Last week, Substack Central sent a communiqué suggesting we could re-post older pieces so as to lessen the burden of having to come up with new content constantly.

Myself, I favor coming up with new stuff constantly (the logic: moving water takes longer to freeze). On the other hand, you want newer subscribers/followers to get a good grip on what your Substack’s about.

I’ve done almost no re-posting, but I sometimes update earlier lists. Example:

I’ll keep doing that.

When I fired up David’s Lists 2.0 (Spring 2023), the first several posts were poached from my essay, “Oblivion.” Today I’m re-posting them, but in one condensed chunk.

Thanks for having a look.

[Reminder: Please try to read at the Substack site, not directly from email.]

1.

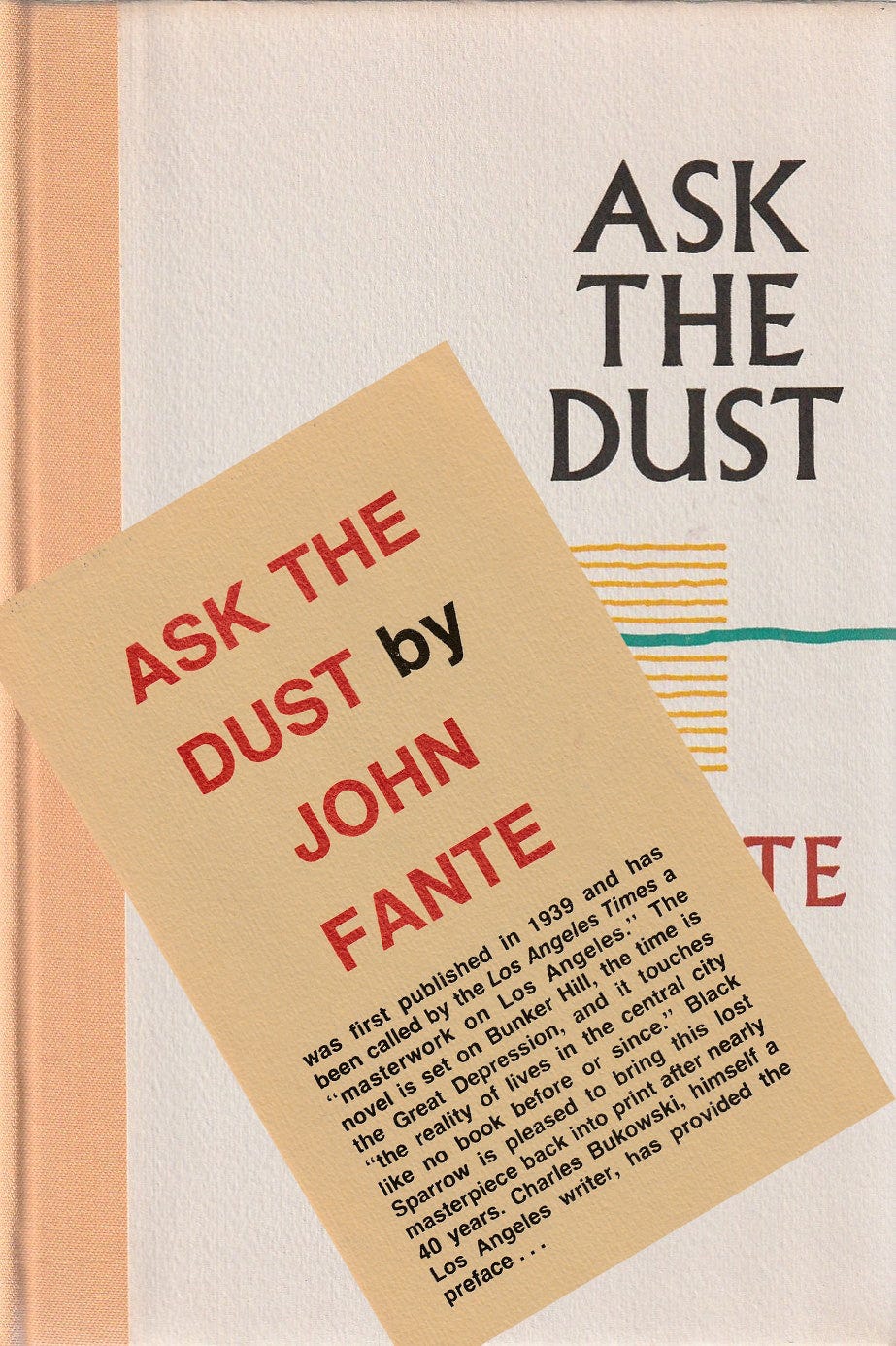

About the time I turned fifty, I challenged myself to read a book published in each decade. On a yellow tablet, I put: 1990s, 1980s, 1970s, and so on (back to the Epic of Gilgamesh, I joked). At coffee one morning, a guy asked if I’d ever read John Fante. Never heard of him, I said. He loaned me his Black Sparrow edition of Ask the Dust (1939). I read it, entered title and author on the yellow pad. Then I read Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Alan Sillitoe (1958); All the King’s Men, Robert Penn Warren, (1946); Hopscotch, Julio Cortazar (1966); Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf (1925); New Grub Street, George Gissing (1891). All was copacetic. I read House of Mirth, Edith Wharton (1905); Fathers and Sons Ivan Turgenev (1862)1.

