New subscribers/followers: Thanks for coming aboard. I promise not to waste your time.

Old subscribers/followers: Thanks for your loyalty and feedback. In lieu of a fee, you give me a massive gift: the feeling that what I’ve learned in my life as a reader is of value to you.

1. NANCY PEARL1:

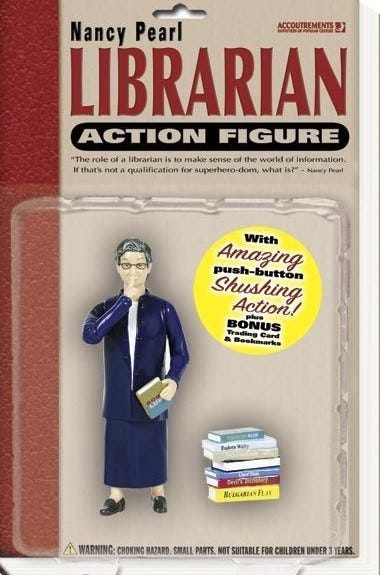

If you’re a reader in these parts, you know the name—from her Book Lust series maybe, or you heard her talking up titles on Seattle’s KUOW (or elsewhere), maybe you even have one of the Nancy Pearl action figures.2

Or maybe you know Nancy Pearl’s Rule of 50, having to do with: a) the number of books in the world, and b) the number of years in you:

If you’re fifty years old or younger, give every book about fifty pages before you decide to commit yourself to reading it, or give up. If you’re over fifty, subtract your age from 100.3

2. SYNCING:

Today’s post isn’t really a list of books I didn’t finish . . . it’s about why we abandon a work we’ve begun reading. [Beyond, meh.]

Let’s start here:

You and Book X form a relationship. Could be a blind date, but most often friends/reviewers/book bloggers have already influenced you. So what’s your mood going into the meet-up? Wait-and-see? If so, are you closer to the open-minded but waiting to be convinced end or the ready to hop on the bandwagon end?

Or what if you’re not in wait-and-see mode—you want to be, but you hardly slept last night, your mind’s a pit of sludge . . . or you can’t stop trying to parse that thing your beloved said the other night . . . or (refusing to squander time!) you’re in the car waiting for your daughter after swim practice but every ninety seconds you eyeball the double doors again . . .

Picture the board in a recording studio4: columns of sliders and dials that enable youn to collect, layer, and fine-tune strands of sound. And let’s say you’re in the control room hearing a mix. Whaddya think? someone asks.

How do you answer?

If we’re talking about making a record, it depends on:

Why you’re there, what your role is—are you the artist’s girlfriend/boyfriend/long-suffering spouse or manager or the sound engineer or the producer or the marketing person or another musician who stopped by . . .

What you expected to hear vis-à-vis what you actually hear . . .

Your level of technical know-how . . .

Your history with the artist . . .

Your mood/frame of mind . . .

Though we seldom think of it this way, the same is true of reading a book. The experience depends on how well you and the book are synced.

3. SYNCING TROUBLES FROM MY READING LIFE:

Bad writing:

You start reading. As you take in the opening particulars (what’s going on, who’s talking, when is this?), another sensor’s asking: Am I onboard, am I having fun, do I feel like this writing’s going to tell me stuff I don’t already know?

A remark of Sting’s I heard the other day: If nothing surprises me in the first eight seconds, I move on.

Harsh?

OK, but don’t we know, early on, how smart the writing is, whether it’s going to be too same-old-same-old, or too timid, too self-satisfied, too AI-ish?

In my first post-vacation post last September I talked about Rain Girl, by Austrian Gabi Kreslehner. I subjected you to a taste of its prose, but I don’t have the heart to re-quote it here.5

Anyway, “bad writing” is an easy call—shooting fish in a barrel.

Breaking trust with readers . . .

On page 5 of Robert James Waller’s, The Bridges of Madison County, you find this paragraph:

No, he couldn’t. The paper mill is upwind from Missoula, 117 miles to the south.

I hear you say: But it’s fiction—you’re supposed to make stuff up. We’ll get back to that in a second.

Ever hear the story of Van Halen and the brown M & Ms? In their multi-page contract the band stipulated there had to be M & Ms backstage, but absolutely no brown ones. Prima-donna rock star bullshit, right? Actually, no. If the band found brown M & Ms backstage, it meant the venue hadn’t paid close attention to the specs within the contract, and therefore couldn’t be trusted to get the other things right . . . which could be a matter of life and death for the crew.

