Birth Year Project:

You supply your birth year, I respond with a short list of books published that year—the popular/well-known titles first, then some books I'd recommend. If your year's already been done, I'll do an update. So far, we’ve done 17 years altogether, between 1944 and 1989.

Extra credit: You read one of the books (ideally one you're unfamiliar with), then tell me what you thought. If we get enough of these, I'll aggregate and post.

Well-Known/Popular Books:

To Sir, With Love, E.R. Braithwaite1

Advise and Consent: A Novel of Washington Politics, Allen Drury2

Goldfinger, Ian Fleming3

Mrs. 'Arris Goes to Paris, Paul Gallico

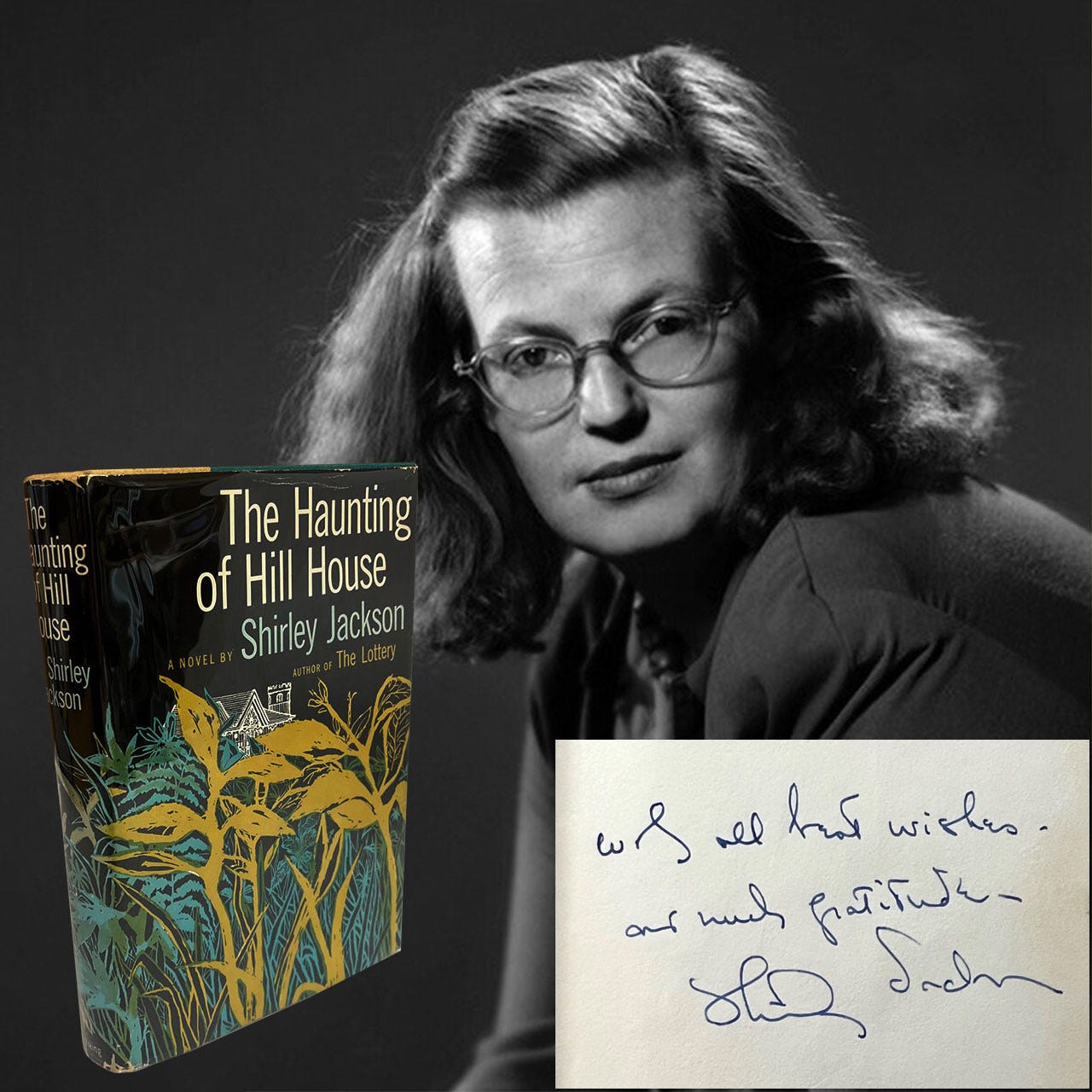

The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson4

A Separate Peace, John Knowles

Hawaii, James A. Michener

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, Mordecai Richler

Five Literary Novels/Collections:

Naked Lunch, William Burroughs (1959)5

Advertisements for Myself, Norman Mailer6

Goodbye, Columbus, Philip Roth7

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, Alan Sillitoe8

Henderson the Rain King, Saul Bellow

Four Classic Genre Novels:

A Canticle for Leibowitz, Walter M. Miller Jr.