The trouble started with Cold Comfort Farm, Stella Gibbons (1932). I already had the 1930s; I cribbed “Gibbons” in next to “Fante” anyway. Pretty soon they had company: Down and Out in Paris and London, George Orwell (1933)2; They Shoot Horses, Don‘t They? Horace McCoy (1935); BUtterfield 8, John O’Hara (1935); Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston (1937); Murphy, Samuel Beckett (1938); The Big Sleep, Raymond Chandler (1939); At Swim-Two-Birds, Flann O’Brien (1939).

The yellow pad was an unholy mess.

OK, skipping ahead: The original project finally morphed into Reading Back in Time (aka David’s Insane Reading Project):

Read (at least) one book of prose literature published in each year.

I’d started keeping track of the books I read in 1979 (page of yellow tablet push-pinned to the wall, later collected in a binder). I entered all that into a Word file, along with others I remembered reading pre-1979. Organized by year of first publication, newest to oldest.

I made three ground rules:

I could read them in any order;

There was no deadline (aside from the Big Deadline)

I couldn’t skip a book I knew I should read just because I’d already filled in that year.

Thus, I conned myself into reading Pride and Prejudice (1813), The Count of Monte Cristo (1844-45), Vanity Fair (1848), Our Mutual Friend (1865), Les Misérables (1862), Middlemarch (1871-72), War and Peace (1869), et al, most of which I liked immensely. I discovered Zola’s twenty-novel cycle, Les Rougon-Macquart (1871-1893); The Country of the Pointed Firs, Sarah Orne Jewett (1896); Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs (1861); Moll Flanders, Daniel Defoe (1722).