That’s how I felt about Waller—he was sloppy, made an unforced error, and this disinclined me to believe the rest of what he said. This is a small example but illuminates a fundamental issue: Don’t be sloppy/lazy/inattentive. Do the work, honor your contract with the reader.6

Writerly self-indulgence:

We were crisscrossing Montana on a bus, putting on a dog-and-pony for teachers [I represented Montana’s Writers-in-the-Schools Program]. I’d been reading a Tom Robbins novel, Perfume Jitterbug (1984)—some years earlier I’d logged Another Roadside Attraction (1971) and Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (1976), and been caught up in his whimsy and inventiveness and counter-cultural vibe. But when we got off the bus in Lewistown, I just . . . dropped the book in a trash can. Popular as Robbins was (bestseller-popular), it had hit me that he was just fucking around; the story wasn’t serious. Wait, though . . . isn’t fucking around essential in art-making, aren’t shots in the dark and serendipity and flights of fancy what let art transcend the expected, the ordinary? Yes, absolutely! Except, sometimes—all at once, maybe—you realize you’re tired of the whipped cream and want the fruit.7

I’d read Pynchon right after college—V. (1963) and The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) and Gravity’s Rainbow (1973). I hadn’t kept up with his writing, but maybe fifteen years ago I dove into the 1085-page Against the Day (2006). Wow, I thought, so many story lines, so much stuff going on—it was going to be so cool when he ultimately uncovered the thing at the center, what all the disparate story matter was tied to (or emanated from) . . . I mean, this was Pynchon, a master. Except, uh oh, no reveal! No there there. All those pages, he’d simply been amusing himself [I was reminded of the last few seasons of Lost]. Thus, as to Pynchon (in the words of my esteemed mother when she’d had enough) over and out.

Now: Neal Stephenson. I included his 2021 novel, Termination Shock in last year’s post on cli-fi, and said I’d liked Snow Crash (1992) and Cryptonomicon (1999), and was a big fan of Seveneves (2015)—read it twice, in fact. That said, partway through Quicksilver (2003), first volume of The Baroque Cycle8, I bailed. The stuff was richly inventive—also rich in ideas/science. His critics often carp about the cargo of scientific exposition in his work [aka, the info dump], but that never fazed me. Rather, Quicksilver had stopped seeming serious to me.

Except, again, “seriousness” is tricky. As we know, turgid/humorless/deathly serious novels are NO FUN AT ALL.9 But seriousness shouldn’t feel ponderous/leaden/airless—regardless of subject. Regardless of subject, good writing is buoyant.

Maybe it so happens that you love The Baroque Cycle. More power to thee. [Another aspect of the novels in today’s post: many have legions of fans.]

Chacun son goût.

Too early, too late:

I tried Ulysses when I was too young, bounced off it, twice. I didn’t yet know how to tackle a hard book, how to get help from secondary sources, how to persist, how to enjoy it, how to handle its complexity. Ditto, Justine, first book of The Alexandria Quartet. Maybe you, too, have books on your shelf with bookmarks showing how far into the caverns you got before turning around?10

In the course of prepping Birth Year Project posts, I’ve tried reading a few works I knew I wasn’t the target audience for, yet thought I should check out on general principles, including, last year, Anne of Green Gables (Lucy Maud Montgomery, 1908) and Madeline L’Engle’s semi-autobiographical novel, The Small Rain (1945).

I read against the grain semi-often—from Ann Bannon’s Beebo Brinker novels (classic lesbian pulps of the late 50s/early 60s), to Ann Radcliffe’s gothic melodrama, The Italian (1797) to Le Petit Prince . . . The Chronicles of Narnia . . . William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation . . . The Letters of Pliny the Younger—because sometimes I read the way I’d visit a museum in a foreign city. But it didn’t work with L’Engle and Montgomery. I came to them too late, and was unable to sync my jaded septuagen-arian reading brain to their storytelling voices.

Ickiness [1]

Novels are about change: “the ordinary/the usual” broken into by “the not-normal/the one-of-a-kind.” This is how drama works—lacking it, an artifact is inert.

