[Note: Put cursor over footnote for pop-up.]

Yet Another Year of Big Male Books:

The Day of the Jackal, Frederick Forsyth

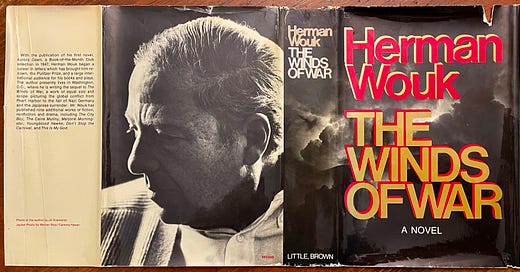

The Winds of War, Herman Wouk

The Exorcist, William Peter Blatty

The New Centurions, Joseph Wambaugh

Honor Thy Father, Gay Talese

Among the Literary Novels of 1971:

Post Office, Charles Bukowski 1

The Book of Daniel, E. L. Doctorow 2

The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, Ernest J. Gaines3

Being There, Jerzy Kosinski 4

Briefing for a Descent Into Hell, Doris Lessing 5

Birds of America, Mary McCarthy 6

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, Elizabeth Taylor 7

Rabbit Redux, John Updike 8

Selected works by World Writers:

Chronicle in Stone, Ismail Kadare [Albania]

August 1914, Alexander Solzhenitsyn [USSR]

Group Portrait with Lady, Heinrich Böll [Germany] 9

I Served the King of England, Bohumil Hrabal [Czech] 10

Malina, Ingeborg Bachmann [Austria] 11

In a Free State, V. S. Naipaul [Trinidad/England] 12

Special Notice:

A Small Grab Bag of Nonfiction:

A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with Don Juan, Carlos Castaneda 15

