New subscribers/followers: Thanks for signing up—I promise not to waste your time!

1.

We’re going to look at two interwoven questions today.

Why do we like watching/reading about crime?

Why do writers “borrow” plots?

Let’s start here:

Stories are strings of verbs. [William Gass]

No matter how spiffy/jaw-dropping/unforgettable our images, they don’t make a story. A “slice of life” is not a story. A “prose poem” is not a “flash fiction.”1

“Something is” isn’t a story. “Something happened” is. The reader goes, “OK, so then what?” That’s where the strings come in. Actions lead/push us forward, actions create change. You’re in your unmarked car, arms cramping from holding the binocs, empty coffee cups and balled-up burrito wrappers for company . . . Jesus, you think, this is just incredibly— but no, wait, wait, there he is, slipping out the alley door . . .

And you’re off.

This, then that. This as a result of that. This triggering the next this. This entering you into the arena of time, of unfolding: beginning, middle, end.

2.

Another comment from William Gass:

We are so pathetically eager for this other life, for the sounds of distant cities and the sea; we long . . . to pit ourselves against some trying wind, to follow the fortunes of a ship hard beset, to face up to murder and fornication, and the somber results of anger and love; oh, yes, to face up—in books . . .2

Gass invokes a gaggle of truths here—about why fiction exists, about the relationship between safety and danger, about art’s concentration. By “concentration” I mean: while some literature is diffuse, haphazard-seeming, fragmentary, writing that grips us tends to not be that way, tends not to be life-like but like a distillate of life—more balsamic reduction than balsamic vinegar.3

3.

Maybe (if you don’t write), you imagine writers rubbing their hands together each morning, going, Hot damn, can’t wait to get started!

And maybe (I’ll entertain the possibility) it’s true for some writers, on some days. More often, working on a piece is what makes you want to work on the piece. Working makes its own gravy. But what if you’re between projects—i.e., there’s no dogfood already in the bowl, waiting for the warm water of your genius? The writer’s existential dilemma: Empty bowl/blank page. How on earth to survive it, to get past it?

Working makes its own gravy.

One time-honored way is to use a template, a model, a known pattern (or you can think of it as an armature or spine that holds your story up). When a work fails to inject fresh life into the template we call it formulaic, predictable, trite. But that’s not the template’s fault. We’ll get back to crime fiction in a moment, but first a quick look at templates/borrowings/sources/reworkings:

As we know, Shakespeare swiped from English/Danish/Roman histories, Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, Samuel Daniel's The Civil Wars between the Two Houses of Lancaster and York, medieval poetry (and anything else not nailed down).

Virgil re-does Homer (as does James Joyce, also Cold Mountain, also O Brother, Where Art Thou?). Chaucer re-does Boccaccio (as does Dan Simmons’ Hyperion sci-fi series and Emily St. John Mandell’s Station Eleven). Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres is King Lear in Iowa, West Side Story is Romeo and Juliet. Damn Yankees is Faust. Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities is The Travels of Marco Polo.

Or a story extends/augments the source: The Wide Sargasso Sea (Jean Rhys, 1966) prefigures Jane Eyre’s madwoman in the attic. Margaret Atwood’s, The Penelopiad (2005), gives the spouse’s angle, as does Ahab’s Wife (Sena Jeter Naslund, 1999). The Other Bennet Sister (Janice Hadlow, 2020) and The Other Boleyn Girl (Phillipa Gregory, 2001), give a sister’s. John Clinch (Finn, 2007) and Percival Everett (James, 2024) give Adventures of Huckleberry Finn through other eyes.

4.

OK, let’s put these ideas together:

facing up to murder and fornication, and the somber results of anger and love . . .

balsamic reduction . . .

dry food in the bowl . . .

template . . .

We find ourselves homing in on both why crime writing is so popular among readers and why writers look to real-world events for spots to anchor their fiction.