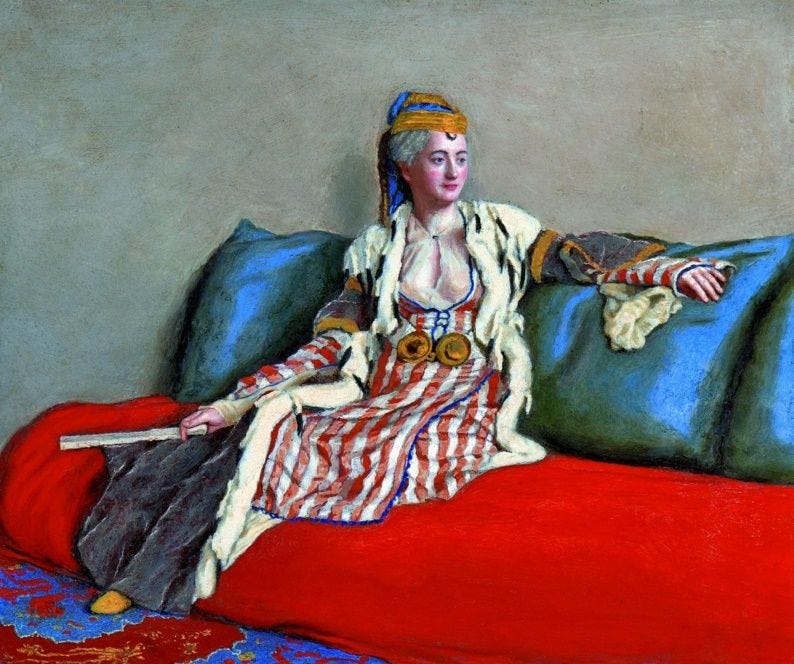

And there were other discoveries: I found that James Fenimore Cooper could be read with unfeigned pleasure (besides The Last of the Mohicans (1826), I read his Revolutionary War espionage novel, The Spy (1821).3 Ditto, amazingly, Sir Walter Scott. On the treadmill one morning, I read Thomas Paine’s anti-religion screed, The Age of Reason (1807) and my inner atheist almost whooped aloud. I read Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796) by Mary Wollstonecraft, better known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)—and for dying soon after giving birth to the future Mary Shelley.4 I read The Turkish Embassy Letters, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1763), writer, wit, wife of England’s ambassador—beyond her literary claim to fame, she’s remembered for introducing the Ottoman practice of inoculation against smallpox into Britain. I read the first volume of The Memoirs of Harriette Wilson, Written By Herself (1825), which begins: "I shall not say how and why I became, at the age of fifteen, the mistress of the Earl of Craven" (but fear not, gentle reader, she has plenty of other stuff to say).

Then a pair of eye-opening memoirs: Mungo Park’s, Travels into the Interior of Africa (1799) and Tent Life in Siberia (1870)5 by George Kennan (shirttail ancestor of Cold War diplomat George F. Kennan). The first attempt to lay a telegraph cable across the Atlantic having failed, the American Telegraph Company hatched a scheme to string wire from the Bering Straits across Siberia to Europe; Kennan and his team spent a couple of years plotting the route, securing timber, enduring insanely challenging conditions, but (the book’s triumph) he details as well their interactions with native, often nomadic, populations. A fascinating read. (Word eventually reached them that a second try at the Atlantic cable had succeeded; the whole Siberia project collapsed, virtually overnight.)

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

2. The Non-Classics

When I was younger, I mostly read contemporary novels/story collections; I read as far back as the Hemingway, Faulkner era. I was scornful of the unhip, uncool, out of date. But deeper into my writing/reading life, I gradually jettisoned my reluctance to dig into what I once considered all that old shit. Age can do that to a guy. At the same time I found myself keener on history itself, recent and not-at-all-recent.6 Anyway, I worked my way through the classics I mentioned above, and a bunch of others. Some went directly into my personal Hall of Fame: Ethan Frome (1911), Portrait of a Lady (1881), Jane Eyre (1847), Tristram Shandy (1760-66).

But there were also non-classics.

When I didn’t have an obvious choice for a year, I usually started at Wikipedia—for example:

I’d vet some titles and pick one. Later on, I came to see that many books had escaped Wiki’s sieve, and added other search strategies.

But “non-classics” is a very baggy term. Let’s drill it down a little:

All of Jane Austen’s books are read today—ditto for the Brontë sisters, and a handful of others. But we often remember even prolific writers for a single work. Sometimes it’s because one book really is head and shoulders above the others. I think of Nevil Shute, a popular/journeyman writer who published two dozen novels—Requiem for a Wren7 and A Town Like Alice are good reads; On the Beach is a great book. More commonly this happens because the Public Memory can hold only so many older books on its shelf. Even relatively modern writers are subject to this fierce winnowing: For most readers, Joseph Heller equals Catch-22. But the fierce, darkly comic Something Happened should not go unread.

Some writers, widely appreciated in their own day, are known only by scholars now, or focused reading groups.8 Which meant, in my case, that I’d never heard of Elizabeth Gaskell [North and South, Wives and Daughters, Cranford] or Maria Edgeworth [Castle Rackrent, Ennui] or George Gissing [The Odd Women, New Grub Street], or Wilkie Collins [The Moonstone, The Woman in White], among a slew of others.

But, finally, moseying through lists of what was published in a given year turned up titles I’d never have crossed paths with otherwise.