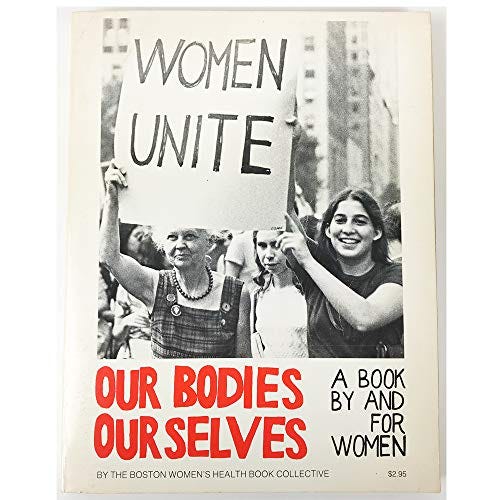

Be Here Now, Ram Dass 16

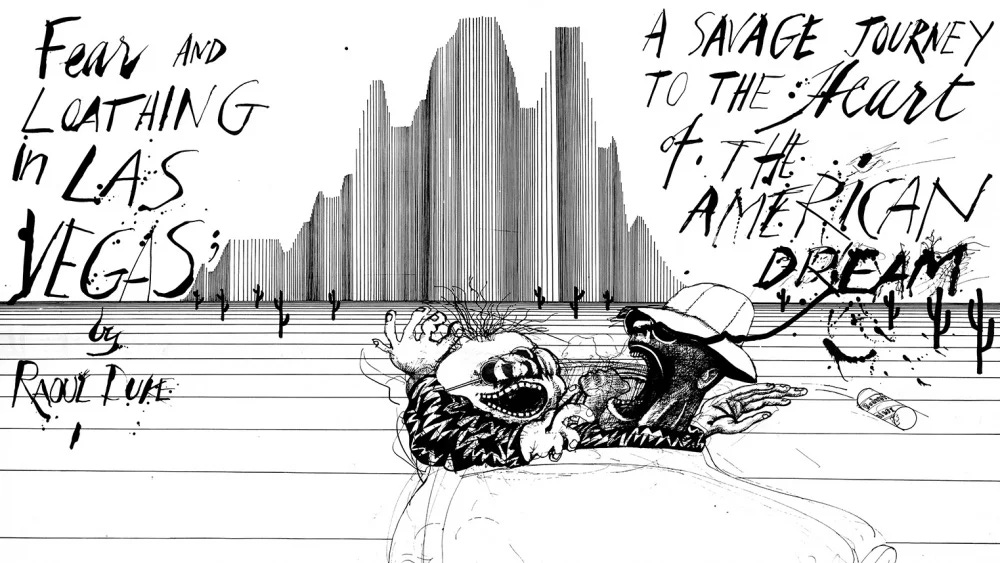

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream, Hunter S. Thompson. 17

Our Bodies, Ourselves, The Boston Women’s Health Collective 18

My List:

Grendel, John Gardner 19

A Guardian Angel Recalls, Willem Frederik Hermans 20

The Lathe of Heaven, Ursula K. Le Guin 21

Lives of Girls and Women, Alice Munro 22

The Complete Stories, Flannery O'Connor (posthumous)

Another Roadside Attraction, Tom Robbins 23

Angle of Repose, Wallace Stegner 24

The Underground Man, Ross Macdonald 25

Bukowski’s first novel. He was a denizen of L.A., a poet of the underclass. According to Wiki: “In December 1969, John Martin founded Black Sparrow Press in order to publish Bukowski's writing, offering him $100 per month for life on condition that Bukowski would quit working for the post office and write full-time for Black Sparrow. Bukowski agreed; three weeks later, he had written Post Office.

Black Sparrow remains an important indie press. There are still scads of Bukowski books in print—titles such as The Days Run Away Like Horses Over the Hills (1969), Love Is a Dog from Hell (1977), The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship (1998 ), What Matters Most Is How You Walk Through the Fire (1999) and a few dozen others. For a while there many young male poets would go through a Bukowski phase, just as many young male fiction writers would go through a Ray Carver phase. Anyway, for the record, you should read some Bukowski.

An early Doctorow novel, loosely based on the story of Julius and Ethel Rosenburg, told by the oldest son. Doctorow’s breakout novel, Ragtime, came four years later, 1975. He went on to be a major figure in American letters.

The bio sketch for Gaines begins:

Gaines was among the fifth generation of his sharecropper family to be born on a plantation in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana. That became the setting and premise for many of his later works. He was the eldest of 12 children, raised by his aunt, who was disabled and had to crawl to get around the house. Although born generations after the end of slavery, Gaines grew up impoverished, living in old slave quarters on a plantation.

The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman became a TV movie starring Cicely Tyson in 1974 (it got a basketful of Emmys). His 1993 novel, A Lesson Before Dying won major awards, but I especially like A Gathering of Old Men (1983)—like Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and Gloria Gaynor’s Bailey’s Cafe, it uses a rotating cast of first-person narrators.

There’s a certain amount of murk surrounding Kozinski’s personal history and some doubt seems to exist regarding the authorship of his works. If you want to follow that trail you can check out the Wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerzy_Kosi%C5%84ski

I haven’t read Being There, but I did read The Painted Bird (1965). It’s the story of a young boy abandoned in Eastern Europe during the Holocaust—a very grim, very tough novel, saturated with cruelty, mercilessness, disease, and abject superstition; if we didn’t know better, we’d think we were adrift in the Dark Ages, or in the darkest of fairy tales. And yet, the writing is sublime. Here’s a sentence about the old woman who has sheltered him:

She looked like an old green-gray puffball, rotten through and waiting for a last gust of wind to blow out the black dry dust from inside.

Lessing was extremely prolific, wrote in every genre, from novels to opera libretti to memoir to poetry, plays, essays, science fiction . . . won dozens of awards (she was the 2007 Nobel Laureate in Literature) and was, in short, a very intimidating figure. Briefing for a Descent into Hell is called a psychological thriller—I haven’t read it, but read one from roughly the same period, The Memoirs of a Survivor (1974), a strange work set in a dystopian near-future.