Starship Troopers, Robert A. Heinlein

The Sirens of Titan, Kurt Vonnegut 9

Titus Alone, Mervyn Peake 10

Novels That Became Films of the Same Title:

Psycho, Robert Bloch

The Manchurian Candidate, Richard Condon

The Longest Day, Cornelius Ryan

The Magic Christian, Terry Southern

The Hustler, Walter Tevis11

Four Works of World Literature:

A Monkey in Winter, Antoine Blondin12

Billiards at Half-Past Nine, Heinrich Böll 13

The Tin Drum, Günter Grass14

Life and Fate, Vasily Grossman15

Special Mention:

James Joyce [biography], Richard Ellmann16

Lady Chatterley’s Lover, D. H. Lawrence 17

The Status Seekers [social commentary], Vance Packard18

The Elements of Style, William Strunk Jr. and E. B. White19

My List:

Mrs. Bridge, Evan S. Connell 20

Mountolive, Lawrence Durrell 21

“The Last Running” [short story], John Graves 22

The Galton Case, Ross Macdonald 23

Zazie in the Metro, Raymond Queneau 24

Billy Liar, Keith Waterhouse 25

To Sir: Well-known title: iconic British film of the mid-60s starring Sidney Poitier, song by Lulu on the radio . . . but few people would recognize the novelist’s name. Braithwaite was born in Guyana to British parents (both had gone to Oxford). Despite his degree in physics, he reluctantly took a teaching job in the East End of London when he could find no work in his field. He continued to write on racial discrimination, social work, was a consultant and lecturer for UNESCO, served as Guyana’s Ambassador to Venezuela, later taught in the States. He died in 2016 at the age of 104.

Drury: Over one hundred weeks on the NYT bestseller list, awarded the 1960 Pulitzer in Fiction.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advise_and_Consent

Goldfinger: I have nothing fresh to say about Bond No. 7, but I thought you might like this: Rick Beato’s cool drill-down on the theme music.

Haunting:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Haunting_of_Hill_House

Interest in Jackson’s work seems to wax and wane—at the moment it seems to be on the upsurge, due in part to the 2018 Netflix series based (loosely) on this novel, as well as Elizabeth Hand’s sequel, A Haunting on the Hill (2023).

I used to take it for granted that everyone knew “The Lottery” (first published in The New Yorker in 1948), her classic story about group psychology, scapegoating, ritualized evil, with its echoes of New England’s Puritan past . . . but I’m not so sure anymore. Here’s a Wiki on it, but if you don’t know the story, read it first, OK?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_LotteryNaked:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naked_Lunch

Mailer: Pugnacious, wildly talented writer of novels and short stories, reportage, nonfiction, and hard-to-categorize other stuff . . . a boozer, public figure, candidate for New York City mayor, married six times, etc. etc. Advertisements, as the title says, is buffet of Mailer matter. I can’t do any kind of justice to his output in this small space . . . he did a book on Marilyn, a book on the moon race, a book on the the 1967 anti-Vietnam March on the Pentagon, a mammoth novel set in Ancient Egypt, another—a “nonfiction novel”—on the crimes and death of Gary Gilmore [The Executioner’s Song (1979)] etc. etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norman_Mailer#cite_ref-1Oh, and this one:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stabbing_of_Adele_Morales_by_Norman_MailerRoth: A novella and stories, the first of Roth’s 27 works of fiction, winner of the National Book Award. Like John Updike, a terrific writer on the micro level, though a handful of the projects were ill-considered. My favorite is The Plot Against America (2004), an alternate history of the 1940 election—Charles Lindbergh, isolationist, openly anti-semitic, wins the Presidency. Toward the end of his writing life, Roth published a string of powerful short novels: Everyman (2006), Indignation (2008), The Humbling (2009), Nemesis (2010).