A few of those:

Father and Son [memoir], Edmund Gosse (1907)

Red Pottage, Mary Cholmondeley (1899)

A Child of the Jago, Arthur Morrison (1896)

Trilby, George du Maurier (1894)

The Diary of a Nobody, George and Weedon Grossmith (1892)

Anne, Constance Fenimore Woolson (1882)

Erewhon, Samuel Butler (1872)

The Morgesons, Elizabeth Stoddard (1862)

Ruth Hall, Fanny Fern (1854)

Lady of the Camillias, Alexandre Dumas, fils (1848)

The Half Sisters, Geraldine Jewsbury (1848)

Sheppard Lee: Written by Himself, Robert Bird Montgomery (1836)

Domestic Manners of the Americans [reportage/memoir], Fanny Trollope (1832)

Hope Leslie, Catherine Maria Sedgewick (1827)

The Confessions of William-Henry Ireland [memoir] (1805)

Adeline Mowbray, Amelia Opie (1804)9

A Voyage Around My Room, Xavier de Maistre (1794)

Charlotte Temple, Susanna Haswell Rowson (1791)

Granted, these are not all world-beaters. But do they deserve the oubliette? They do not. Why not try one?

3. Going, going, gone

For my 1806 book, I read The Castle of Berry Pomeroy, a Gothic potboiler (attributed to Edward Montague, likely a pseudonym). Besides the full catalog of Gothic horrors—evil sister, nefarious priest with secret past, poisonings and beheadings, characters lost at sea, confined to dungeons, buried alive, plus oodles of backstory, miraculous returns from the dead, reunited lovers, etc.—The Castle of Berry Pomeroy has the distinction of completing the years of the 19th century on my Reading Back In Time chart.

You can download an e-copy to your Kindle for $4.99 thanks to Valancourt Books, a small Virginia press dedicated to “the rediscovery of rare, neglected, and out-of-print fiction.”10

When Valancourt resurrected The Castle of Berry Pomeroy, only two copies were known to exist. One turned up amid a trove known as the Corvey Collection, 72,000-some volumes assembled at Corvey Castle by a German nobleman, Victor Amadeus, between the 1790s and his death in 1834. This library has proved to be one of the foremost collections of British popular fiction of the period, anywhere. Many of the works are rare, some unique. But until the 1970s, the collection remained largely unknown; only since the 1990s has the massive task of cataloging, microfilming, digitizing, and indexing the works begun to make them available to scholars.

If The Castle of Berry Pomeroy was down to two copies, I can’t help but wonder about novels down to no copies. Should we mourn the loss of books we’ve never heard of? Gothic romances? Plenty have survived, including the “seven horrid novels” recommended to Catherine Morland, the heroine of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Valancourt has recently re-issued them as a set, with new introductions. After Austen’s death in 1818, they were so little remembered that until new research in the 1920s it was thought Austen had invented the titles.11

Is it important to have these novels? Or, to ask it differently: Is it sufficient to have only the major, canonical works of the time? Can horror be canonical? What about Dracula and Frankenstein? Necessary? What about Poe? How would we feel about Stephen King’s books vanishing? Or the pulp fiction of the 1930s and 40s? What about comic books and graphic novels?

The past yields to the present is the world’s operating principle. Despite this, some artifacts survive, some works of the imagination are remembered. It’s consoling to believe a collective wisdom informs this winnowing, that it’s each era’s cream that’s preserved. Yet we all know how fraught with cultural bias and accident the process is.12

Now and then, I’ll stop at a shelf of old books in an antique mall, jacketless hardcovers from the first half of the last century. Amid the Zane Greys and Pearl S. Bucks and the names I don’t recognize, are a few that ring a bell, faintly—Warwick Deeping, Louis Bromfield, Ruth Suckow, Henry Bellamann, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Harriette Arnow. Sometimes I take a book down—I like the look of the old typefaces, the smell of the paper, and I like that they’re older than me, yet overlap the heydays of my parents and grandparents.13 Once in a while, I buy one; more often I just move on, a touch melancholy, perhaps, quietly conflicted. How should I feel about old books? How should I feel about the prospect of my books winding up here?

Or not even here?

4. The ending of the essay, “Oblivion”

A New Yorker cartoon: Anguished-looking guy stretched out on the floor beside his typing table. “Help,” he’s saying, “I’ve fallen into obscurity and I can’t get up.” Writers everywhere nod ruefully. Yup, yup. When we were young, we were desperate, crazed, to get into print. What if the world never hears from us?? Later on, it’s, Wow, out of print—boy, that sure went by fast! Later still . . . well, it’s no longer our problem. But at least our books will still be around, right? On shelves, in the ether? They’ll have readers, won’t they?