McCarthy is a complex figure—fiction writer, high-profile critic and social activist. Born in Seattle, orphaned when both parents died in the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1917-18, sub-sequently raised by abusive Irish-Catholic relatives in Minneapolis; atheist, four times married, antiwar protester, winner of awards, honorary degrees, Guggenheims, etc. Her 1963 novel, The Group, spent two years on the New York Times bestseller list.

In the June 18, 2012 issue of The New Yorker, there’s a piece titled “Mary McCarthy, Edmund Wilson, and the Short Story That Ruined a Marriage” [here’s the link but I think only NYer subscribers can access it: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/mary-mccarthy-edmund-wilson-and-the-short-story-that-ruined-a-marriage]. Anyway it contains this illuminating paragraph:

“The Man in The Brooks Brothers Shirt,” published in Partisan Review in 1941—which begins with a young bohemian intellectual setting out to raise the consciousness of a middle-aged businessman encountered in the club car of the train taking her West, only to wake up the following morning, naked and hungover, alongside the man, who looks like “a young pig”—had made her a heroine to a certain kind of young woman. For Alison Lurie, studying at Radcliffe, the story made clear “you could have a relationship with a man just for the fun of it and you didn’t have to feel guilty or upset.” For Pauline Kael, “it was tonic.” This was partly because it offered a heroine who “could be asinine but she wasn’t weak.” For a sixteen-year-old George Plimpton, “that somebody could write a story about things like that” made it remarkable. He added that, at Exeter, the story “made almost as much an impression as Pearl Harbor.”

I have not read Birds of America [and didn’t realize until now that Lorrie Moore’s collection of the same name must be an homage], but it was well-received—“an endlessly fascinating novel of an American student finding his way in 1960s Paris” according to the S. F. Chronicle.

In Birth Year Project 1952, I wrote a note about Virago Modern Classics (Barbara Pym footnote). Elizabeth Taylor (the other one) was another discovery I made via Virago—A Game of Hide and Seek (1951), Sleeping Beauty (1953). Haven’t yet read Mrs. Palfrey . . . but it seems to have a devoted following. Here’s the blurb:

Attentive relatives, especially grandchildren, are the chief currency at the Claremont, a retirement hotel in London. But the proud, recently widowed Mrs Palfrey’s only grandson Desmond has not responded to her numerous invitations to visit. Through an accident in the street she meets Ludo, an insolvent young writer with an indifferent family, and a mutually satisfying arrangement ensues. He pretends to be Desmond, and as she treats him to meals in the Claremont’s dining room, they form a deep and affectionate bond. Yet even harmless, joyful deception must come to an end. This is a darkly funny, unsentimental look at the loneliness of old age and the vicissitudes of human attachment.

Like Alice Munro, John Updike was a major influence on my short story writing. As for his novels: I think he wrote too many, too fast—in general, I like writers who take their time and don’t churn out projects, boom, boom, boom. The Rabbit books are considered his magnum opus—Rabbit Run (1960), Rabbit Redux (1971), Rabbit Is Rich (1980), and Rabbit at Rest (1990), but I’m not fond of this second one. When you stand back and look at the whole sweep of Rabbit’s life you see what a rich portrait it is—rich in observation, small details, pathos . . . the thing is, Rabbit’s robustly endowed with character flaws. As he did in novels like Couples, Updike was keen on capturing the aura of the “sexual revolution.” This isn’t the spot to deal with the big issues in coming to terms with Updike. I think readers should read the whole Rabbit series, and I think Updike was a premier short story craftsman—see the later collections of stories—The Afterlife and Other Stories (1994), My Father’s Tears and Other Stories (2009), as well as The Maples Stories (2009), which aggregates the stories he wrote about one family over the years. Finally, Updike is one of the finest writer of sentences I’ve ever read.