But, immediately, a fork in the road: Some writers stick with the known facts, in which case, they’re writing “true crime”—Ann Rule, to name one of this tribe, has fashioned a highly rewarding writing life from this. Names are named, chains of event maintained, outcomes revealed.4 The telling is finessed, details doled out in a scheme that creates suspense; unknowns can be speculated about, alternate theories/interpretations laid out, weighed, but like their TV counterparts—Dateline, 48 Hours, The First 48, et al.—true crime books, ultimately bear allegiance to what happened.

Whereas, fiction writers appropriate the events. They take possession, keep as much or as little as they want; they alter, spin, subvert. In short, what actually happened becomes a starting (or ending) point.5 Sometimes this theft is acknowledged outright: Based on true events, a movie might say (really, this is a marketing decision, to underscore a work’s real-world gravitas). In novels, we’re sometimes given insight about the source in the end-of-book acknowledgments; this seems to be the new protocol—writers of earlier generations seldom wrote such statements. Sometimes—as in the mini-series Inventing Anna (2022)—we get a twee disclaimer/non-disclaimer: This whole story is completely true. Except for the parts that are made up.

There’s lots more to say about appropriation than I have room for today. But much of it is “extra-literary”—that is, not about the artifact as an art work, but about ethical or moral or legal issues surrounding its creation. How much borrowing is too much? Are the depictions of actual people so thinly veiled as to be libelous, actionable? Is a given story yours to write—do you have the right to write it?6 What about spilling family secrets? Writers can find themselves balanced on a knife edge: Wow, what juicy stuff! pitted against If I write this my mother will fall down dead. Is ruthlessness mandatory? Oh, and there’s this: sometimes, borrowing, we lose track of the fact that real people are involved.7

5. Bookers:

This morning’s email brought the (roughly) bi-weekly post from the Booker Prize Foundation’s Substack [thebookerprizes@substack.com]. It’s a good site—groupings and reconsiderations from the rich catalog of Booker winners, and several hundred short- and long-listed works since its startup in 1969,8 also an array of interviews and other features. Smart, well-organized, appealing to the eye. You’ll find titles/authors you’ve read—the likes of Margaret Atwood, A. S. Byatt, Roddy Doyle, Kazuo Ishiguro, Hilary Mantel, Ian McEwen, Salman Rushdie, Zadie Smith, Colm Tóibín, Sarah Waters, and so on. But there are a slew of others—writers from the early years you’ve never heard of or forgotten about, and writers of quirky/non-mainstream/hard-to-pigeonhole works . . . I’ve mentioned James Kelman here, but there’s Anna Burns’, Milkman (2018 winner), Magnus Mills’, The Restraint of Beasts9 (1998 shortlist), Micahel Frayn, Skios (2012 longlist), Lloyd Jones, Mr. Pip (2007 shortlist), Jon McGregor If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things (2002 longlist), and an abundance of others. Highly recommended.

I mention this because, minutes ago, I happened onto two lists that speak to today’s theme:

https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/features/the-best-crime-novels-from-the-booker-library

https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/features/booker-nominated-books-that-reimagine-classic-works-and-ancient

6. Twelve novels from the past 100 years based on real crimes:

The Perfect Nanny, Leïla Slimani (2016)

A Brief History of Seven Killings, Marlon James (2014)

We Need To Talk About Kevin, Lionel Shriver (2003)

Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood (1996)

Black Water, Joyce Carol Oates (1992)

The Executioner’s Song, Norman Mailer (1979)

Ragtime, E.L. Doctorow (1975)10

Looking for Mr. Goodbar, Judith Rossner (1975)

In Cold Blood, Truman Capote (1966)11

The Night of the Hunter, David Grubb (1953)

Double Indemnity, James M. Cain (1943)

An American Tragedy, Theodore Dreiser (1925)12

You’ve likely read at least a few of these. They’re worthy, they keep a tight grip on our attention, they scratch our itch for (vicarious) transgression. But as these are ones you already know, and as the prime directive of this Substack is to suss out the less-familiar, here are a batch of those:

Little Deaths, Emma Flint (2017)13

Nineteen Minutes, Jodie Picoult (2017)14

The Girls, Emma Cline (2016)15

The Missing Word, Concita De Gregorio [trans. by Clarissa Botsford] (2015)16

Burial Rites, Hanna Kent (2013)17

Quiet Dell, Jayne Anne Phillips (2013)18

The Disappearance: A Novel Based on a True Crime, David H. Hanks (2007)19

Fred and Edie, Jill Dawson (2000)20

Slammerkin, Emma Donoghue (2000)21

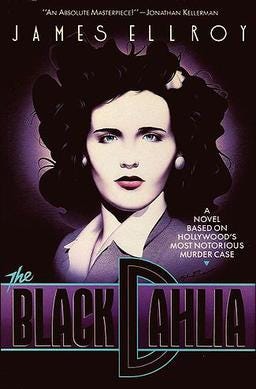

The Black Dahlia, James Ellroy (1987)22

A Pin to See the Peepshow, F. Tennyson Jesse (1934)23

Prose poem: Though some are. My all-time favorite example is “A Story About the Body” by Robert Hass.

The young composer, working that summer at an artist's colony, had watched her for a week. She was Japanese, a painter, almost sixty, and he thought he was in love with her. He loved her work, and her work was like the way she moved her body, used her hands, looked at him directly when she made amused and considered answers to his questions. One night, walking back from a concert, they came to her door and she turned to him and said, "I think you would like to have me. I would like that too, but I must tell you that I have had a double mastectomy," and when he didn't understand, "I've lost both my breasts." The radiance that he had carried around in his belly and chest cavity—like music—withered very quickly, and he made himself look at her when he said, "I'm sorry. I don't think I could." He walked back to his own cabin through the pines, and in the morning he found a small blue bowl on the porch outside his door. It looked to be full of rose petals, but he found when he picked it up that the rose petals were on top; the rest of the bowl—she must have swept them from the corners of her studio—was full of dead bees.

--“A Story About the Body” [from HUMAN WISHES: by Robert Hass (1990)]

Gass: A favorite quote, from Fiction and the Figures of Life (1970), which I hope people still read. A number of my core ideas about fiction arose from that handbook. I’m just realizing I haven’t posted about other handbook/craft books . . . probably should wait for another day, but, quickly, I absorbed a lot of Milan Kundera’s ideas from The Art of the Novel (1986) and Testaments Betrayed (1993).

I’ve never tried Gass's big novels—The Tunnel (1995), for instance—but as a young story writer I bonded with his early collection, In the Heart of the Heart of the Country (1968), and, later, found in his debut novel, Omensetter’s Luck (1966) some of the same strangeness I came to love in Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy.

Here are two more pithy-but-exceedingly-useful lines from Gass that are embedded in my understanding of how/why fiction works:

A character is a bright human image.

In fiction there is no such thing as description, there is only construction.

I’ll save unpacking these for another day.

Distillate: This is a big subject, but quickly: Writers of scenes fall somewhere on the scale between putting everything in and leaving almost everything out. Victorian novelists (I’m on an Anthony Trollope jag) tend to say everything—because maximalism was the fashion, people were vastly less familiar with the look and feel of things beyond their home places, reading fiction was for people with time on their hands, there were fewer distractions, etc. In our time, we have quick short books and more say-it-all books. But we’re used to processing info at a much faster rate than our forebears, we know how things look beyond our own hearths, and we have (despite our world of “labor-saving” devices) crazy-making demands on our time. So, partly about the zeitgeist, partly aesthetic taste.

When I was learning how to write a scene I was influenced, in part, by handbooks about screenwriting. I started by asking what I had to say to put the reader there, what the reader needed to know to make sense of the moment,* what the scene needed to do to push the story forward . . . then I built the scene up until that was achieved (though most writers do it the other way: write a lot and pare it back and back . . . or should).

[*Substack won’t let me footnote a footnote . . . if I could footnote “what you need to make sense of the moment,” I’d tell you that I sometimes call this “the existential reality of the moment,” which, I know, oozes heaviosity . . . but take it at face value: What’s going on? What’s at stake? What’s unique/crucial/pivotal about this story moment?]