Sillitoe: One of the post-war British, especially working-class, novelists/playwrights called the Angry Young Men (others: Kingsley Amis, John Brain, John Osborne, John Wain). Sillitoe was a poet, essayist, playwright, memoirist, writer of children’s books. This novel, about a borstal boy, and his first, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958), are his best known among his many works.

Vonnegut: His second novel, comic sci-fi. Vonnegut before he was Vonnegut—or Vonnegut just before he was called up to the bigs. His first was Player Piano (1952), his third Mother Night (1962).

It was the fourth that gave him the call-up, Cat’s Cradle (1963): Mordant satire, The Book of Bokonon, Ice-nine, “Nice, nice, very nice.” Lots of made-up terms, one of which has been useful to me over the years: the granfaloon. First you have to know what a karass is: “a group of people linked in a cosmically significant manner, even when superficial linkages are not evident.” A granfaloon is a false karass: “a group of who affect a shared identity or purpose, but whose mutual association is meaningless.” Vonnegut’s example: Hoosiers. This has always seemed hilarious to me. Finding other examples in one’s daily life is like shooting fish in a barrel.

Peake: Third of the Gormenghast fantasy novels, not the strongest, but it would be a shame if you missed the first book of the trilogy, Titus Groan (1946), a quirky masterpiece in the Narnia/Harry Potter/Tolkien vein. Its world is non-tangential with ours, vaguely medieval, peopled by a cast of sharply drawn figures. It’s a difficult series to describe—have a listen to Sean from Travel Through Stories,below. And here’s Peake’s Wiki:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mervyn_PeakeTevis: This was Tevis’s first novel, the story of pool hustler “Fast Eddie” Felson challenging the legendary Minnesota Fats, but the book was overshadowed by the 1961 film with Paul Newman and Jackie Gleason. His second novel, The Man Who Fell to Earth (1963) was science fiction, which Nicholas Roeg filmed in the mid-70s (David Bowie starred). Tevis was a heavy drinker/smoker/gambler (he died at fifty-six of lung cancer). He managed to produce six novels and a collection of stories. I got the feeling that he was lucky to have gotten that much finished. A few years ago, I read his novels Mockingbird (1980) and The Queen’s Gambit (1983)—obscure, almost-forgotten books, I thought. Then, suddenly, Netflix made a high-profile miniseries of the latter (with a riveting performance by Anya Taylor-Joy) and it was gratifying to see Tevis’s name in the public eye again.

Monkey: Blondin was mainly a journalist/sportswriter, a hard-drinking bon-vivant type, but to judge from French readers’ comments, this novel shouldn’t be forgotten. The film version (1962) starred heart throb/bad boy, Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Böll: One of the 20th century’s literary giants, Nobel Laureate in 1972. This novel takes place in a single day in 1958, Cologne. A collection of narrators—eleven in all—assemble an account of middle-class Germans’ involvement with the Nazis, centering on father and son, architects, and the destruction of an historic abbey. I’ve read a couple of other Bölls—this one’s my favorite.

Tin Drum: Another Nobel Laureate (1999). This is the first book in Grass’s Danzig Trilogy— followed by Cat and Mouse (1961) and Dog Years (1963), considered “a key text in European magical realism.” Grass was also a poet, playwright, illustrator, and sculptor. Late in life there arose a controversy about his activity during the war—too nuanced to unfold here. Throughout his writing life, he was a harsh critic of Germans who failed to face up to the country’s Nazi past.

Grossman: Re-issued by NYRB:

https://www.nyrb.com/products/life-and-fateJoyce: This was the first big biography of a writer I read—must’ve been in the early 70s. It won the 1960 National Book Award. A classic, among the premier literary biographies. It felt like getting an intimate look behind the curtain. [A revised edition was issued in 1982.]

Chatterley: First published, privately, in Italy (1928) and a year later in France. From Wiki: “An unexpurgated edition was not published openly in the United Kingdom until 1960, when it was the subject of a watershed obscenity trial against the publisher . . . which won the case and quickly sold three million copies.”

This year, 1959, marks the publication of the first unexpurgated edition in the U.S., “after one of the most spectacular legal battles in publishing history.”

Status: Packard was a journalist who became a strong social critic of America’s postwar consumer society. His books The Hidden Persuaders (1957) and The Waste Makers (1960) took on Madison Avenue and planned obsolescence, respectively. Popular sociology books emerged throughout the decade: The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character (David Reisman and others, 1950), The Power Elite (C. Wright Mills, (1956), The Organization Man (William H. Whyte, 1956), to name a few.