Any change disturbs the water, even a windfall or a new love or a reprieve. You can’t be a novelist without an in-the-gut appreciation for this dynamic. So what we’re really talking about is writing that exceeds (by a lot) a baseline of drama, that imagines life toward the in extremis end of the scale where lie pain, despair, cruelty, injustice, violation/ transgression/humiliation, collapse, gore.

Ickiness is visceral—and hugely subjective. If some people didn’t eat it up, we’d have no horror flicks, horror novels. That stuff is meant to terrify you/gross you out—if it doesn’t, you want a refund.

I’m too squeamish for most of it myself. Much as I admire Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley, I have no desire to freshen the image of the alien already lodged in what my wife calls her brain pan.

But I do like intensity, stories where big things are at stake. As my long-ago mentor, Bill Kittredge used to say, You have to take the trouble out and waltz it around the dance floor.

Once in a while, that trouble gets real bad. Here are three short, tough reads, novels that require a strong stomach, but ones I champion even so:

Mr. Pip, Lloyd Jones (2006) [New Zealand]

This Blinding Absence of Light, Tahar Ben Jelloun (2001) [Morocco]

Woman at Point Zero, Nawal El Saadawi (1977) [Egypt]

The word gratuitous often pops into this discussion. Is the violence (or sex) mandatory? Do we have to see it? [I’ll get to this below.] Does the actress really need to take her shirt off? Do we really need to watch the head explode?

Here are a couple of novels I pulled the plug on due to ickiness:

Marabou Stork Nightmares, Irvine Welsh (1995).11

How High We Go in the Dark, Sequoia Nagamatsu (2022) 12

And several named by Reddit posters:

Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke, Eric LaRocca (2021)

Tender is the Flesh, Agustina Bazterrica (2017)

Haunted, Chuck Palahniuk (2005)

The Rape of Nanking (nonfiction), Iris Chang (1991)

Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy (1985)13

Most likely, you have your own list of these. Below, I’ll say a few words about being the wrong audience for a book—and maybe that’s a better way to think about this. You’re the casting director auditioning novels for the role of What To Read Next. The waiting area is chockablock with applicants; one by one, you sample their talents, tell most, Sorry, not this time —

Ickiness [2]

Questions for writers of gruesome material (leaving aside horror writers):

What do you show?

What do you imply?

What do you skip altogether?

It’s strictly case-by-case. It depends.

If I was writing a sex scene, I realized at some point, it had to do something else.14 If it’s just sex, cut to the morning, coffee, the smile in the corner of the mouth.

In a craft talk, a colleague once said: When the action’s hot, write cool. Terrific advice. Follow it and you avoid over-amping the prose, marking yourself as a rookie. The big dramatic spots in a story are often handled best with deliberate restraint, even deadpan. In Norman Mailer’s first novel, The Naked and Dead [1948],15 American soldiers struggle to take a mountainous, densely jungled island in the Philippines; what began as an exercise of grit, flinty perseverance, gradually becomes a tale of futility, misjudgment, pointless sacrifice. Two of its major plot points are given in utterly flat sentences:

A half hour later, Lieutenant Hearn was killed by a machinegun bullet which passed through his chest.

And:

In the excitement, everyone forgot about recon.

Greek dramatists (Aeschylus, in particular) were hardly shy about depicting big emotions, but acts of violence took place offstage. Here’s a piece that discusses this question in more detail:

https://theconversation.com/how-far-should-we-go-when-depicting-violence-55560

Yaaawn—

Whether in Chapter One, or deeper in, you realize you’re bored, having no fun, learning nothing . . . or that your mind’s nimbler than the writer’s and you’re going, C’mon! Pick up the pace . . . or you’ve lost all hope that the writer will surprise you . . . or the prose, word choice, is so bland/meek/namby-pamby, Chamber-of-Commerce-ish that you’re doing the Bob.

This one’s pretty easy, too. See The Rule of Fifty.

Does it really matter who gets the blame for this non-syncing, you or the material? If you think it’s you, you might believe the book’s worth a second shot (optimist!) and you keep it around awhile.