Anyway, arc: I realized that every scene consisted of beginning, middle, end, and learned to give as little of “beginning” as I could get away with, and ditto “end,” leaving mostly middle, which was stripped of what didn’t need saying. This is especially true in dialog. Amateurs tend to have the characters shoot the shit back and forth—because it’s realistic. Experienced writers know that realism isn’t the goal—the goal is the illusion of reality, the essence of reality. In other words, a good full-scene in a story isn’t everything that was said back and forth, it’s a distillate.

Balsamic reduction.

True Crime writers: There are loads of these. Here’s a link from a few years ago:

https://the-line-up.com/7-true-crime-books-for-ann-rule-fansThere are many similar lists online.

True crime vs. crime fiction: I’ve made it sound like there’s a clear distinction between these, but the line is often blurrier. In prior posts, I’ve touched on hybrid genres—“New Journalism” and “autofiction” and “nonfiction novel”—an example is below, Norman Mailer’s, Executioner’s Song [1979]. Mailer presented the facts (as known) about Gary Gilmore’s killing of several strangers in Utah, his subsequent capture, trial, and execution by firing squad (the first since the U. S. reinstatement of the death penalty), using the fiction-writer’s tools (therefore, for instance, the dialog is imagined). That book won the Pulitzer for fiction in 1980. (See note on Capote, below).

The right to write: Consider Wallace Stegner’s use of Mary Hallock Foote’s letters when writing his Pulitzer winner, Angle of Repose (1971):

https://www.altaonline.com/books/fiction/a39179237/wallace-stegner-mary-hallock-foote-plagarism/

Consider the hue and cry around William Styron’s writing of The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), which continues to this day:

https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/meditations-confessions-nat-turner

The “who owns the story?” or “who has permission to write about a particular slice of history?” issue still vexes us, partly because our sensitivity to cultural/racial appropriation has become keener (a good thing) and partly because, in our day, we’ve inhaled the fumes of identity politics (not so good a thing, maybe).

In 2023, Debra Magpie Earling published the novel, The Lost Journals of Sacajewea. Debra is Native-American (Bitterroot Salish). What if I’d tried to write that book, a white guy from Massachusetts? OK, a ridiculous example, I grant you. Yet, I did spend nearly four years writing a novel set in Estonia, a place I knew less than nothing about when I began. [Come to think of it, that’s not so hot an example, either, since the manuscript never saw print.] Anyway, this question refuses to go away.

Real people: When I was a young short story writer, I read Syd Field’s handbook on screenwriting [more on this here]. Under its influence, I constructed a story using his method—file cards, three-act structure, major plot turns at the one-quarter and three-quarter marks.

As it happened, a murder trial had been held at our county courthouse, just blocks from our place. I thought: Why not borrow the facts of that case for my plot-design exercise? So I did—kept the basic situation (the general locale, the dynamic that led to an old man’s death), but made the rest up. The story eventually appeared in my first collection, Home Fires (1982). I went on with my writing life—couple more collections, some novels. I barely remembered that early story.

Then, in the 1990s, I ran into a lawyer I knew. He said he’d been called down to the state prison in Deer Lodge to act as counsel for several inmates involved in a riot there. And then he said something like, Oh, and your name came up— I’d always assumed (insofar as I’d thought about it at all) there was zero chance the man convicted of the murder would ever cross paths with my story. An obscure little book from a university press? Nah. As it turned out, my attorney friend explained, the guy knew all about it. My blood went icy—instantly, I pictured myself or my family in the crosshairs. Well, no, he went on, picking up on my distress, he seemed to be proud of it, actually. He’d been written about . . .

Anyway, I’d learned my lesson.

Booker: There have been several name changes/spinoffs/morphings of eligibility rules over the years, but that doesn’t need detailing here.