Won’t they?

Turgenev: As you might guess, a story about a generation gap. I remember being amazed at how au courant it felt—could’ve been the Nineteen Sixties—same issues, same conflicting urges.

Orwell: Orwell probably didn’t invent this form of journalism, but he’s a great early example of what became known, in the 1960s, as New Journalism (aka Participatory Journalism). Back of house Parisian restaurant life [where I first read the term plongeur (pearl-diver—i.e., dishwasher)], then coal mining in northern England. Could be my favorite Orwell nonfiction.

The Spy: I’d later learn it was (loosely) based on Enoch Crosby, one of my wife’s real-life forebears.

Mary Wollstonecraft: Despite the ardor of her feminism, her attitude of class privilege permeates the book—obvious to our eyes, but not hers.

Tent Life: I’ve recommended this book often. Lucid, personal, detail-rich. Try it.

Not-recent: One of the first of these was Barbara Tuchman’s, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (1978). Many years ago my father-in-law remarked (anachronistically) that she’d documented every roll of toilet paper.

Requiem For a Wren: Wrens were women in Britain’s air corps. When the novel appeared in the States, it was titled The Breaking Wave for fear Americans wouldn’t get the reference.

Focused reading groups: For the last several years, I’ve participated in an annual madness called Victober [check it out on YouTube where a bunch of its spokeswomen post their encouragements]. In a past footnote, I think I called these Victober-istas “a pack of daffy English ladies” . . . but I meant that in the best possible way. Also, this was before I’d become a dues-paying, bi-weekly Zoom-attending member of the Trollope Society. [Shakes head.] My younger self would blanch.

Opie: Some of you are probably tired of this story, but, anyway, Opie’s husband was a portrait painter, John Opie. If you’ve ever seen a picture of Mary Wollstonecraft, it’s likely his. But, he also painted his wife when they were newly married. She glows.

[Just discovered the portrait has its own Wiki page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portrait_of_Amelia_Opie.]

Valancourt: Their catalog includes literary fiction by recognizable names (Isabel Colgate, Michael Frayn, Christopher Priest, J. B. Priestly, James Purdy, Nevil Shute, Keith Waterhouse), but its principal mission is re-issuing horror/Gothic/fantasy, LGBT-themed works, Victoriana, plus a category called “vintage thrills and chills.”

Seven Horrid: For the record, they are: The Castle of Wolfenbach, Eliza Parsons (1793); The Necromancer, Lawrence Flammenberg (1794); Horrid Mysteries, Carl Grosse (1796); The Mysterious Warning, Eliza Parsons (1796); Clermont, Regina Maria Roche (1798); The Midnight Bell, Francis Lathom (1798); Orphan of the Rhine, Eleanor Sleath (1798).

The past yields to the present: It was an essay by historian Daniel Boorstin, “A Wrestler with the Angel” [in Hidden History (1987)], that got me thinking about the vagaries of preservation/obliteration. Boorstin cites what he calls The Law of the Survival of the Unread: texts from centuries ago are often official documents or books of high intrinsic value that were infrequently handled. Therefore, it’s easy to find “heavy tomes of Puritan theology,” he says, whereas the New England Primer, of which over 3 million copies were printed, is quite scarce. We might, as a consequence, misread the degree of piety of a place and time.

Amid the Zane Grey’s: Or sometimes it’s a batch of Signet pulps. They were generally reprints and though luridly covered, their slogan was: “Good Reading for the Millions”; easily a third were first-rate novels—Faulkner, Mailer, Dreiser, Mann, Nabokov, Dylan Thomas, Robert Penn Warren, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Nevil Shute, Arthur Koestler, etc. It was among the Signets I found Maritta Wolff, Night Shift (1942); Ann Petry, The Street (1946), William Fisher, The Waiters (1953); Theodora Keogh, The Fascinator (1954).

I first read Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason (1807) long, long ago and was so very grateful to find him. I think I read it even before his best-known book that no one seems to read anymore.

That’s quite a challenge you set for yourself!