I’m always scratching about for writers of the recent past I haven’t read, which led me to Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time (12 vol., 1951-1975) a shot. Despite his big reputation (there’s an Anthony Powell Society!), I Could Not Stay Awake.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Dance_to_the_Music_of_Time16

Steig Larsson had written three of ten Lisbeth Salander novels [aka The Millenium Series] when he died suddenly. The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo was published (posthumously) in 2005, then the two others: The Girl Who Played With Fire (2006) and The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest (2007). In 2013, Swedish journalist David Lagercrantz was hired to continue the series; The Girl in the Spider Web was published in 2015.

The pleasure I’d gotten from the Dragon Tattoo novels derived from Salander’s character (the chilly ambience, the transgressiveness, etc.)—not the writing, which was serviceable at best. I started into Lagercrantz’s first offering with a mild hope, but by fewer than fifty pages it had evaporated. The prose was lazy, dull; I just . . . quit reading.

Henry David Thoreau’s older brother John died (of tetanus) in 1842, aged 27. Three years earlier the two brothers took a canoe trip Thoreau later documented as A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849). Imagine my heavy heart when I saw that the work was almost entirely free of reflections on the lost brother. In their place, dry philosophical digression. I grew up 26.7 miles from Walden Pond; my copy of Walden (1854) is full of ink and highlighting; I consider it a major player in my understanding of 19th C. New England. Cape Cod (1865) is good reading, too. But, friends, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers was uphill sledding, on gravel.

Ditto, Boswell’s The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (1785). What did I expect—pub chat, Highland/Island landscape, a window into that slipping-away place and time? Could Not Keep My Eyes Open (cf. philosophical digression, above).

It’s not you, it’s me [1]:

You’re not the right reader for this book. Sure, you can read it, examine it as an artifact, but it’s not of your books. I wish this idea had more traction among book raters at Amazon (or wherever).

Say you’re a eighth-grader and happen to pick up Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled or David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress or Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport or The House of Leaves or Thus Spake Zarathustra or Crime and Punishment . . . or Borges, Beckett, Lessing, Fuentes, Calvino . . . You’re probably not going to post a scathing review online (though we’ve all seen some that say, I had to read this for a class and I thought it sucked . . . or I just don’t see how this could’ve won that big prize—our book group read it and not one of us liked it!!!).

Here’s the trouble: We’re all entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but that doesn’t mean we all get happiness; we have rights equally (you know, in theory), but we’re not equal in life experience, training, brain power, disposition, stamina, etc. Which means, there are times a reader ought to sit tight until the urge to lambaste wanes, to leave the job to readers better-suited to judge that particular work.

What an un-American thought!

Or consider being the writer, watching the one-star reviews dilute the many raves, the well-written/insightful remarks by sharp readers . . . which tell the algorithm the book’s a C+, possibly a B-. 17

It’s not you, it’s me [2]:

That book was so cool . . . you once thought.

But now you don’t. For years I talked up Cannery Row [John Steinbeck (1945)] and The Colossus of Maroussi [Henry Miller (1941)]. In the late 90s, I re-read both—or tried to before throwing in the towel. Strange, I’d been so keen on them in my early twenties. Except, of course, that was the thing—I wasn’t in my early twenties now. I’d read hundreds of books since then. I was no longer the kid on the stairs, peeking into the room where the grownups were having their party . . .

It’s sweet when a re-read deepens our appreciation for books we remember championing, or when we realize our reading savvy has caught up with a hard book’s intelligence or artistry. If the re-read’s a letdown, it’s tempting to poor mouth our younger selves. What a Rube I was! How could I possibly have believed this book was . . . original? stunningly wise? wickedly funny?

It’s tempting, but isn’t it better to take a breath, give one of those wistful shrugs, and take it instead as a symptom of our growth?

Two further questions, left hanging, for now:

What if you read a book all the way through, liking it, but don’t remember it afterward? Was the experience a waste?

What lessons ought writers extrapolate from the ideas in today’s post?

I welcome your thoughts.

[Full disclosure: there was actually one more, but, uh . . . maybe it’ll come to me later.]

Nancy Pearl: I have the good fortune to know Nancy.

https://www.nationalbook.org/people/nancy-pearl/

https://seattlechannel.org/BookLust

Rule of Fifty: These days (deep sigh) I need to read but 23 pp.