Style: If you’re a writer you know this jewel. If you’re interested in its history, you can read about it via the link below. This E. B. White was the same one who wrote Charlotte’s Web (1952) and Stuart Little (1945), who was a premier essayist [in my late 20s, I schooled myself on The Essays of E.B. White (1977), and came to cherish one called “Once More to the Lake”; it depicted his stepson as a boy—he’d grow up to be a New Yorker editor, like White, and though I had not the least inkling of it at the time, he, the stepson, Roger Angell, would play a pivotal role in my life].

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Elements_of_StyleConnell: Birth Year Project: 1969 included Mr. Bridge, the companion volume to Mrs. Bridge. Here’s part of what I wrote then:

Many readers know Connell only from his nonfiction work, Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Bighorn (1985), but these two novels were groundbreaking in their way—an upper middle-class Kansas City family, between the two world wars, told in very short, vignette-like chapters. Quite moving in their way, both of them.

That doesn’t explain why some readers are so fond of these books, especially the first. The terse chapters have a deadpan quality, hovering between comedy and pathos. Each is titled: No Scenes in Church, Grace Barron, Sex Education, Frayed Cuffs, Who Can Find the Caspian Sea? Tobacco Road, Marmalade, Change of Itinerary . . . There’s no authorial telling you what to think here—it’s like being given a stack of Polaroids, all very ordinary-looking, yet somehow suggesting that matters of great consequence lie just below their surface.

Mountolive: This is the third book in Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet, following Justine (1957) and Balthazar (1958), and preceding Clea (1960).

Here’s Jan Morris’s note on re-reading the Quartet, published in The Guardian in 2012:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/feb/24/alexandria-quartet-lawrence-durrell-rereadingI’d bounced off Justine several times before reading the Quartet straight through in my forties. As Morris says, it’s way over-written—if that’s a deal-breaker for you, then read something else. Ordinarily it would be for me, but Durrell won me over—I loved being in that world. An English writer, Darly, narrates Justine; at the start of Balthazar, a boat approaches an island in the Mediterranean where Darly and the young daughter of his courtesan girlfriend have taken refuge; on the boat is Balthazar who has read the text of the first book and now tells Darly he hasn’t fully understood Justine’s story and wants to give him the missing pieces—thus, Balthazar is Justine corrected, deepened. David Mountolive, the English ambassador to Alexandria is the center of the third book, the only one rendered in third-person. There are passages of stunning beauty, a night fishing scene in particular. Here’s another little taste:

He slipped lightly downstairs into the dusky street, counting his money and smiling. It was the best hour of the day in Alexandria—the streets turning slowly to the metallic blue of carbon paper but still giving off the heat of the sun. Not all the lights were on in the town, and the large mauve parcels of dusk moved here and there, blurring the outlines of everything, repainting the hard outlines of buildings and human beings in smoke.

“The Last Running”: A short story I revere. Texas in the 1920s. Two old foes. One buffalo named Shakespeare.

Ross Macdonald: I’m listing this detective novel (which I haven’t read) because you should know Macdonald—it’s said to mark the beginning of his best writing. My own fave is The Underground Man (1971), sixteenth of his Lew Archer novels.

Side note: Macdonald was Canadian; his real name was Kenneth Millar. He adopted the pen name (a mash-up of ancestors’ names) to keep readers from conflating his work with that of his wife, Margaret, a mystery writer herself. Soon, though (in the No-Good-Deed-Goes-Unpunished Department) writer John D. MacDonald began publishing his popular series of Travis McGee novels.

Zazie: A small gem. Here’s a blurb from Amazon:

Impish, foul-mouthed Zazie arrives in Paris from the country to stay with Gabriel, her female-impersonator uncle. All she really wants to do is ride the metro, but finding it shut because of a strike, Zazie looks for other means of amusement and is soon caught up in a comic adventure that becomes wilder and more manic by the minute. In 1960 Queneau's cult classic was made into a hugely successful film by Louis Malle. Packed full of word play and phonetic games, Zazie in the Metro remains as stylish and witty as ever.

Waterhouse: Found this classic of the Young-Man-Behaving-Badly genre, while checking out Valancourt books, publishers of nearly forgotten LGBTQ, horror, occult, Gothic, etc, novels. This book is a hoot (un-PC).

https://www.valancourtbooks.com/billy-liar-1959.html