Magnus Mills: Like José Saramago (Blindness) or filmmaker M. Night Shyamalan (The Sixth Sense), Mills’ self-imposed mandate to write quirk/twist/etc., has led to some lesser books—if the quirk/twist doesn’t work, you’re shitoutta luck. But I love one other book of Mills’, Explorers of the New Century (2005), which seems at first to be a satire of a boy’s adventure tale, c. 1900, but becomes something else entirely—if I call it allegorical you might not want to read it, but do. It’s a great leap of imagination—in a league, perhaps, with Jonathon Swift. Anyway, Restraint of Beasts [for the record, I have never typed that title without first typing Restraint of Beats] . . . here’s a teaser for it from Goodreads:

Once upon a time in Scotland, there were three men who built high-tension fences, the kind that keep animals in and humans out—or maybe the other way around. Magnus Mills gives us a wiry novel of tensile strength that proves him a writer of ferocious talent. Eerie, resonant, spare yet rich in tones both hilarious and ominous—as if a work by Irvine Welsh, or perhaps Macbeth, had been adapted by the Coen brothers—his story has a finale so ingenious, insidious, and satisfying, it remains locked in the mind long after the last wire has been strung into place.

Ragtime: This one caused a major fuss when it first appeared—that, for instance, real people mingled with invented ones so freely in its pages, that their imagined conversations could be set down as if transcribed. In its way, a revolutionary novel. Down at its heart is the (real-life) murder of architect Stanford White by the husband of actress/model Evelyn Nesbit, Harry Thaw in 1906.

In Cold Blood: Much has been written about Capote’s fascination with killers Dick Hickock and Perry Smith. What concerns us here is his use of a novelist’s tools to tell this true crime story (see Mailer, above). Autofiction and nonfiction novel are familiar terms now, but this intermingling of genres/techniques was radical at the time, another outcome of the counter-cultural upheaval of the Sixties.

New Journalism, as it was called, or “participatory journalism” was another facet of this revolution—where the reporting of the story becomes part of the story, as in George Plympton’s books—Paper Lion (1966) and others—then Tom Wolfe’s books, notably, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968) and the crazed sagas of Hunter S. Thompson, starting with Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971), which spawned the term gonzo journalism. Like Wolfe, Joan Didion was both journalist and novelist. Her principal contribution was her voice—cool, precise, saturated with attitude, as in her 1968 collection, Slouching Towards Bethleham. Even science books began to reflect this shift. By the 1980s, there were works like David Quammen’s Natural Acts: A Sidelong View of Science and Nature (1986) and The Flight of the Iguana (1989), and Tim Cahill’s Jaguars Ripped My Flesh: Adventure Is a Risky Business (1987).

Dreiser: Another book I should’ve read (?), but having slogged through Sister Carrie (1900), I simply could not face another page of Dreiser’s turgid prose, no matter how gripping the story. Anyway, An American Tragedy is based on a famous murder case in upstate New York, the death of Grace Brown in 1906, then the trial and eventual execution of her lover, Chester Gillette.

Flint: This one almost qualifies as “true crime”—much of the real story is retained, and the alterations involve consolidation, shaping, and so on. The real names are used. It’s a good example of how blurry the line between “true crime” and “fiction based on true crime” often is. We like to think there’s an essential (even existential?) distinction between fiction and nonfiction, but in fact the border is porous. We’ve always had what the Frenchies call the roman à clef [novel with a key], the real peeps/events under “thinly veiled” aliases.

Here’s Flint’s website, where she explains her stance on “real” vs. “invention” and other writers she feels akin to.

https://emmaflint.com/little-deaths/

Picoult: Several of the writers in this list are names you know [Picoult, Phillips, Donoghue], but for different books—unless you’re a die-hard fan (Picoult has those, in spades). Nineteen Minutes concerns the aftermath of a school shooting in a small New Hampshire town. The presiding judge’s daughter (as the blurb puts it) should be the state's best witness, but she can't remember what happened before her very own eyes--or can she?

Cline: I could’ve slotted this one in the earlier list. Though a first novel, it got heaps of attention—a testament to good writing, good marketing, good reviews, good word of mouth, and centered on a famous nexus of crimes. The Girls was widely/powerfully praised, appeared on major year-end lists. You might expect anything having to do with the Manson acolytes would feel (way) over-familiar, yet Cline’s angle is new; we see how her character was sucked into that coterie, and how even a near-miss colors the remainder of a life.