I came to Böll only recently, via Penguin’s reprint of his 1959 novel, Billiards at Half-past Nine, which I loved. I’ve since read The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1974)—Group Portrait . . . is waiting on my TBR shelf. Böll was a pacificst, dedicated to progressive policy, constantly at odds with Germany’s conservative media and the Catholic Church. He was the 1972 Nobel Laureate in Literature.

Hrabel has undergone a great revival in recent years. After the failure of the “Prague Spring” in 1968, Hrabel was unable to publish in Czechoslovakia; many of his works circulated by way of samizdat. This novel and Too Loud A Solitude (1977) are his best known works in English, along with the powerful Closely Watched Trains (1965)—Hrabel worked closely with director Jiří Menzel on the film version, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film in 1968.

Another writer I’d never heard of, but the effusive reader reactions have me putting Malina on the TBR shelf. The New York Times Book Review: "Enigmatic, yet piercing: equal to the best of Virginia Woolf and Samuel Beckett."

My first Naipaul was A Bend in the River (1979), which I recommend. In a Free State won the Booker in 1971; Naipaul won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001. [There’s a longer note on Naipaul under A House for Mr. Biswas in Birth Year Project: 1961.]

Forster was a highly regarded public figure in England, known primarily for A Room with a View (1908), Howard's End (1910), and A Passage to India (1924). He wrote Maurice, a gay love story, in 1914, but it remained unpublished until after his death.

Lovers of The Bell Jar may be surprised to see it here in 1971 (I listed it under 1963 in the Birth Year Project). The publication history turns out to be more complex than I knew. This was Plath’s only novel [she was a young poet with a dedicated following—The Colossus and Other Poems (1960)]]. The Bell Jar mirrors Plath’s own struggle with depression; the 1963 edition bore the pen name Victoria Lucas. Plath died by suicide just a month after its publication in England, where she lived with her husband, the poet Ted Hughes. The first edition under her own name came in 1967 (in the U.K), but the first American edition was delayed until 1971 according to the wishes of Hughes and her mother. Her posthumous collection of poems, Ariel, was hugely popular, especially among young women poets, and is a cult classic. After her death, there was an ongoing feminist backlash against the role of Hughes in her life—way too ornate an issue to tackle here.

From Wiki:

“Starting in 1968, Castaneda published a series of books that describe a training in shamanism that he received under the tutelage of a Yaqui "Man of Knowledge" named don Juan Matus. While Castaneda's work was accepted as factual by many when the books were first published, the training he described is now generally considered to be fictional. Scholars have debated "whether Castaneda actually served as an apprentice to the alleged Yaqui sorcerer don Juan Matus or if he invented the whole odyssey." Castaneda's books are classified as non-fiction by their publisher, although there is consensus among critics that they are largely, if not completely, fictional."

I was a 20-year-old college student in 1968, and can report that we ate this stuff up. Try the first one, The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge (1968)—try putting it down.

Richard Alpert and Timothy Leary were colleagues at Harvard in the early 1960s. They underwent some consciousness altering/raising, Timothy Leary becoming, well, Timothy Leary, and Alpert becoming Ram Dass. If you were a counterculture warrior/seeker in those days, you had a copy of Be Here Now. While Leary was off doing his Leary thing, Ram Dass became a key figure in teaching Eastern Spirituality, yoga, to the West. He led a fascinating life. Read more about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ram_Dass

And read Be Here Now.

The epitome of “gonzo journalism”—way to the far side of the emerging genre of reportage known as New Journalism, in which the drama of the journalist getting the story becomes an integral part of the story. Another great example is The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe (1968). In the case of Thompson, a core of fact is embedded in high-octane/hyperbolic prose. As one commentator put it:

The story follows its protagonist, Raoul Duke, and his attorney, Doctor Gonzo, as they descend on Las Vegas to chase the American Dream through a drug-induced haze, all the while ruminating on the failure of the 1960s countercultural movement. The work is Thompson's most famous book, and is noted for its lurid descriptions of illicit drug use and its early retrospective on the culture of the 1960s.

