemingway: I’m not here to debate the guy’s psyche or attitudes or life choices, but damn he was a great story writer, a re-inventor of the form. There was a sharp generational break between Hemingway’s cohort and its elders—the decade between 1910 and 1920 was complex, violent, confusing, disruptive. It’s good to remember the profound changes in music and painting happening at the same time [Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring premiered in 1913, Duchamps’ Nude Descending a Staircase was shown in the game-changing Armory Show of 1913].

The simplicity of Hemingway’s prose was a conscious purging of all he considered fussy and overblown about the Victorian sensibility. Ford Maddox Ford once said that each of Hemingway’s words were like “pebbles fetched fresh from a brook.” Open his books anywhere and you find classic Hemingway sentences:

The water from the spring was cold and fresh in the tin pail and the chocolate

was not quite bitter but was hard and crunched as they chewed it.

Cowley: Also Hemingway’s memoir of that time and place, A Moveable Feast ( 1964), and Sylvia Beach’s, Shakespeare and Company (1959) [she owned the bookshop of that name in Paris, a hangout for American expats in the ‘20s, and was the first to publish Joyce’s Ulysses].

Faulkner: I put off reading Faulkner for a long time—must’ve heard he was “hard”; a better explanation is that my reading mind had to develop until I was ready for him. He was an odd mix of old and new, tradition and innovation, Southern history with all its contradictions, and modernism with its experiments in form and voice. You see his modernist sensibility in The Sound and the Fury (1929) —stream of consciousness, four sections of text cohering obliquely. It’s often taken to be the apex of Faulkner’s art. It’s a book like, for instance, The English Patient, and, more recently, Cynan Jones’s, Stillicide, that’s considerably less confusing on a second reading.

But As I Lay Dying is by far my fave. A rotating cast of speakers, Bundren family members and a few others, narrating a tale of heroic ineptitude: Anse Bundren, paterfamilias and world-class cheapskate, his three boys and one just-pregnant daughter attempting to honor his deceased wife’s one simple desire—to be buried with her own people on the other side of the river . . . which, wouldn’t you know it, happens to be running at flood stage.

If you’ve never read it, do.

[P.S.: Without Faulkner, no Cormac McCarthy.]

Great list, with many of my own formative books on here (esp. Updike and Carver). When it comes to Brautigan, I first read him when I was a lad of 12-ish and I procured a copy of "Willard and His Bowling Trophy" from the Teton County Library in Jackson, WY, where I was an active cardholder. I distinctly remember sitting in my bedroom alone reading about a young couple having passionate, Brautigan-y sex while watching "The Tonight Show." I never looked at a girl, or Johnny Carson, in the same way again.

Speaking of Brautigan, you should know that while it wasn't a complete reading of "Trout Fishing," the Livingston, MT bookstore Elk River Books did stage a theatrical production of the novel several years ago; I was there in the audience and wrote a few notes: https://davidabramsbooks.blogspot.com/2014/09/trout-fishing-in-livingston-staging.html

If you ever do the Trout Fishing read-aloud event, count me in. We have a number of foundational books in common, especially the Borges, all Munro stories but especially her first collection and "Runaway," and Anne Tyler, although for me it was "The Accidental Tourist" that taught me how to write a certain kind of novel (the kind I wanted to read).