Missing Word: Wow, close call! I almost posted today’s post without this one, which turned up just this morning. De Gregorio is an award-winning Italian writer—journalist, novelist, editor, columnist, TV presenter. Thriller, 116 pp., missing kids.

Kent: Iceland, the 1829. Agnes Magnúsdóttir awaits execution for the violent murder of her previous master. Lyrical, deeply researched, atmospheric. Agnes’s partial confession to a young priest completed by her narration to the reader.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/17333319-burial-ritesPhillips: Winner of most recent Pulitzer for Night Watch (2023). On my TBR list. She’s been publishing dependable literary fiction for years—on my radar since her debut collection of stories, Black Tickets (1979). Quiet Dell is based on the 1931 murder, in West Virginia, of a con man by a young widow named Asta Eicher. Phillips grew up nearby—the story was passed down by her mother who was haunted by it.

Hanks: Once in a while, violent crime befalls a writer’s own family. I think of Maggie Nelson’s two powerful short books about the death of her aunt: Jane: A Murder (2005) and The Red Parts: A Memoir (2007). For Hanks, the victim was his mother—disappeared from her workplace in Georgia when he was in eighth grade, her remains found eight years later. This angle makes the novel a uniquely poignant portrait of a family, an era in the American South, and a man’s emotional odyssey.

Dawson: I’m going to stick with my practice of listing these titles by date of first publication, but this one and Jesse’s, A Pin for the Peephole (see below) are about the same murder/trial. A quick overview from The New Yorker [2005]:

In 1922, Edith Thompson, a millinery clerk, and Frederick Bywaters, who worked in a ship's laundry, were arraigned in the Old Bailey for the stabbing death of Edie's loutish husband, Percy—he as the perpetrator and she as co-conspirator. The case was sensational, involving not only adultery and incriminating letters but also a double betrayal (Freddy was the boyfriend of Edie's sister Avis). Many believed that Edie was innocent, indicted on moral but not criminal grounds. Piecing together contemporary news accounts and the gist of Edie's notes to Freddy from Holloway Gaol, Dawson has fashioned an epistolary novel marked by an almost unfaltering grasp of period atmosphere—the trolley ride, the felt cloche—and a consummate knowledge of erotic obsession.

A couple of other links—the first is a Q & A on the novel from Dawson’s website.:

https://jilldawson.co.uk/q-a-on-fred-edie/

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/892331.Fred_Edie

Donaghue: Most readers know her from gripping/claustrophobic novel, Room (2010), but she has more than a dozen others, along with story collections and plays.

Slammerkin: an 18th-century term meaning a loose gown or loose woman.

Publisher’s Weekly: “Donoghue takes scraps of the intriguing true story of Mary Saunders, a servant girl who murdered her mistress in 1763, and fashions from them an intelligent and mesmerizing historical novel. Born to a mother who sews for pennies and a father who died in jail, 14-year-old Mary's hardened existence in London brings to mind the lives of Dickens's child characters.”

Here’s the bit on Slammerkin in a recent LitHub post on real crimes inspiring novels:

Using scant information regarding the life and hanging of a sixteen-year-old maid, Mary Saunders, in the 18th century, Donoghue recreates a vivid story of a young woman whose greed for beautiful things leads her from poverty, to prostitution, to a position in a couple’s household, and ultimately to the noose all within her sixteen years. A colorful romp through the social highs and lows of its setting, beware of where a longing for a red silk ribbon can lead you.

Ellroy: I haven’t read this one, but I can vouch for Ellroy on the basis of American Tabloid (1995). According to Wiki, “Ellroy has become known for a telegrammatic prose style in his most recent work, wherein he frequently omits connecting words and uses only short, staccato sentences . . .” It’s a unique voice—some may find it off-putting, but I ate it up. (Because, as you know, voice is king.)

About the original case:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_DahliaJesse: See the note above on Jill Dawson’s, Fred and Edie (2000).

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/aug/23/a-pin-to-see-peepshow-achingly-human-portraithttps://www.stuckinabook.com/a-pin-to-see-the-peepshow-by-f-tennyson-jesse/

More books to be added to my TBR! Thank you for the storytelling lesson; I really needed that.