It appeared first in Rolling Stone, unforgettably illustrated by Ralph Steadman.

Beowulf from the monster’s POV.

Gardner’s other novels include, The Sunlight Dialogues (1972) and October Light (1976). He was also an influential essayist [On Moral Fiction (1978)] and writing teacher [The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers (1984)]. He died in a motorcycle crash at the age of 49.

Hermans was a prolific and highly respected Dutch writer . . . and I’d never heard of him until, as a subscriber to Archipelago Books, A Guardian Angel Recalls came in the mail. This is a very dark comedy set in the days just before Germany’s invasion of the Netherlands. It’s narrated by the long-suffering angel tasked with watching over a flawed public prosecutor named Alberegt. Speeding back to the city after putting his Jewish lover on a ship for America, Alberegt runs over a young girl on a lonely stretch of road, hides her body in the weeds, and goes on. “Throughout this extraordinary novel all the characters are shown to be at the mercy of conflicting impulses, of which the guardian angel’s admon-tions are but one. Their helplessness is their pathos and their disgrace," wrote Tim Parks in The New York Review of Books. In the New York Times, Alida Becker said, “Repellent as Alberegt can be, his predicament is wickedly enticing."

Science fiction novel (duh) set in a near-future (now the near-past) Portland, OR, now aswarm with three million residents. The main character’s dreams can alter past and present reality. It was her eighth novel [sixty more books of all sorts followed]. She was chagrined to discover that the quote she’d based the title on (by the ancient Chinese philosopher, Chuang Tzu) had been mistranslated—there were no lathes in China until centuries later. A better version:

To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the scourge [or whip] of heaven.

This is Munro’s only novel. She became recognized as the premier short story writer of her generation (she won the Nobel Prize in 2013, Canada’s only woman laureate in Literature). Her stories are often long, always richly articulated, sometimes segmented—hence, reading this novel is little different than reading the stories. Years ago, when I first read her work, the details of lived life were so pervasive I assumed she was mining her own life, and no doubt she was. But by the time I’d logged dozens of them, I came to see how much of had to be invention. She remains a hero of mine.

I remember reading this in the Landcruiser as we drove West after college (the eight-track tape player playing “Down By the River” and “Cinnamon Girl”). Robbins had a loosey-goosey counterculture vibe. I hung in there for the next couple, Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (1976) and Still Life with Woodpecker (1980), but gradually lost interest. Be that as it may, Robbins has a dedicated readership and Robbins has accrued all sort of honors; he’s also long been involved in cultural and social affairs around Seattle.

This is a fine novel, winner of the 1972 Pulitzer for Fiction. Stegner was a highly influential figure in the literature of the American West—as novelist, critic, and teacher. Read about him: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wallace_Stegner

In the years after the publication of Angle of Repose a significant controversy arose over Stegner’s use of his source material, the reminiscences of Mary Hallock Foote. It’s a complicated story—you can get a taste of it here:

I used to read mysteries now and then—went through Raymond Chandler’s and other classics. In the 70s, I read both John D. MacDonald and Ross Macdonald. John D.’s character was Travis McGee, Ross’s was Lew Archer. John D. MacDonald’s titles always had a color in them, and, I think, sold better than Ross’s, but Ross was a better writer (critic John Leonard once wrote that Macdonald had “surpassed the limits of crime fiction and become a major American novelist”).

There’s an odd footnote to the Macdonald/MacDonald confusion. Ross was born Kenneth Millar (pronounced Miller). When his wife Margaret began to have some success as a mystery writer, under the name Margaret Millar, Kenneth Millar constructed a pen name to avoid any mix-up with her; using a mash-up of family members’ names, he became Ross Macdonald. Then along came John D. MacDonald. Oh well. Ross’s books were usually set in the Santa Barbara, CA, environs. I haven’t read The Underground Man in years, but I remember that it was my fave.