Sound Board: My younger son’s a program manager at KEXP in Seattle—a major player in indie radio, streamed world-wide. On the side, he has a small recording/mixing studio [https://www.hearmeshimmer.com], and drums in indie bands. Thus, it’s natural that this image comes to mind, but I’ve thought about the sound board/book-writing connection for years [tweaked, also, by re-watching McCartney 3,2,1 on Hulu and YouTube. As producer Rick Rubin chats with McCartney he frequently isolates tracks from Beatle/Wings/McCartney recordings—bass, vocal parts, etc.

Rain Girl: You’re welcome.

Waller: Novelists whose books rely on research must draw a line—or circle? Within it, you’re free to invent; beyond it, you honor fact.

In Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson re-names her hometown (Sandpoint, Idaho) Fingerbone. Ditto Faulkner, Yoknapatawpha County.

Most of my Montana stories take place in Sperry County—not Kalispell where I lived (I borrowed the name from Glacier National Park’s Sperry Glacier). But beyond its boundary, I stuck with the actual names (Missoula, Great Falls, Butte). Many writers make this kind of distinction—it lets them take emotional ownership of the material.

Robbins: Robbins just died; I feel crappy about dissing him. He had scads of fans, after all, and was, regardless, a fellow practitioner of lit . . . so I need to steer us away from ad hominem language. He was not a bad writer and he was not writing bad books; I just wasn’t well-synced with them, though I had been earlier. And this question of “being serious” is a slippery one . . . Some books are un-serious in tone but are sharp in their satire;

Baroque Cycle: The others are The Confusion (2004) and The System of the World (2004)].

NO FUN AT ALL: I wouldn’t read Dreiser’s Sister Carrie again with a gun to my head.

Ulysses/Alexandria: Later I read both, and both, despite the extra work they took, despite having to accept their excesses (or understand how the excesses are integral to their design), both became essential parts of my reading life.

Irvine Welsh: I was in Scotland. Knowing I was a fan of Trainspotting (1993) someone suggested this one. Sometimes I groove on (very) dark humor, a bit of the ew—. All I remember of Marabou is that its ickness made me quit reading.

Nagamatsu: This one is new, effusively reviewed, the kind of dystopian sci-fi I typically go for—in this case a collection of pieces linked by theme. I had high hopes. Including it here seems grossly unfair to Nagamatsu . . . but the fact is I stopped reading it when the ickiness of the imagery hit critical mass (for me). I plan to try this one again.

Blood Meridian: I have a long, complex relationship with McCarthy’s books. I read this one many years ago—it was cringey, yes, but I got through it. Later, after I’d read everything else he’d published, I had much better lens to see it through—it’s not even the darkest thing he wrote. Nonetheless, unlike most of the other books, I’ve never re-read it.

Something else: In my story “Attraction,” Marly finally seduces Charles in the back of his van . . . but (she’s on top) he gives a really good, um, thrust, and her head cracks the dome light, leaving a gash in her scalp that requires a ride to the ER. How humiliating! And yet, somehow, it startles her into knowing she and Charles are bonded, that going to him was the start of the rest of her life.

The Naked and the Dead: During the first years after WWII, novels by participants began to appear—James Jones’s, From Here to Eternity [1951] and others. But Mailer’s was the first.

Anthony Powell: As an Anglophile, I love how the Brits confound us as to the saying of names:

Gloucester = Gloss-turr [unless you’re in Massachusetts where it’s Glah-stuh].

Mary Cholmondeley [Red Pottage, 1899] = Chumley.

Samuel Pepys = Peeps.

St. John = Sin Jin

Marjoribanks = Marchbanks

Anthony Powell = An-tony Pole

C+: My second novel, The Daughters of Simon Lamoreaux (2000), contained a question—what became of the girlfriend?—but wasn’t a genre novel, not “a mystery.” Which didn’t stop some posters from griping that it wasn’t a good mystery novel.

[In an earlier draft of this post, I had the sentence: How tired I am of brilliant novels being dissed by dimwits. But, as you see, I cut it . . . because I don’t want anyone thinking I’m an elitist, an intelligence snob. Too bad, though—I kinda liked it, and now you’ll never get to read it.]

Thanks for this, David. I'm self-publishing my first novel this month and perused with interest the various reasons for people not to read it. Hopefully I've had good enough teachers to where it won't be a problem :), although "writerly self-indulgence" has me a little worried. Then again, isn't all writing a form of self-indulgence?

Hi David,

I loved this post best of all.

And I only have to read 24 pages. Excellent.

xox

Mitzi